document

advertisement

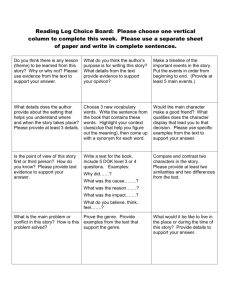

Lecture 10: Blaxploitation, Race and Genre in the 1970s Shaft (1971) Directed by Gordon Parks Professor Michael Green 1 Previous Lecture • Racial Projects and Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner • Sidney Poitier and Supertoms • Interracial Buddy Films and The Defiant Ones • Writing About Film 2 This Lecture • Race and Genre Anxiety in the 1970s • Blaxploitation: Setting the Context • Blaxploitation as Genre • Writing About Film: Using Sources I 3 Race and Genre Anxiety in the 1970s Dirty Harry (1971) Directed by Don Siegel Lecture 10: Part I 4 The Purpose and Function of Genre • Genre conventions encourage repetition, reconfiguration and renewal of familiar cinematic forms – war movie, western, sci-fi, melodrama – to appeal to audiences who take pleasure in their familiarity. • Genres are used by Hollywood as a convenient way to predict ticket sales, but they are also ideological in the way that their conventions reflect and reify such subjects as race, class, gender and sexuality. 5 Genre Reflects Society • In their sameness from era to era, genre conventions – such as gunfights and horse riding in the Western – often contribute to an ahistorical view of the world. • However, alternations in these conventions also signify the historical moment in which the film is made, sometimes reflecting broad structural and social changes. • “Revisionist” Westerns of the late 1960s and early 1970s – The Wild Bunch, McCabe and Mrs. Miller – are a good example. 6 Race in Genre Representation “Race plays a crucial role in generic representations. Hollywood westerns, war movies, detective stories, melodramas, and action-adventure films often rely on racial imagery, underscoring the heroism of white males by depicting them as defenders of women and children against predatory ‘Indians,’ Asians, Mexicans, and black people . . . they move toward narrative and ideological closure by restoring the white hero to his ‘rightful’ place.” – George Lipsitz, “Genre Anxiety and Racial Representation” Genre in the 1970s • Lipsitz argues that the blockbusters of the 1970s – such films as The Godfather (1972) Jaws (1975) and Star Wars (1977) – relied upon familiar genre conventions to affirm continuity and uphold conservative ideology and white patriarchy in an era of drastic social change. • However, these blockbusters followed an era of “genre anxiety” in which genre films more overtly represented the social and cultural anxiety of the era. 8 “Genre Anxiety” “The racial crises of the 1960s in the U.S. gave rise to “genre anxiety,” to changes in generic forms effected by adding unconventional racial elements to conventional genre films. The emergence of those films, their eclipse later in the 1970s by changes in Hollywood’s marketing and production strategies . . . can best be understood not as aesthetic changes alone but as a register of dynamic changes in social relations.” – George Lipsitz, “Genre Anxiety and Racial Representation in 1970s Cinema” Race and Genre in the 1970s • Many genre films from the era showed racial concerns as well, including the detective film Cotton Comes to Harlem (1970); the Westerns Buck and The Preacher (1971) and Blazing Saddles (1974); action films such as Gordon’s War (1973) and comedies such as Car Wash (1975) and A Piece of the Action (1977). 10 Case Study: Blacula • Blacula (1972) used the genres of horror and vampire movies to reflect the racial tensions of the era and to advocate for racial and social equality. • Lipsitz argues that the movie presents “a playful mix of the familiar and the unfamiliar . . . by inserting contemporary social concerns into a familiar genre.” Pause the lecture and watch the clip from Blacula. 11 Reinforcing Genre Conventions • As some films from the era subverted genre conventions to reflect and advocate for social change, other films strengthened and reinforced genre conventions as a way of upholding conservative values. Pause the lecture and watch the clip from Dirty Harry. Race and Phallic Symbols • • Black men have been associated with phallic symbols, suggesting, from a Freudian perspective, the anxiety white society has typically had about black male sexuality and, to be blunt, size. In the south, during the days of lynching, black men would often be castrated. In films, they're typically killed first and usually by a phallic symbol like a sword, a gun, a spike, etc. Examples in Film • • Hence, the connection between stereotypes of black man as sexual threats and the use of phallic symbols in film. Examples include Dirty Harry, Conan the Barbarian (1982); Live and Let Die (1972). Conan the Barbarian (1982) Directed by John Milius Upholding Patriarchal Power “Crime films of the early 1970s, including Don Siegel’s Dirty Harry, reflected “white anxiety” about the black self-activity and subjectivity of the 1960s as well as about economic stagnation by reconfiguring the genre to present authoritarian white male heroes as the only remedy for a disintegrating society . . [in Dirty Harry] criminals and civil libertarians of both genders are coded as “female” forces undermining patriarchal power.” – George Lipsitz, “Genre Anxiety and Racial Representation in 1970s Cinema” Summary of Points • Genre conventions appeal to audiences who take pleasure in their ahistorical familiarity. • But genres are also ideological, often reflecting broad social changes. • Race and gender play a crucial role in genre representation. • In the late 1960s and early 1970s, some genre films reflected and advocated for social change while others reinforced genre conventions and as a way to reinforce social and cultural conventions. 16 Author’s Final Point “The directors of these 1970s films had different agendas, ideologies, and interests. None of them intended either a purely ideological statement or a selfconscious innovation in genre form . . . Whether acknowledged overtly or covertly, the social crises of the early 1970s suffused these films with an instability that posed serious challenges to traditional genre conventions.” – George Lipsitz, “Genre Anxiety and Racial Representation in 1970s Cinema” Blaxploitation: Setting the Context Foxy Brown (1974) Directed by Jack Hill Lecture 10: Part II 18 Sidney Poitier • Poitier was the leading black male actor in America in the 1960s – and virtually the only one. • He symbolized in Hollywood films of the 1950s and 1960s the rising young American black man. • Poitier was the key to the commercial success of Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner because he was well recognized and acceptable to the white audience. 19 Rejecting Sidney Poitier • However, by 1967 and the triple success of Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, To Sir with Love and In the Heat of the Night, black audiences began to reject the kinds of characters played by Sidney Poitier and the racial social problem films he appeared in. • Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner in particular was harshly criticized by black and white critics for its shallowness, its liberal piety and lack of realism. 20 New Representation • New representations of African Americans began to depict them as more masculine; they were not always suppressing their physicality or emotion in deference to threatened white audiences. • In contrast to Poitier, these heroes were often physical, militant and/or politicized. – Jim Brown in The Dirty Dozen (1967) – Woody Strode in Che (1969) – Fred Williamson in M*A*S*H (1970) 21 Industry Trouble • From 1967 – 1976, studios, distressed by their dwindling profits and fading audience, turned over the keys of the kingdom to “the movie brats” a generation of young directors who had been – Film school graduates – Influenced by European art films – Profoundly affected by contemporary history • They made a number of films aimed at younger audiences that embraced social realism and tough, complex themes. 22 The New Hollywood • • • Among the most popular of these films were Dennis Hopper’s Easy Rider (1969) and Robert Altman’s M*A*SH (1970). Other seminal films of the period include Bonnie and Clyde, The Wild Bunch, The Graduate, Five Easy Pieces, Chinatown, Midnight Cowboy and Mean Streets. These films were informed by the concerns of an era, as well as the end of the Production Code in 1968. 23 New Black Films • During this time of Hollywood financial struggle, doors opened for a few African American directors as well, including: – – – • Gordon Parks – The Learning Tree, 1969 Ossie Davis – Cotton Comes to Harlem, 1970 Melvin van Peebles – Watermelon Man, 1970 These films and a few others like them subverted traditional Hollywood representations of blackness. 24 An Honest Depiction • • • These directors were rejecting not only the sanitized, desexualized black figure presented by Poitier, but also the more masculine figures played by Brown and Williamson, who they felt were still subjugated in white narratives. The wanted to see an honest depiction of blacks, a black POV and a black worldview. Some of these films were financially successful, opening the door for more. 25 Blaxploitation as Genre Blacula (1972) Directed by William Crain Lecture 10: Part III 26 What is Blaxploitation? • Blaxploitation: A genre of American film of the 1970s – 50 or so were made, on limited budgets – featuring largely AfricanAmerican casts and with African American actors in lead roles. • The movies were usually action-adventures set in the urban ghetto. • They featured violence and sexualized black characters and situations – a departure from previous black-themed films. 27 Ramping up Production • Desperate over their financial downturn, Hollywood upped production of blackthemed films from 6 in 1969 to 18 in 1972. • Hollywood’s shift towards a more black-oriented product created the boom of the Blaxploitation genre. 28 Sweet Sweetback . . . • Political and economic conditions in 1971 made possible Melvin Van Peebles Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song which became a big hit and launched the genre. • Sweet Sweetback was an independent film that Van Peebles brilliantly marketed. • The movie, once controversial, tells the story of a black man who challenges the oppressive white establishment, a template that other Blaxploitation films would follow. Pause the lecture and watch the clip from Sweet Sweetback. 29 Shaft • Sweet Sweetback was followed a few months later in 1971 by Gordon Parks’ Shaft. • The movie was originally written for a white actor, but with the popularity of Sweetback and the formula it innovated, along with Hollywood’s desire to woo black audiences, the protagonist was changed to black. • The movie was hugely successful and spawned an Oscar winning soundtrack by Issac Hayes. Pause the lecture and watch the clip from Shaft. 30 A Flood of Productions “After Shaft in 1971, there came a flood of productions, extending through 1974, that while they crudely tried to emulate the success of Shaft and Sweetback, repeated, filled in, or exaggerated the ingredients of the Blaxploitation formula, which usually consisted of a pimp, gangster, or their baleful female counterparts, violently acting out a revenge or retribution motif against corrupt whites in the romanticized confines of the ghetto or inner city.” – Ed Guerrero, “The Rise and Fall of Blaxploitation” 31 Energy and Style “These elements were fortified with liberal doses of gratuitous sex and drugs and the representation of whites as the very inscription of evil. And all this was rendered in the alluring visuals and aggrandized sartorial fashions of the black underworld and to the accompaniment of black musical scores that were usually of better quality than the films they energized.” – Ed Guerrero, “The Rise and Fall of Blaxploitation” 32 Examples from the Genre • The 50 or so Blaxploitation films included: – Black Jesus (1971) – Superfly (1972) – Blacula (1972) – Cleopatra Jones (1973) – Gordon’s War (1973) – Foxy Brown (1974) Pause the lecture and watch the clip from Superfly 33 Social Features “Where white suburban America saw violence and destruction, black audiences saw resistance to the specific wrongs of the inner city, which included disenfranchisement, poverty, decay and police brutality. The films were accused of being one-dimensional and needlessly violent by many reviewers, yet they addressed a facet of their audience’s experience, even to the extent of quoting imagery similar to that seen on TV.” – Paula Massood, “Black City Cinema: African American Urban Experiences in Film” Business as Usual • While African-American filmmakers were substantially involved in making early movies in this genre, their participation in subsequent productions was minimal. • Dominant Hollywood – white and male – flush again from the success of the counterculture films, began to control production. 35 The Fate of the Genre • Hollywood had abandoned Blaxploitation and other counterculture films by the mid-1970s. • Out of its fiscal crisis, the studios returned to the conservative filmmaking they had engaged in since the silent era. • Black critics and intellectuals also contributed to the demise of Blaxploitation, complaining about the negative representation of blacks. • By the end of the decade, only one black star existed in Hollywood: Richard Pryor. 36 Writing About Film: Using Sources I Superfly (1972) Directed by Gordon Parks Jr. Lecture 10: Part IV 37 Summary: Tips and Suggestions I • Whenever you critically engage specific topics and terms, you must provide definition and context. • In critical film writing, understand the difference between plot and representation. • Every section in your paper must reiterate your thesis. • Keep it to one topic per paragraph. • Stick to the film to be analyzed. 38 Summary: Tips and Suggestions II • Do not include more than a few lines of plot summary in your paper. • In a critical paper, don’t include opinionated language. In other words, no evaluations! • The revision process is fundamental to the writing process. It is most crucially about streamlining and enhancing ideas and arguments to make them strong, clear, organized, convincing. • Get help! 39 Using Sources as Support • Sources should only support your argument; always proceed your own voice and thesis. • Use sources to – Contribute to your thesis by supporting your argument point – Provide context or background for your topic. – Offering a counterargument for you to refute. 40 Use Sources Judiciously • Do not use sources to speak for you! • Do not use quotations that repeat your points. • Avoid quoting more than is needed. • Brief quotations are generally more to the point than long passages, as too many lengthy quotations weaken the flow of your argument and muddle your voice. • Integrate research into your argument; don’t let it stand for your argument. 41 Integrate and Explain • Introduce direct quotations with your own words, which explain to your reader how to understand or interpret the quotation. • After quoting, explain the significance of quotations; never end a paragraph or section with a quote. • Use direct quotations only when the author's wording is necessary for your analysis or particularly effective. 42 Example “In The Devil Finds Work, James Baldwin argues that The Birth of a Nation “cannot be called dishonest; it has the Niagara force of an obsession.” 5 The obsessive force of The Birth of a Nation comes as a logical consequence of its function as film legitimating the “common sense” of white supremacy.” 6 – George Lipsitz, “Genre Anxiety and Racial Representation in 1970s Cinema” 43 Be True to the Original • End citation alone is not sufficient for direct quotations; place all direct quotations within quotation marks, as in the previous example. • Be sure to copy quotations exactly as they appear, using ellipsis to omit words or sections, and brackets for modifications to grammar. • “None of [the directors] intended either a purely ideological statement or a selfconscious innovation in genre form . . .” 44 Get Help! • Uses sources takes practice and it can sometimes be confusing so get help when you need it. • Review your discipline's main professional reference material on writing – MLA, Chicago, APA – among other. • Ask your professors and instructors. • Use the library support staff! They know this stuff very well. 45 End of Lecture 10 Next Lecture: Laughing Mad about Black Masculinity 46