Chapter 13: Aggregate Supply and Aggregate Demand

advertisement

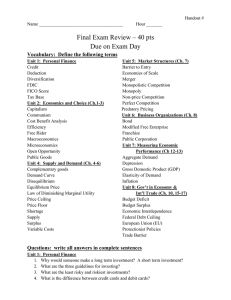

CHAPTER 13 Aggregate Demand and Aggregate Supply Prepared by: Jamal Husein © 2005 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Survey of Economics, 2/e O’Sullivan & Sheffrin Economic Fluctuations Economic fluctuations are irregular, recurring movements of GDP away from potential output, also called business cycles. Aggregate supply and aggregate demand curves are tools of analysis used for understanding key aspects of economic fluctuations in both the short run and the long run. © 2005 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Survey of Economics, 2/e O’Sullivan & Sheffrin 2 Economic Fluctuations The short run in macroeconomics refers to a period of time during which prices change very little, or do not adjust fully to changes in demand. The idea that demand determines output in the short-run will be examined. In the long-run, underlying economic forces push the economy back towards full employment. The level of output in the economy when it operates at full employment is called Potential output. © 2005 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Survey of Economics, 2/e O’Sullivan & Sheffrin 3 Economic Fluctuations A recession is a period when real GDP falls for two consecutive quarters. It starts at the peak of an increase in output, and ends at a trough. A depression is a prolonged period of decline in output, or a severe recession. During the Great Depression, 1929 through 1933, real GDP fell by over 33%, and unemployment rose to 25%. In the U.S., there were 20 recessions prior to World War II, including two severe episodes in 1893 and 1929. After WWII the U.S. has had nine recessions. © 2005 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Survey of Economics, 2/e O’Sullivan & Sheffrin 4 Business Cycles & Economic Fluctuations © 2005 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Survey of Economics, 2/e O’Sullivan & Sheffrin 5 Ten Postwar Recessions Peak Trough November 1948 October 1949 1.5 July 1953 May 1954 3.2 August 1957 April 1958 3.3 April 1960 February 1961 1.2 December 1969 November 1970 1.0 November 1973 March 1975 4.9 January 1980 July 1980 2.5 July 1981 November 1982 3.0 July 1990 March 1991 1.4 March 2001 -------- © 2005 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Survey of Economics, 2/e Percent Decline in Real GDP ------O’Sullivan & Sheffrin 6 Okun’s Law The relationship between changes in real GDP and the corresponding changes in unemployment is called Okun’s Law. According to Okun’s law, for every percentage point that real GDP grows faster than the normal rate of increase in potential output, the unemployment rate falls by one-half of a percentage point. © 2005 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Survey of Economics, 2/e O’Sullivan & Sheffrin 7 Okun’s Law: Example If the trend rate of real GDP growth is 3% per year and the unemployment rate is 5%, then ; If real GDP grows by 4% a year (1% point above its trend), then the unemployment rate will decline by 0.5% to 4.5%. If real GDP grows at only 2% per year (1% point below its trend), then the unemployment rate would rise 5.5%. © 2005 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Survey of Economics, 2/e O’Sullivan & Sheffrin 8 The Unemployment Rate During Recessions © 2005 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Survey of Economics, 2/e O’Sullivan & Sheffrin During periods of recession, marked by the shaded bars, unemployment rises sharply. 9 Procyclical and Countercyclical Measures Procyclical economic measures move in conjunction with real GDP. Investment spending, consumption spending and prices of stocks are all procyclical. The stock market always plunges sharply during recessions. Economic measures that fall as real GDP rises are countercyclical. Unemployment is countercyclical. Recessions are unpredictable and can arise as a result of external shocks or changes in economic policy. © 2005 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Survey of Economics, 2/e O’Sullivan & Sheffrin 10 Sticky Prices & Demand-side Economics Prices give the correct signals to all producers in the economy so that resources are used efficiently. If consumers decide to consume fresh fruit rather than chocolate, the price of fruit will rise and the price of chocolate will fall. The economy will produce more fresh fruit and less chocolate on the basis of these price signals. © 2005 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Survey of Economics, 2/e O’Sullivan & Sheffrin 11 Sticky Prices & Demand-side Economics If prices are slow to adjust, then the proper signals are not given quickly enough to producers and consumers. Arthur Okun classifies prices as: Auction prices, or prices that adjust nearly on a daily basis, such as food products. Custom prices, or prices that adjust slowly, or “sticky prices,” such as wages and some industrial commodities. © 2005 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Survey of Economics, 2/e O’Sullivan & Sheffrin 12 Sticky Prices & Demand-side Economics Wages are sticky because workers often have long-term contracts or are protected from wage decreases by minimum wage laws. If wages are sticky, then firms’ costs and their prices will be sticky as well. Sticky prices get in the way of the economy’s ability to coordinate economic activity, and to bring demand and supply into balance. © 2005 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Survey of Economics, 2/e O’Sullivan & Sheffrin 13 Sticky Prices & Demand-side Economics Typically, firms let demand determine the level of output in the short run. In the long run, prices fully adjust to changes in demand. In the short run, firms have negotiated contracts that keep input prices fixed. Sudden changes in demand will be met by changes in production with only small changes in prices. Keynesian economics refers to the determination of output in the short run based strictly on changes in demand. © 2005 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Survey of Economics, 2/e O’Sullivan & Sheffrin 14 Aggregate Demand (AD) The aggregate demand curve plots the total demand for GDP as a function of the price level. The price level refers to the average of all prices in the economy, as measured by a price index. © 2005 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Survey of Economics, 2/e O’Sullivan & Sheffrin 15 Components of Aggregate Demand Demand for GDP comprises the demand for goods and services by all sectors of the economy: the household sector (consumption), the business sector (investment), the government sector (government spending), and the foreign sector (net exports) © 2005 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Survey of Economics, 2/e O’Sullivan & Sheffrin 16 Aggregate Demand Slopes Downward Aggregate demand slopes downward for several reasons. Among them are: The wealth effect: as the price level falls, the real value of money increases and people find that they are wealthier. This concept is associated with the reality principle. Reality PRINCIPLE What matters to people is the real value or purchasing power of money or income, not its face value. © 2005 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Survey of Economics, 2/e O’Sullivan & Sheffrin 17 Aggregate Demand Slopes Downward Aggregate demand slopes downward for several reasons. Among them are: The interest rate effect: with a given money supply, a lower price level will lead to lower interest rates and higher consumption and investment spending. © 2005 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Survey of Economics, 2/e O’Sullivan & Sheffrin 18 Aggregate Demand Slopes Downward Aggregate demand slopes downward for several reasons. Among them are: The impact of international trade: a lower price level makes domestic goods cheaper relative to foreign goods; and a lower U.S. interest rate leads to a lower U.S. exchange rate which also makes domestic goods relatively cheaper than foreign goods. © 2005 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Survey of Economics, 2/e O’Sullivan & Sheffrin 19 Factors That Shift Aggregate Demand Factors That Increase Aggregate Demand Factors That Decrease Aggregate Demand Decrease in taxes Increase in taxes Increase in government spending Decrease in government spending Increase in the Decrease in money supply the money supply © 2005 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Survey of Economics, 2/e O’Sullivan & Sheffrin 20 Aggregate Supply The aggregate supply curve depicts the relationship between the level of prices and real GDP. We will consider two aggregate supply curves, one corresponding to the long run (the long run aggregate supply curve), and one to the short run (the short run aggregate supply curve). © 2005 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Survey of Economics, 2/e O’Sullivan & Sheffrin 21 The Long Run Aggregate Supply Curve The classical aggregate supply curve is the supply curve for the long run— when the economy is at full employment. The level of fullemployment output does not depend on the level of prices, but on supply factors—capital, labor and technology. This is why the classical AS curve is vertical. © 2005 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Survey of Economics, 2/e Long Run AS O’Sullivan & Sheffrin 22 The Long Run Aggregate Supply Curve Combined with the aggregate demand curve, the intersection of the classical AS curve and the AD curve determines the price level and the fullemployment level of output. The position of the AD curve depends on the level of taxes, government spending, and the supply of money. © 2005 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Survey of Economics, 2/e Long Run AS O’Sullivan & Sheffrin 23 The Long Run Aggregate Supply Curve An increase in aggregate demand does not change the level of output in the economy but only the level of prices. The main result from the classical model is that, in the long run, output is determined solely by the supply of capital and labor—not by changes in demand. © 2005 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Survey of Economics, 2/e Long Run AS O’Sullivan & Sheffrin 24 Crowding Out As we have seen, higher aggregate demand (i.e. higher government spending) in the classical model does not change the level of output. If the level of output remains the same but government spending increases, some other component of demand (consumption, investment, or net exports) must decrease. © 2005 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Survey of Economics, 2/e O’Sullivan & Sheffrin 25 Crowding Out Increased government spending “crowds out” other demands for GDP. PRINCIPLE of Opportunity Cost The opportunity cost of something is what you sacrifice to get it. At full employment, the opportunity cost of increased government spending is some other component of GDP. © 2005 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Survey of Economics, 2/e O’Sullivan & Sheffrin 26 Competing Shares of GDP © 2005 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Survey of Economics, 2/e O’Sullivan & Sheffrin 27 The Short Run Aggregate Supply Curve The Keynesian AS curve is relatively flat because, in the short run, firms adjust output more than they adjust prices. Since an increase in demand is met mostly by an increase in output, we say that aggregate demand primarily determines the level of output in the short run. © 2005 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Survey of Economics, 2/e O’Sullivan & Sheffrin 28 The Short Run Aggregate Supply Curve The level of output where the Keynesian AS curve intersects the aggregate demand curve need not be the full-employment level of output. Output may exceed the level of full employment when demand is very high, and fall short of full employment when demand is very low. © 2005 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Survey of Economics, 2/e O’Sullivan & Sheffrin 29 The Short Run Aggregate Supply Curve Because prices do not adjust fully over short periods of time, the economy need not always remain at full employment, or potential output. Changes in demand will lead to economic fluctuations, away from full employment, with sticky prices and a Keynesian aggregate supply curve. Only in the long run, when prices fully adjust, will the economy operate at full employment. © 2005 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Survey of Economics, 2/e O’Sullivan & Sheffrin 30 Adverse Supply Shocks Supply shocks are external events that shift the Keynesian aggregate supply curve. Adverse supply shocks result in lower output, lower employment, and higher prices. © 2005 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Survey of Economics, 2/e O’Sullivan & Sheffrin 31 Favorable Supply Shocks Favorable supply shocks are also possible. They lead to the best of both worlds: higher output and lower prices. Favorable supply shocks allow the economy to grow rapidly without incurring the risk of higher inflation. © 2005 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Survey of Economics, 2/e O’Sullivan & Sheffrin 32 From Short-run to Long-run Equilibrium As firms compete for labor and raw materials, wages and prices will tend to rise over time. This will cause the Keynesian aggregate supply curve to shift upward. This situation will continue as long as output exceeds potential. © 2005 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Survey of Economics, 2/e Long LongRun Run Long Run Long AS AS Run AS AS O’Sullivan & Sheffrin 33 From Short-run to Long-run Equilibrium The Keynesian aggregate supply will keep rising upward until it intersects the aggregate demand curve at full employment. Adjustments in wages and prices eventually take the economy from short-run Keynesian equilibrium to long-run classical equilibrium. © 2005 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Survey of Economics, 2/e Long Run AS O’Sullivan & Sheffrin 34