Marques_Burris_FinalPaper - Ideals

advertisement

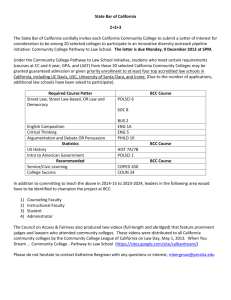

1 EXPLORING STUDENT PERCEPTIONS Exploring Student Perceptions and Experiences at the UIUC Black Cultural Center Marques J. Burris University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign 2 EXPLORING STUDENT PERCEPTIONS Abstract This study examined the experiences and perceptions of the Black Cultural Center (BCC) at the University of Illinois at Urbana Champaign (UIUC). In order to understand how students’ experiences at the BCC compare to the perceptions of the BCC, it is necessary to highlight the black student voices at the UIUC. For the current study, junior and senior undergraduate participants were recruited by utilizing snowball sampling. I utilized a qualitative methodology in order to assess the student experiences and perceptions of the BCC at UIUC. The findings indicate that students are more likely to attend the BCC if they feel comfortable, feel like they are building community, and/or have a high level of involvement with the BCC. 3 EXPLORING STUDENT PERCEPTIONS Introduction Stemming from the Black Student Movement of the 1960’s Black Cultural Centers (BCCs) have become institutional supports that provide programs and services to the entire campus community. Due to the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s, America’s higher education was drastically altered when more black students began to enroll. According to Patton (2006), the southern Black student population in the 1960s increased from 3,000 to 98,000 students. With this type of massive influx during the 60s, it is understandable how PWIs lack of preparation affected multiple black students. Black student’s academic, social, and cultural needs were not prioritized due to the lack of preparation of the PWIs (Patton, 2006). As the black student body increased at PWIs, black activism increased as well. With the Black Student Movement and the powerful philosophy of “Black Power,” black students were equipped with the tools of civil disobedience (Patton, 2006). This civil disobedience resulted in black students increased desire to alter the campus into a place that recognized and represented their culture. Thus, black studies courses were implemented at multiple universities along with financial assistance and increased recruitment for black students (Patton, 2006). In addition, cultural activities and Black culture centers (BCCs) were initiated in response to the high demands of Black students. Eventually, multiple universities introduced Black studies into the curriculum of the university in order to meet the academic demands of black students. Furthermore, BCCs were also established as a type of a support service in order to meet the social and cultural demands of the black student body (Patton, 2006). The initial mission of the BCC in a university setting was to be a place where values, attitudes, and knowledge could be shared between other students who had commonalities between one another. In addition, BCCs were utilized by students as a retreat and a safe haven from the environment of the PWIs (Patton, 2006). According to Pittman (1994), BCCs are beneficial to black students because they facilitate the process of identity development as well as enhance the campus climate. Hence, BCCs offer more 4 EXPLORING STUDENT PERCEPTIONS academic and social opportunities, which leads to higher retention rates for black students at PWIs (Pittman, 1994). Statement of Purpose Although there are many examples that support BCCs, the examples do not compensate for the lack of student voices that are pivotal to hear. The purpose of this study is to address the experiences and perceptions of the BCC at University of Illinois (UIUC). In order to understand how students’ experiences at the BCC compare to the perceptions of the BCC, it is necessary to highlight the black student voices at the UIUC. Important issue to examine at UIUC This issue is important and necessary to examine at the University of Illinois for many reasons. 1) This issue has yet to be addressed at the University of Illinois. 2) By comparing the perceptions of UIUC students to the experiences of UIUC students at BCCs, we may be able to understand how we can improve cultural centers to accommodate more students’ needs. 3) Once this study is complete, the results may draw attention to the level of support that is currently occurring at the BCC. 4) The results of the study will draw attention to not only BCCs but also cultural centers around campus. 5) In order to attain the proper funds for the cultural centers, it is necessary to have research that provides support for having cultural centers. Specific questions to be addressed The question framing this study is, how do black students make meaning of their interactions within the BCC environment and in what ways do their perceptions shape their experiences as a student at UIUC? The research question will be answered by utilizing a qualitative method. By utilizing a qualitative method, it will be easier to understand students’ experiences and perceptions of BCCs in detail. In addressing this I will ask the prospective participants the questions listed in figure 1. Although there will be multiple 5 EXPLORING STUDENT PERCEPTIONS questions, particular questions will be specifically for students who frequently attend the BCC and certain questions will be for students who don’t attend the BCC. Reflection As I research cultural centers, many people have started to question where my interest stems from. Some people that I have spoken to at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (UIUC) are interested in my topic and others have expressed their lack of concern. This disparity may be due to individual experiences people have had with cultural centers at UIUC or at another institution. After speaking to multiple people from various ethnic backgrounds, I have noticed that some people feel unwelcomed at certain cultural centers and some people feel as though they are essential for the success of underrepresented students. As I converse with people about the cultural centers at UIUC more in-depth, majority of people that I speak to expect me to be a very heavy advocate for the cultural centers, more specifically, the black cultural center on campus. This may be because of my ethnic background but as I express my plight with the cultural centers at the University of Illinois, some of these individuals are slightly surprised. The surprised reaction that people express may be because majority of people may expect me to agree with the way the cultural centers operate on campus. What people fail to realize is that my experience with culture centers in the mid-west is quite the opposite of my experience with cultural centers in the west coast. As an undergraduate student, I studied at California State University (CSU), Chico. Attending Chico the first year was a bit nerve wrecking at first. I felt isolated, lonely, lost, and a bit scared because I was one of the only black people on campus. Although I had attended a high school that was predominantly white, it was nothing like attending a university that was predominantly white. The black population during the year that I entered CSU, Chico was roughly around 1.5% out of a student body of 16,000 students. Although I came into the university as an (EOP) Educational Opportunity Program bridge EXPLORING STUDENT PERCEPTIONS 6 student, I felt underprepared to assimilate into the campus. The EOP group that I began my first year of college with was composed of roughly around 15 black students out of 100 students total. Out of the 15 black students in the program, there were 7 black males. Needless to say, I didn’t many see many people that looked like me my first year of college. Throughout the year, I met a few people in passing but I honestly didn’t build many lasting relationships during my freshman year. During my second year of college, the Cross Cultural Leadership Center (CCLC) was established. When I first entered into the CCLC, the student assistant at the desk greeted me and people from various backgrounds spoke to me without hesitation. It was there where I met more black students who were interested in getting involved on campus. I also began to form many relationships with students who weren’t black but were still very welcoming and genuine. I believe one specific major event that the cultural center put on during that year that helped me form stronger relationships with various people was the diversity summit. The diversity summit was a student and faculty retreat that was held each semester where students and faculty got to bond with one another in an isolated location. Bonding and trust activities were set up to help facilitate student and faculty engagement with one another. During my first summit, I learned how much in common I had with other students that did not share my ethnic background, sexual orientation, or sex. After coming back from the diversity summit, I realized that I had changed as a person. I was no longer infatuated with the differences between people, but rather the similarities I had with my peers. The CCLC soon became my second home because it was the most comfortable place on campus. Not only could students do their homework and socialize at the CCLC, but also various programs from multiple organizations were put on for anybody to participate in. I started to realize that the CCLC wasn’t just for a specific group, but rather anybody that wanted to socialize and get to know people. The various people that I met at the CCLC became very close friends throughout the rest of my time at CSU, Chico and many of them are still my friends today. EXPLORING STUDENT PERCEPTIONS 7 In comparison, the University of Illinois has cultural centers that are separated by ethnic groups, so it was quite a change when I visited them during my first year in Illinois. I first came in contact with the Bruce D. Nesbitt African American Cultural Center (BNAACC) when I was directed to go there in order to receive free printing. As I visited the center, there wasn’t anybody there besides one other individual who didn’t say much to me. After I printed the pages that I needed, I left the building without receiving one greeting from an employee or student there. The second time that I went to the BNAACC involved me meeting a friend. As I was meeting my friend there, I walked into the center and encountered multiple Black students. Apparently, I had just walked into an event called “speed-friending”. This program was put together for students who were involved in the 100 strong program. The particular event was created in order for new students to meet other students, thus creating retention amongst the black population at UIUC. I later found out that the 100 strong program focuses on building community amongst Black students in order to create retention and help them graduate. The majority of the students seemed pretty friendly and helpful as I asked questions. It seemed like all of the students were getting along pretty well but there wasn’t much diversity in the building because the program focused on Black students. At first, I was happy to see many of the Black students getting along but I still missed the CCLC because BNAACC lacked intercultural engagement. After visiting the other centers on campus, I then visited the BNAACC a 3rd time and I began to realize something very important between my previous institution and UIUC. I noticed the lack of intercultural engagement between the students at the cultural centers. Majority of the students who were from a specific ethnic background seemed to only participate in the programs organized by their designated cultural space. As I spoke to a few of the students in various cultural centers and asked them if they ever went to another cultural center their responses usually resulted in a negative way. One student in particular responded to my question by stating “Why would I go there?” I soon began to realize the differences 8 EXPLORING STUDENT PERCEPTIONS between the ideas behind various institutions on cultural centers could be an issue that has gone unnoticed in our system of higher education. Since noticing the differences between institutions, my ideas on exclusivity creating an equal environment for all have changed. My mindset has dramatically altered to creating a more inclusive learning environment for all. I feel like an environment where people engage with one another because of common interests rather than just one’s exterior is ideal. In order to understand what the University of Illinois can do to improve their cultural centers, I chose to focus on the BNAACC first to understand how students feel about the center. There are various Black students who choose to actively participate at the BNAACC and various Black students who don’t. My objective is to assess the reasoning behind both of the groups in order to come to a consensus on what can possibly be done to improve the center. By improving the center, more students from various backgrounds will feel more invited to attend and participate at BNAACC. Literature Review The Civil Rights Movement during the 1960s dramatically influenced the campus culture at various institutions. Patton (2006) noted, “during the 1960s at southern PWIs, the Black student Population leaped from 3,000 to 98,000 students, with similar increases in the North” (p. 628). Although the history of culture centers is quite recent, it is important to comprehend the history of black culture centers (BCCs) and what kind of role they played as attendance improved for black college students in the US. One piece of federal legislation that aided the initiation of changes in higher education for students of color was the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (Williamson, 1999). This act demanded a census of all postsecondary institutions in the U.S. that identified students by ethnicity or race. This helped acknowledge the extremely low amount of Black students at PWIs (Williamson, 1999). Thus, it put pressure upon PWIs to make their campus more diverse. The Higher Education Act of 1965 increased the amount and types of financial assistance accessible to people pursuing higher education (Williamson, 1999). In lieu of this, EXPLORING STUDENT PERCEPTIONS 9 African American students benefited greatly by acquiring: work-study opportunities, low-interest loans, and grants (Williamson, 1999). By the end of the 1960s, 8.4% of the entire college-going student population was African American students (Patton, 2006). Although there was a massive influx of students during this time period, majority of PWIs were unprepared to accommodate the academic, social, and cultural needs of these students (Patton, 2006). It was clear that the average black college student could not be treated as the common white student due to the unfair treatment that black students received. In response to this negative treatment by society, a Black Student Movement was initiated. This movement initially was led by a man named Stokely Carmichael, who helped empower a young generation with the philosophy “Black Power” (Patton, 2006). With this philosophy, the movement helped transform campuses into spaces of political and social change. Equipped with this philosophy along with civil disobedience, “black students wanted their culture recognized and integrated into the academic, social, and administrative functions of their universities” (Patton, 2004). Some of the demands included by the students involved: increased recruitment, financial assistance for black students, establishment of (BCCs) along with support for cultural activities (Patton, 2006). In lieu of this, by the late 1960s, multiple universities including San Francisco State University and Harvard established Black Studies into the curriculum of the university in order to meet the academic needs of the black students. Advocacy programs and support services such as BCCs were also established in order to meet the cultural and social demands” (Patton, 2006, p.628). These demands led to creating a social change that assisted black students to have a better experience at PWIs. This social change became increasingly relevant as time progressed into the 1980s. According to Sedlacek (1999), the United States witnessed a dramatic social change from the 1960s to the 1980s. Within this time frame, black students experienced multiple campus changes that influenced EXPLORING STUDENT PERCEPTIONS 10 their attitudes towards PWIs. In addition to the common college pressures a student goes through, black students must usually cope with cultural biases while learning how to connect his or her black culture with the dominant white campus culture (Sedlacek, 1999). Therefore, evidence illustrates that significant cultural differences between whites and blacks affect the way in which self-concept is exercised (Sedlacek, 1999). In order to properly assess how black students culturally adjust at PWIs, it is essential to look at theories that address their development in the setting. A very important theory that initially addressed the developing concerns of racial identity is Cross’s theory of psychological nigrescence. According to Evans, Forney, Guido, Patton, & Renn (2010) this term is best known as the progression of becoming black. Many black students at PWIs feel as though their blackness must be illustrated in some form or fashion on the campus. With this, the author addresses the importance personal identity, reference group orientation, and race salience is when black students are developing within an academic context. As students develop their personal identity at a PWI, they may start to develop their reference group orientation, which acknowledges the lens through which the student’s philosophical and political ideas are translated (Evans et al, 2010). In addressing race salience, students become more aware of the significance of their race and how it plays a vital role in an individual’s life (Evans et al, 2010). It is important to understand theory that addresses black students because by understanding theory, we will be able to understand the challenges an individual may face. By understanding certain student challenges, we will be able to better support these students by improving facilities that students may utilize. Although it is imperative to support practice with research, opposing views have challenged the establishment of these facilities (BCCs). Challenges Over the recent years, black cultural centers have met challenges due to opposing views. Many criticize the relevance and contributions of BCCs so it is necessary to create new strategies to support EXPLORING STUDENT PERCEPTIONS 11 BCCs. One of the misconceptions of BCCs is they foster separatism and self-segregation (Patton, 2006). This criticism was more common among university and college administrators during the black student movement. The opinion of these facilities preventing black students from assimilating into the dominant university environment still persists today. Some may argue that these centers oppose the mission of higher education by segregating black students from the rest of the students that are involved on campus (Patton, 2006). Patton argues that these perspectives stem from a misunderstanding of why BCCs were initially created. She also notes that these centers emerged out of the exclusion of black students from mainstream campus life and that exclusion still exists today (Patton, 2006). Although black students may feel excluded, some authors have questioned the need for BCCs due to the increase of diversity in recent years. Hefner (2002) argues that because the student demographics at PWIs are changing on a consistent basis, it would make sense to transition the BCCs into Multicultural centers. Hefner (2002) also addresses how separate cultural centers create tension amongst one another because the ethnic groups are competing for resources. This can lead to lack of funding for the cultural centers, which will be followed by inadequate support and lack of staffing (Hefner, 2002). The various experiences and perspectives on separate cultural centers can be best addressed by looking at past and current research on the topic. Research can help identify the roles that cultural centers currently have on campuses and how they can improve to make student experiences better at PWIs. Past Research One author recently chose to increase their understanding about BCCs roles on a campus by conducting a qualitative study at a specific institution’s BCC (Patton, 2006). Patton (2006) had the opportunity to interview approximately thirty-one students that ranged from freshman through senior undergraduate students. Patton (2006) found that the participants gained multiple benefits from the BCC, which included the following: a richer understanding of their community, increased pride in their shared EXPLORING STUDENT PERCEPTIONS 12 history, increased opportunities for involvement and preparation for student leadership, and an enrichment of strategies for thriving in college (Patton, 2006). Overall, Patton (2006) addressed the multiple positive experiences students had when they involved themselves in a BCC. However, Patton (2006) fails to address the negative experiences students may have had with the BCCs. Another focused on examining the multiple experiences ethnic minority college students had at a predominantly white institution (PWI). Jones, Castellanos, & Cole (2002) chose to examine student perspectives of the campus climate, school resources, and the quality of student service programs provided at the 4-year research institution. In order to assess these experiences, Jones et. al (2002) utilized a qualitative method to address the participants who were ethnic minority students who frequently visited the university multicultural center. For this study, focus groups were utilized in order to capture student thoughts and opinions about the institution. The various groups that were incorporated in the study included Native Americans, Asian-Pacific Americans, African Americans, and Chicano/Latinos (Jones et. al, 2002). Jones et al (2002) found that majority of the students conveyed the support for diversity on campus was nonexistent. Student experiences in the study were found to be extremely conflicted between the students in the group. Some students articulated that ethnicity and race played an important role in their college experience, although some students acknowledged having fewer problems with such issues (Jones et. al, 2002). In addition, Jones et al (2002) found that most of the African American students confessed to restricting their participation exclusively to multicultural organizations and events. Consequently, cultural centers were perceived as being unimportant to campus-wide operations because they isolated the experiences of ethnic minority students (Jones et. al, 2002). Although Jones et. al, addressed the multiple perspectives of the various groups, the authors’ primary focus was not on BCCs. However, the author did pinpoint a very important detail that was not addressed in prior studies. The author addressed the selfisolation that African American students take part in once they were involved in the cultural center. This is EXPLORING STUDENT PERCEPTIONS 13 note-worthy because it illustrates the negative impact a cultural center may have on a student’s experience at a PWI. Another study (Hall, Cabrera, & Milem, 2011) found that student experience at an institution could be positively impacted by engaging and interacting with other students who do not share identical ethnic identities. Hall et al. (2011) addressed the engagement between non-minority students and minority students, which translated into various experiences for the two groups. The authors found that the influence of ethnicity lessens by the end of the 2nd year in college. Thus, the two groups reported identical levels of positive engagement with diverse students during their sophomore year (Hall et al, 2011). The study focused on the engagement portion of student experiences rather than the institution facilities that assist minority students. Past research has illustrated that Latino and Black students identify their campus climate differently than White students do (Hall et al, 2011). These disparities in perception of the campus climate are extremely pertinent because they correlate to student grades, retention, and a student’s sense of belonging (Hall et al, 2011). The concluding study utilized a quantitative method to assess black student involvement at a PWI (Sutton & Kimbrough, 2001). The study found that majority of the black students professed themselves as leaders even though they did not hold a leadership position. The results of this study implicate majority of black students see themselves as leaders even though they may not hold a leadership position on campus. The study also found that the primary venue where Black students were involved in leadership positions were minority student organizations (Sutton & Kimbrough, 2001). This may be because students of color may feel a sense of belonging to a minority student organization rather than a traditional campus organization like student government. Although black students are underrepresented within these organizations, data indicates their involvement as orientation leaders and resident assistants at PWIs is steadily increasing (Sutton & Kimbrough, 2001). 14 EXPLORING STUDENT PERCEPTIONS Although these studies focus on the experiences and involvement of Black students at a PWI, more research needs to be accomplished before changes are made in order to improve their experience. In order to identify what is currently transpiring at University of Illinois (UIUC), I will conduct a study that focuses on Black students who are involved and not involved at the BCC. My objective is to understand the differences between these two groups by comparing the experiences and perceptions about the BCC made by these students. By assessing this, I hope to gain a better understanding of what can be done to improve the BCC so students will have a better experience at UIUC. A BCC that promotes leadership development, community, and academic assistance is needed to help shape the black leaders of tomorrow. With my research, I hope to gain insight to help promote this idea as a future student affairs professional. Methods In the current study, I utilized a qualitative methodology in order to assess the student experiences and perceptions of the BCC at UIUC. “Qualitative research is a type of educational research in which the researcher relies on the views of participants” (Creswell, 2011, p. 46). With this method, I was able to interpret student perceptions and experiences at the BCC more thoroughly. To properly evaluate these perceptions and experiences, I chose to utilize individual interviews in order to attain personal experiences from UIUC students. Sample and Procedure After receiving approval from the International Review Board (IRB), I began to recruit specifically upperclassman participants. Some of the participants I met by attending the BCC at UIUC. To randomize the sample, I chose to utilize the snowball effect. There were 4 participants in this study; all were students who currently attend the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. The participant sample was comprised of one woman and three men undergraduate students. I specifically chose undergraduate students who were upperclassman to capture in-depth student experiences about the BCC at UIUC. All of EXPLORING STUDENT PERCEPTIONS 15 my student participants identified as African American or Black American. I attempted to ask some acquaintances that I knew of who are familiar with the Bruce Nesbitt Cultural Center. Some of these acquaintances included students that do not consistently attend the cultural center. Before I interviewed the participant, I explained my study verbally and gave him/her a summary of what my research focuses on. I also informed him/her that the responses they provided for my research would be completely confidential. After I explained to the participant what my research consisted of, I handed him/her two copies of the informed consent for him/her to sign. The participants kept one of the copies and the other copy was returned to the course instructor. Within the informed consent, the participant had the option to choose if they would mind being recorded via audio. I also asked verbally if the participant would mind if I recorded them utilizing an audio recorder device. Once I interviewed one participant, I requested them to inform me of someone else that is or is not frequently involved with the BCC who may be interested in answering a few questions regarding the BCC at UIUC. During each individual interview, I informed each participant of the confidentiality that went along with participating in the study. For the most part, the participants were open and honest with their responses. Each student who agreed to take part in the study agreed to be a part of a private semi-structured interview. The interviews were all completed at the undergraduate library at UIUC in a secluded area. This was to ensure other individuals did not influence participant responses. Some of the research questions utilized in the study are located below: 1. What are the main reasons you attend the BCC? 2. Do you attend any of the other cultural centers? Why or why not? 3. How often do you attend the BCC or any of the events put on by the 1BCC? 1 For Interview Questions see Appendix A 16 EXPLORING STUDENT PERCEPTIONS All of the interviews took approximately 10 to 25 minutes to complete. The goal of the individual interviews was to ensure that all perceptions and experiences at the BCC were shared without being influenced by anyone else. After the interviews were conducted, the next step was to analyze the data. Data Analysis The data that was collected was analyzed by reading over the conducted interviews. I developed codes that correlated to my research questions. The list of codes that were produced from my research questions were the following: “Comfort level”, “Community Building”, and “BCC involvement”. These specific codes were then attached to a specific student’s response when expressing one of the codes mentioned above. By utilizing the codes, I attached individual codes to the quotes of the participants. After attaching the participant quotes to the code, I analyzed the coded data and grouped the quotes into patterns. These patterns are better known as themes. In addition, in order to keep the identities of the participants anonymous, pseudo names were utilized in this study. Findings After interviewing the participants, there were three themes that emerged from the data collected. The themes that emerged from the data illustrated the reasoning behind student attendance and level of involvement at the BCC. For students who choose to attend, the data illustrates that students attend the BCC because they feel comfortable attending, it is a good place for community building, and it allows for a better student experience. For students who choose not to attend, the data illustrates that students feel the exact opposite. In order to understand how these two groups have conflicting experiences, it is imperative to understanding the discrepancies between these two types of experiences. In understanding these discrepancies, we may better understand how to improve the BCC at UIUC so it can be more beneficial for students. EXPLORING STUDENT PERCEPTIONS 17 Comfort Level One of the first things expressed by the student participants was their comfort level in relation to the BCC at UIUC. The students who attended shared that the inclusive environment and welcoming attitude by the BCC staff made it easy to continually visit the center. Kenneth, a junior, expressed the reason he attends is because of his high comfort level. “I consider it my home away from home. I am not opposed to going to the other cultural centers but I just feel more integrated to the people of my own ethnic background.” Michelle, a junior, expressed how the BCC made her feel safe. “Racism seems to be a big thing on this campus. I sometimes feel unsafe walking near white frat houses because I feel like I will get lynched. If it weren’t for the black house, I wouldn’t be here.” When interviewing the students who didn’t attend the BCC, they expressed the complete opposite claim. Edward expressed his lack of comfort because of the cliquish vibe he got when he did attend. “They are more focused on creating a clique and if you aren’t apart of that clique you aren’t really welcomed. If you don’t look at things the way they do and do the things they do, you aren’t welcomed. They make it seem like we should feel privileged that it’s (BCC) there rather than focusing on welcoming students in.” Donald, a 5th year senior expressed his low comfort level was because he did not feel like his specific culture was accepted and promoted. “I felt excluded from the community because I wasn’t African. It’s hard to open up in a place where you are not accepted. We need to stick together but I feel that place ostracizes us and separates one another from really knowing ourselves on this campus and I really wish that would change.” Community Building EXPLORING STUDENT PERCEPTIONS 18 The BCC at UIUC has been known enhance community-building opportunities for multiple students. Through various programs, many friendships have been formed and sustained through the BCC. Kenneth addressed how some of his closest relationships came from the center. “The people there are the best thing. Some of the strongest relationships have been formed through the BCC. I met my mentor through the BCC. I’ve met a lot more people than I generally would have if I didn’t attend. It put me in connection with more people. I used to be shy but going to events at the BCC put me in a position to meet more people than I would have otherwise. Michelle also highlighted the social benefits of attending the BCC. “Once I got involved with 100 strong, I felt a sense of community. In terms of networking, I met a lot of great people. If something comes up involving free tickets or guest speakers we are always the first ones to get the tickets and talk to the speakers. If you show effort and put yourself out there, they help you out. They want to help you help yourself.” As a non-attendee, Edward’s experience differed as he expressed the detrimental effects of sticking to one group. “If you don’t attend, you are more open to mingling with different groups. If you do attend, you stick to what you know. It kind of retards diversity.” Donald also expressed some regret in not attending but still feels like he has benefited in other ways. “I have not been to certain events because I didn’t attend the BCC. I miss out on a lot of events. It has made me reach out to other cultures. Because of this, I have branched out to network with other people who are not black. It can limit you if you only associate yourself with Black people. Everybody in the world isn’t Black and White once you leave college.” BCC Involvement As many students start to become more involved at the BCC, the more times the students visit per week. In essence, I found that high level of involvement links to how consistently students would attend the center. Kenneth informed me how often he attends the BCC and the positions he held at the BCC. “I go to the BCC pretty much everyday, at least 4-5 times a week. I used to be a part of 100 strong, former publicity chair for it, and now I’m a general board member” EXPLORING STUDENT PERCEPTIONS 19 Michelle also expressed her level of involvement at the BCC. “Once I got involved with 100 strong, I felt a sense of community. Last semester, I was there everyday.” Discussion and Implications The data analysis of the interviews illustrated the discrepancy between students who decide to involve themselves at the BCC and students who do not. As for the students who did, they highlighted how the BCC played a crucial role in their development as Black students at a PWI. For the students who chose not to involve themselves at the BCC, they claimed that their experience has been more diverse because they were able to branch out to meet various types of people. By translating the data into three themes; comfort level, community building, and BCC involvement, I was able to understand the pros and cons of what the BCC does for students. This discrepancy between student experiences and perceptions about the BCC may be caused by multiple reasons. As Jones et al (2002) found, although race and ethnicity play a significant role in their college experience, some students acknowledge having fewer issues than others. All students do not all have the exact same experiences, which may explain why some students prefer to be involved at the BCC to others. Findings also suggest that the level of involvement at the BCC may increase or decrease the likelihood of students being retained at the BCC. Some of the participants that were heavily involved at the BCC were easily retained over students who were not involved at the BCC. The participants that held positions at the BCC were the ones who attended more frequently. These findings suggest that students who do not choose to hold positions revolving around the BCC may in fact lose interest in attending quicker than students that do hold positions. The two participants who did frequently attend the BCC held leadership positions, which resulted in frequent attendance at the BCC. Thus, students who didn’t hold leadership positions didn’t feel the need to attend a place where they weren’t known which left them feeling unwelcomed. The level of a 20 EXPLORING STUDENT PERCEPTIONS student’s involvement at a BCC may be linked to how comfortable a student may feel when attending the BCC. The findings illustrate that after frequently attending the BCC, a student feels welcomed because they feel like the BCC is their community. The most interesting finding was students understanding that becoming involved at the BCC usually led to segregating oneself from other groups that weren’t black. The students, who did happen to visit the other cultural centers, did it on rare occasions and only when it was mandatory or food was involved. This coincides with Hefner (2002) who suggests that BCCs lead to segregation, thus creating tension between other ethnic groups. In order to decrease infrequent visits to other cultural centers and organizations, it is necessary to have more intercultural programming so various students will have the opportunity to branch out of the BCC. In addition, the findings indicate that the BCC has become slightly repetitive with programs and discussions. If students feel as though the same programs and discussions are being carried out at the BCC, it is likely that students will become bored because they aren’t being challenged or intellectually stimulated. Implications Based on the findings, there are multiple things that can be done to improve this research. Unfortunately, the majority of the participants in the study were male. In order to conduct proper research, it is important to balance the perspectives of the each gender in the study so the perspectives carry equal weight. The majority of my findings focus on the social aspect of attending the BCC but they don’t address the academic experience. Further research should assess the academic benefits of attending the BCC. By addressing the academic benefits, the argument of the BCCs being essential on campuses may become stronger in the eyes of other researchers. The majority of the participants in the study also commented on the fact that the BCC is not for everyone. Whether you are more independent, self-motivated, or don’t have time, the BCC can have a certain impact on certain students’ lives more than others. EXPLORING STUDENT PERCEPTIONS 21 The purpose of this study was to obtain a better understanding of the student experiences and perceptions of the Black cultural center at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. The two groups that participated in the study composed of students who consistently attended the BCC and students who did not consistently attend the BCC. Overall, the themes that were found in the study included consisted of: level of involvement, comfort level, and community building. These three themes are themes that link to students consistently attending the BCC at UIUC. During the interviews, the participants did recommend that a few changes needed to be made to the BCC. Many of the participants felt that the BCC needs to diversify their programs and making the center more open and comfortable for more students. Future research should consider how student experience could correlate to student involvement at the BCC. Research should also assess the differences between multicultural centers and segregated cultural centers to capture the differences in student experiences between the two groups. Overall, cultural centers are not perfect but they do have many benefits for students. To enhance student experiences at an institution, further research must be accomplished so more underrepresented students will be retained at PWIs in the future. 22 EXPLORING STUDENT PERCEPTIONS Appendix: (Figure 1) BCC Attendees: What are the main reasons you attend the BCC? Do you attend any of the other cultural centers? Why or why not? How often do you attend the BCC or any of the events put on by the BCC? How do you feel about black students that don’t attend the BCC? How well do you get along with people that don’t attend the BCC? Why do you think that is? What is the best thing about the BCC? How has attending the BCC socially affected you? How has attending the BCC affected your experience at U of I? Why do you think that is? How do you think the BCC can improve to make the experience better for students? How would you improve the environment at the BCC so more students would want to participate? Does attending the BCC consistently confirm what it means to be black? Why or why not? BCC Non-Attendees: Have you been involved with the BCC at UIUC? Why or why not? How come you don’t attend the BCC? How do you feel about black students that do attend the BCC? Do you feel that people who attend the BCC purposely isolate themselves from others that don’t attend the BCC? Why or why not? What is the best thing about not attending the BCC? EXPLORING STUDENT PERCEPTIONS 23 How has not attending the BCC socially affected you? How has not attending the BCC affected your experience at U of I? Why do you think that is? What do you think is the downfall of attending the BCC versus not attending? How do you think the BCC can improve to make the experience better for students? How would you improve the environment at the BCC so more students would want to get more involved in the BCC? Does attending the BCC consistently confirm what it means to be black? Why or why not? 24 EXPLORING STUDENT PERCEPTIONS References: Evans, N. J., Forney, D. S., Guido, F.M., Patton, L.D., Renn, K.A. (2010). Student development in college: Theory, research, and practice (2nd edition). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. Edwards, J. (1994). Group rights v. individual rights: The case of race-conscious policies. Journal of Social Policy, 23(01), 55-70. Hefner, D. (2002). Black Cultural Centers: Standing on Shaky Ground? Black Issues In Higher Education, 18(26), 22-29. Hall, W., Cabrera, A., & Milem, J. (2011). A Tale of Two Groups: Differences Between Minority Students and Non-Minority Students in their Predispositions to and Engagement with Diverse Peers at a Predominantly White Institution. Research In Higher Education, 52(4), 420-439. Jones, L., Castellanos, J., & Cole, D. (2002). Examining the ethnic minority student experience at predominantly White institutions: A case study. Journal of Hispanic Higher Education, 1(1), 19-39. Kimmel, K., & Volet, S. (2012). University Students’ Perceptions of and Attitudes Towards Culturally Diverse Group Work: Does Context Matter? Journal Of Studies In International Education, 16(2), 157-181. Lee, S. M. (1993). Racial classifications in the US Census: 1890–1990. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 16(1), 75-94. Patton, L. (2004). From protest to progress? An examination of the relevance, relationships and roles of Black Culture Centers in the undergraduate experiences of Black students at predominantly white institutions (Doctoral dissertation, Indian University, 2004) Dissertation Abstracts International, 65, 292. Patton, L. (2006). The voice of reason: A qualitative examination of black student perceptions of black culture centers. Journal of college student development, 47(6), 628-646. Patton, L. D. (2006). Black culture centers: Still central to student learning. About Campus, 11(2), 2-8. Patton, L. D. (Eds.) (2010) Culture centers in higher education: perspectives on identity, theory, and practice Sterling, Va.: Stylus, Pittman, E. (1994). Cultural centers on predominantly White campuses: Campus, cultural and social comfort equals retention, Last Word. Black issues in Higher Education, 11, (October 6), 104. Princes, C. W. (1994). The Precarious Question of Black Cultural Centers Versus Multicultural Centers. EXPLORING STUDENT PERCEPTIONS 25 Sedlacek, W.E. (1999). Black students on White campuses: 20 years of research. Journal of college student development, 40, 538-550. Sutton, E., & Kimbrough, W. M. (2001). Trends in Black Student Involvement. NASPA Journal, 39(1), 30-40 Williamson, J. A. (1998) "We hope for nothing, we demand everything.”: black students at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Williamson, J. A. (1999). In defense of themselves: The Black student struggle for success and recognition at predominantly White colleges and universities. Journal of Negro Education, 92-105. Williamson, J. A. (2003) Black power on campus: the University of Illinois, 1965-75 Urbana: University of Illinois Press.