Making "Makin' It" Possible: Developing Critical Literacy

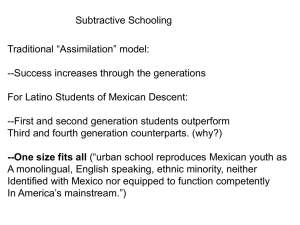

advertisement

Making “Makin’ It” Possible: Developing Critical Literacy Elizabeth Birr Moje University of Michigan William T. Grant Scholars Retreat June 2005 You should write a book, and you should call your book, On the Streets of Detroit, no, Underneath the Streets of Detroit. You should write about what we, what the people who live here, think of the city, not the police or the high society, but the people who really live here. [Ramiro, Ethnographic Interview, 2003] When people go to Hart Plaza for the Mexican festival or to Cinco de Mayo, the tourists only come and see the parade or go to the food booths, but they don’t see the real meanings underneath it, they don’t understand it. Overarching Project Goals To document and analyze how youth use and learn literate practices and various kinds of texts to learn content knowledge to develop and enact identities To integrate youth literacy and cultural practices with in-school literacy learning To provide a space for youth voices Everyday funds of knowledge and discourse: Youth culture, popular culture, ethnic culture Disciplinary knowledge and discourse: Science and Language Arts *content knowledge Youths Families Peers *literacy and language practices *identity development and strategic enactment *awareness of oppression and collective struggle *opportunities for action that benefits youth and communities Community-Based Organizations Schools Research Design and Foci Eight-year community ethnography in predominantly Latino/a community of Detroit Basic • • • • Research Component Youth literate practices Youth cultural, popular cultural, and school texts Youth national language practices Youth identity enactments and development – Developmental and spatial analyses • Youth literacy motivations and skills Intervention Research Component • Social action and critical literacy projects Data Sources & Participants School observations: Latino/a middle- and high- school students observed and informally interviewed in school classrooms 2-3 times per week, each week, for 7 years (n = 300) In-depth, semi-structured interviews: Latino/a youth (n = 65), ages 12-20 Community mapping: 2 formal maps; routine ethnographic mapping; youth-constructed maps Artifact collection (drawings, stickers, books, clothing) Data Sources & Participants Ethnographic observations and Interviews: Latino/a youth (n = 15), ages 12-20, followed over 5-7 years Informal and formal unstructured interviews: Parents, teachers, community leaders (n = 18) Surveys: 6th, 8th, and 9th grade students at 3 public schools and 1 private school (n = 350; targeted n = 775) Latino/a, African American, European American, Native American Additional samples in Boston, MA & Austin, TX; national sample via NCTE Analysis Methods Constant Comparative Analysis Discourse Analyses Narrative Analysis Hierarchical Linear Modeling Cluster Analyses Findings of the Basic Research Component These youth are strategic as they use literacy and language practices to position themselves and to enact particular identities. Racial/ethnic identities are, by far, the most salient identities in their everyday lives Popular cultural texts (and information technologies) play a prominent role in youths’ negotiations of ethnic/racial/class and affinity group identity. Findings of the Basic Research Component Middle-school aged youth in the study read a wide number of texts, but have few extended encounters with print prose (i.e., little book reading) As youth have aged, they’ve begun to read more books (girls) and newspapers/Internet sites (males) HR cluster analysis.ppt Youth find books they consider “real” most appealing; real does not necessarily connote nonfiction Exemplar: Popular cultural texts The Homies are a group of tightly knit Chicano buddies who have grown up in the Mexican American barrio (neighborhood ) of "Quien Sabe", ( who knows ) located in East Los Angeles. The four main characters are Hollywood, Smiley, Pelon, and Bobby Loco. Their separate and distinct personalities and characteristics together make up a single, composite entity that is the "HOMIES." In an inner-city world plagued by poverty, oppression, violence, and drugs, the Homies have formed a strong and binding cultural support system that enables them to overcome the surrounding negativity and allows for laughter and good times as an anecdote for reality. The word "Homies" itself is a popular street term that refers to someone from your hometown or, in a broader sense, anyone that you would acknowledge as your friend. In use in the West Coast Latino community for decades, the word "Homies" has crossed over into the now mainstream Hip-Hop street culture that has taken America's young people by storm. -Dave Gonzales [creator of Homies] Exemplar: Popular cultural texts I2: So what do they express about being Mexican? What do you think they express? Is there anything in particular that’s part of the point? M: The way Mexicans live . . . . Or things like sometimes these people become what they are because of problems they face. So yeah, that’s what they explain why they are the way they describe them. . . . I2: So the thing that makes them all what they are is that they tell you something about— M: --The background of the people. I2: The background of the people. But they’re supposed to be inspiring? They’re supposed to be inspirational? Like people whose stories, they’ve overcome something difficult? M: Yeah, because they have graduation or overcoming everything. They tell you to finish school, and stay cool and all that stuff. Stay out of drugs. Some of them try to take a message to the people. Findings Young people’s understandings of ethnic and racial selves are changing as they encounter new identity contexts (i.e., physical or geographic spaces, relationships, and time periods) Movement across geographic spaces takes them into “contact zones” Popular cultural texts (i.e., books and mass media) provide “home fronts” You should write a book, and you should call your book, On the Streets of Detroit, no, Underneath the Streets of Detroit. You should write about what we, what the people who live here, think of the city, not the police or the high society, but the people who really live here. Underneath the Streets of Detroit: Youth Social Action and Critical Literacy Projects “To tell people what our community is really like” Target Products: Individual Photoessays Individual Powerpoint presentations Group Video Individual book chapters Group Learning Goals: To learn more about own community To learn how to do research To learn better literacy skills To learn how to work with a group better Major Assertion of Intervention Component Youth are already capable of critique . . . What they don’t have is: Content knowledge and vocabulary Comprehension skills and strategies Research skills and strategies Synthesis skills and strategies Communicative skills and strategies Models National Assessment of Educational Progress (1998) 4th grade 8th grade 12th grade Below basic .38 .26 .23 Basic .24 .38 .32 Proficient .31 .33 .40 Advanced .07 .03 .06 Disproportionate numbers of ethnic and racial minority students and children who live in poverty are represented in the BELOW BASIC and BASIC categories The “Steps” Setting Individual Learning Goals Measuring Knowledge/Attitudes External measurement Self-measurement Group Conversations Learning Goals Target Products Project Brainstorming Project Research Project Refinement Questions Claims/Conclusions Project Presentation Individual Learning Goals, May 04 Yolanda: I want to learn how to put a book together from information that we get. I want to improve my English and writing. I want to improve more social [build social skills]. Ramiro: The main things that I’m trying to get out of this project is to see or project our city in a different way (good way). And to also improve my moral as well as how I see things. Also learn how to work as a team and see how other people see things. Individual Learning Goals, May 04 Pilar Learn more about my community Improve my writing Improve peoples idea of Detroit Improve peoples idea of me Panchito: I realy want to know why the pople write on the walls I believe that the people that due this thing are people that want expresar lo que ciente o rayan because some friends rayan tambien. Quiciera saber y descubrir more people that write y juntarnes para poder hacer une que halplara about something good olgo que le gustara a la gente que le daria gusto ver, algo que fuera como una motivaicon; que le diera gusto y Felizidad a todas las personas que pudieran ver este mensage. Por favor Consume lo q‘ tu cerebro produce! Initial Project Brainstorming, May, 04 Show the struggles we’ve lived through Police or government don’t do anything about it: Police have stopped people for drug trafficking, but people who did these things eventually get on parole Political leaders aren’t in touch in with the different levels of the community • If the government would have the same structure that gangs or drug syndicates have, they’d be successful because the leaders know what different levels are doing—the illegal drug industry is like a beautiful time piece; everything goes back to the Roman empire, the structure, everything. They don’t know how to go back, they should learn history. You can’t show care if you haven’t been taken care of. Show school drop-out rates: You’re showing that schools aren’t doing anything about gang violence. Project Brainstorming (Sept 04) “Get other people to have a different perspective of Detroit--outside of Detroit, in the suburbs and in Michigan, to show about our community” To “compare media representations with our real lives” Media representations of Detroit are skewed “because there are more minorities in Detroit” Project Brainstorming (Sept 04) “To learn about our community” Y: “Like the Freedom Festival, everything on the news, it was showing only part of the problem, we need broader perspectives on the problems” To explore issues of discrimination: racial/ethnic and socioeconomic: Background, when it started, and how it continues in the US Project Brainstorming (Sept. 04) To “see how other communities live and how they take care of their people” R: “’cuz like White people, man, are cold-blooded; they leave their old people and parents in the retirement homes.” Youth Data Collection Methods Independence festival photos; Cinco de Mayo Census data and crime rate data for cities across the world Media representations of different cities across the world “Experiments where we test theories of discrimination” Interviews/Surveys Reading studies about discrimination Are Chicanos the Same as Mexicans? Here are some reasons why many U.S. citizens of Mexican extraction feel that it is important to make the distinction: • Not "Americans" by choice A scant 150 years ago, approximately 50% of what was then Mexico was appropriated by the U.S. as spoils of war, and in a series of land "sales" that were coerced capitalizing on the U.S. victory in that war and Mexico’s weak political and economic status. A sizeable number of Mexican citizens became citizens of the United States from one day to the next as a result, and the treaty declaring the peace between the two countries recognized the rights of such people to their private properties (as deeded by Mexican or Spanish colonial authorities), their own religion (Roman Catholicism) and the right to speak and receive education in their own tongue (for the majority, Spanish) [refer to the text of the treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo]. Therefore, the descendants of this population continue to press for such rights, and many hold that theirs is a colonized land and people in view of the fact that their territory and population was taken over by military force. • Mexicans first, "Americans" second? Another and more numerous class of U.S. citizens of Mexican extraction are either descendants of, or are themselves, people who conceive of themselves as temporarily displaced from Mexico by economic circumstances. As opposed to the waves of European migrants who willingly left their countries due to class and religious discrimination, and sought to make their lives anew in the "new world" and never to return to the "old land," these displaced Mexicans typically maintain strong family ties in Mexico (by visiting periodically, and by investing their incomes in homes or kin in Mexico), and usually intend to return to Mexico provided they can become economically secure. Therefore these people maintain and nurture their children in their language, religion and customs. However, There is great tension within this population between those of Mexican birth who conceive of themselves as temporary guests in the U.S., and their descendants who are born in the U.S., are acculturated with the norms of broader U.S. society in public schools, and are not motivated by the same ties that bind a migrant generation of Mexicans. This creates a classic "niche" of descendants of immigrants who are full-fledged U.S. citizens, but who typically do not have access to all the rights and privileges of citizenship because of the strong cultural identity imbued in them by their upbringing and the discriminatory reaction of the majority population against a non-assimilated and easily identified subclass. This group of people feels a great need to distinguish itself from both its U.S. milieu and its Mexican "Mother Culture," which does not typically welcome or accept "prodigals." This is truly a unique set of people, therefore, in that it endures both strong ties and strong discrimination from both U.S. and Mexican mainstream parent cultures. The result has been the creation of a remarkable new culture that needs its own name and identity. One In-process Project BothSidesOfTheCoin.ppt Thank you, W. T., for The cash A broad-based, longitudinal program of research New grants Development of an interdisciplinary and ethnically diverse research team Capacity building of future scholars Opportunities to learn new methods New partnerships and friendships Attention to youth, families, and communities Acknowledgements Research Colleagues Ruth Athan, Rosario Carrillo, Kathryn Ciechanowski, Tanya Cleveland, Tehani Collazo, Lindsay Ellis, Jacque Eccles, Jeanne Freidel, Katherine Kramer, Ritu Radhakrishnan, Paul Richardson, LeeAnn Sutherland, Laura VanDerPloeg, Helen Watt Mentors Shirley Brice Heath Paul Pintrich