Nonverbal Influence

advertisement

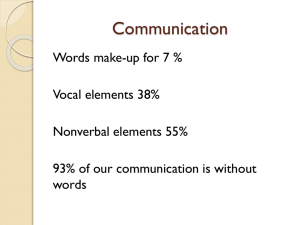

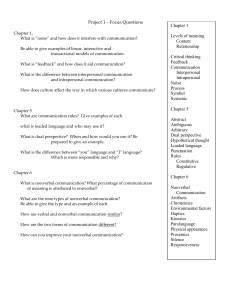

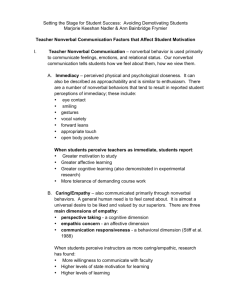

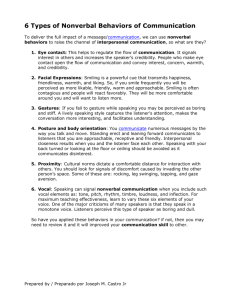

Nonverbal Persuasion Overview of nonverbal communication Nonverbal communication is powerful – Burgoon, Buller, & Woodall (1989) 60% of the socio-emotional meaning of a message is carried via nonverbal cues • Nonverbal influence can be subtle – Fisher, Rytting, & Heslin (1976): Library patrons who received an “accidental” touch were more likely to return books on time • Overview continued You cannot “read a person like a book.” – No one-to-one correspondence between a particular nonverbal cue and its specific meaning – “individual difference perspective”: nonverbal behavior is highly idiosyncratic • Not all of nonverbal communication is obvious or “intuitive” – Burgoon & Guererro (1994) relationship between posture and liking – eye contact and deception detection • Nonverbal persuasion in action • Body Image: – Media depictions of the ideal female body type contribute to body dissatisfaction and eating disorders in women. – the average American model is 5'11" tall and weighs 117 pounds – the average American woman is 5'4" tall and weighs 140 pounds. More nonverbal influence in action Nothing says “peace” and “ecology” like getting naked • anti-war activists: naked dissidents spell “no war.” • logging protesters: female environmentalists bare their breasts to stop loggers from cutting down old growth forests • Nonverbal persuasion in action When Bush claimed “mission accomplished” aboard the U.S.S. Abraham Lincoln on May 1, 2003, the photo-op backfired as the war went on and on • Janet Jackson’s “wardrobe malfunction” during the Superbowl prompted the FCC to clamp down on risqué shows • The Direct Effects model of Immediacy Andersen (1999): warm, involving, immediate behaviors enhance the persuasive effects of a message – It is easier to comply with those we like – easier to trust warm, friendly people • Single channel immediacy (eye contact) increases compliance, as does multichannel immediacy (eye contact and smiling) • Expectancy Violations Theory • Buller & Burgoon (1986) People have expectations about what constitutes appropriate behavior in social situations – example: elevator etiquette • Violations of these expectations are perceived positively or negatively, depending upon: – the status, reward power of the communicator – the range of interpretations that can be assigned to the violation – the perception/evaluation of the interpreted act • Types of nonverbal cues • • • • • • Proxemics (distance) Vocalics (paralanguage) Haptics (touch) Chronemics (time) Kinesics (behavior) Artifacts (dress, belongings) Proxemics Edward Hall’s space zones • Effective persuasion requires honoring space zones (e.g. not violating expectations negatively) – Public distance: 12-25 feet – Social or formal distance: 4-12 feet • Most U.S. business relationships begin in the Social Zone – Personal or informal distance: 3 1/2/-4 feet • Managers and co-workers who enter the Personal Zone too quickly risk conflict and distrust. – Intimate distance: 18 inches or less • Segrin’s (1993) meta-analysis of proxemics studies “close” distance was typically operationalized as 1-2 ft., “far” was usually 3-5 ft. • of eight studies examined, “the effect for closer proximity was consistent. Close space produces greater compliance than distant space” (p. 173) • Advice on vocal delivery A faster speech rate enhances perceptions of credibility more than a slower speech rate • Increasing intonation, volume, and pitch variation increases perceptions of credibility • – Monotone speakers bore their audiences • Limiting or controlling nonfluencies – Excessive “ums, uhs” decrease credibility • Use an assertive style of speaking – conveys confidence and conviction • • Minimize casual speech, “valley talk,” colloquialisms Moderation should be exercised with all vocal cues (avoid extremes in any one category) Haptics (touch) • • Self touch (adaptors) tend to decrease credibility The “Midas Touch” and compliance gaining – Gueguen (2003) females boarding a bus “discovered” they didn’t have a ticket. They asked the driver to let them ride for free • Drivers who were touched were more likely to comply with the request than drivers who weren’t touched – Gueguen & Fischer-Lokou (2002): A person asked a stranger to watch his or her large, unruly dog for 10 minutes while he/she went into a bank • 55% of subjects who were touched consented • 35% of subject who weren’t touched consented – Crusco & Wetzel (1984), Hornick (1992) food servers who used touch received larger tips Segrin’s (1993) meta-analysis of touch studies The most common experimental paradigm involves light touch on the upper arm or shoulder while making a request • Of 13 studies examined, “it can be concluded touch always produces as much, and in many cases more compliance than no touch, all other things being held equal” (p. 174) • More on touch and compliance gaining Why is touch so persuasive? – Conveys immediacy, warmth – Increases liking – Serves as a distraction • Caution: too much touch can backfire – May be perceived as a negative violation of expectations, e.g., insincere, coercive, or a form of sexual harassment • Chronemics Time spent waiting confers power, status – example: M.D.s and patients – example: Professors and students • Tardiness can negatively impact credibility – Burgoon et al (1989): late arrivers were considered more dynamic, but less competent, less sociable than those who were punctual • There are huge cultural differences in timeconsciousness • Cultural differences in perceptions of time • Western culture: M-time emphasizes precise schedules, promptness, time as a commodity – – – – – “time is money” “New York minute” “Down time” “Limited Time Offer!” “Must Act Now” • Other cultures: P-time cultures don’t value punctuality as highly, don’t emphasize precise schedules – “island time” – Sioux Indians have no spoken words for “late” or “tardy” Time as a sales strategy • Urgency as a sales tactic – must act now, limited time offer, first come first serve – Time windows; shop early and save, super savings from 7am-10am – 1 hour photo, Lenscrafters, Jiffy Lube, drive through banks, etc. • Non-urgency as a sales strategy – 90 days same as cash – No No No sales – mega-bookstores that encouraging browsing, lingering Kinesics (movement, gesture, posture, facial expression, eye contact) Beebe (1974) eye contact and perceptions of honesty • Eye contact and compliance gaining – Robinson, Seiter, & Acharya (1992) successful panhandlers establish eye contact – Kleinke (1989) compared legitimate and illegitimate requests when using eye contact – LaFrance &Hecht (1995) greater leniency for cheaters who smiled • Segrin’s (1993) meta-analysis of gaze studies Gueguen & Jacob (2003): Direct gaze produced greater compliance with a request to complete an oral survey than an evasive glance • Gaze has been studied in the context of hitchhiking, borrowing change, handing out pamphlets, obtaining change, donating money for a charity • “gaze produced greater compliance than gzae aversion in every one of the 12 studies” (p. 173) • Kinesics: facial expression • Birdwhistle (1970): the face is capable of conveying 250,000 expressions Kinesics: smiling Smiling increases sociability, likeability, attraction • LaFrance & Hecht (1995) Smiling students who were charged with academic dishonesty received greater leniency • Heslin & Patterson (1982): smiling by food servers increased tips • Excessive smiling can hinder credibility • Kinesics: body language DePaulo (1982): “mirroring” body language facilitates compliance • McGinley, LeFevre, & McGinley (1975): an “open” body posture is perceived as more persuasive than a “closed” posture • Kinesics: gestures, appearance, height and weight • • Gestures can send subtle or not so subtle cues Physical appearance – Mixed messages in women’s magazines – Brownlow & Zebrowitz (1990): baby faced versus mature face persuaders and credibility – Height and weight: • Knapp & Hall (1992) survey of height and starting salaries • Height and perceived credibility • Argyle (1988) endomorphs more likely to be discriminated against Artifacts Material objects as an extension of the self • Uniforms and compliance gaining – Lawrence & Watson (1991): requests for contributions were greater when requesters wore uniforms – Bickman (1971): change left in a phone booth was returned to well dressed people 77% of the time, poorly dressed people only 38% of the time – Clothing signifies authority • Example: Milgram (1974) • Clothing and status factors • Gueguen (2003) Shoppers were less likely to report a welldressed shoplifter than a casually dressed or poorly dressed shoplifter. – Neatly dressed: suit & tie (90% did not report) – Neutral: Clean jeans, teeshirt and jacket, moccasins (63% did not report) – Slovenly: Dirty jeans, torn jacket, sneakers (60% did not report) More on clothing and status factors • Gueguen & Pichot (2001): pedestrians at a cross-walk were more likely to “jaywalk” by following a well-dressed person across an intersection displaying a red light – Control condition: 15.6% violations of do not walk signal – Well-dressed: 54.5% violations – Casually dressed: 17.9% violations – Poorly dressed: 9.3% violations Segrin’s (1993) meta-analysis of apparel studies Operationalizations of clothing or attire were quite diverse (hippie, professional, bum, formal, uniform, etc.) • In general “the more formal or high status the clothing, the greater the compliance rate obtained” (p. 177) • Attractiveness and social influence Stewart (1980) studied the relationship between attractiveness and criminal sentencing – handsome defendants were twice as likely to avoid a jail sentence • Benson, Kerabenic, & Lerner (1976): both sexes were likely to comply with a request for aid or assistance if the other was attractive •