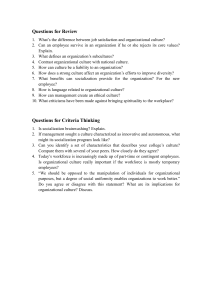

Perspectives on Culture

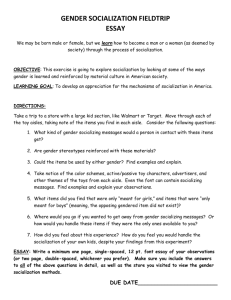

advertisement

Chapter Two Culture and the Culture Learning Process Defining Culture Culture is socially constructed. Culture is shared by its members. Culture is both objective and subjective. Culture may be defined by geography, ethnicity, language, religion, history, or other important social characteristics. Culture is socially transmitted. Culture in Everyday Use Terms commonly used to describe social groups that share important cultural elements are: Subculture Microculture Ethnic group Minority group People of color Subculture Subcultures share characteristics that distinguish them from the larger society in which they are embedded; these characteristics may be a set of ideas and practices or some demographic similarity. Some examples of subcultures are: Corporate culture Adolescent culture Drug culture Culture of poverty Academic culture Microculture Microcultures also share distinguishing characteristics but tend to be more closely linked to the larger society, often serving in mediating roles. Some examples of microcultures are: The family The workplace The classroom The school Ethnic Group Members of ethnic Some examples of groups share a ethnic groups are: common heritage, a Irish American common history, Native and often a American common language; Lebanese loyalty to one’s American ethnic identity can be very powerful. African American Minority Group Members of minority groups occupy a subordinate position in a society; they may be separated from the dominant society by disapproval and discrimination. Some examples of minority groups in the U.S. are: Racial minorities Women People with disabilities Language minorities People of Color This term refers to members of nonwhite minority groups; it is often preferred to the term “minority group,” but does not clearly identify specific loyalties. For example, native Spanish-speakers may identify themselves as Hispanic people of color, but their cultural identity may be as Puerto Ricans, Mexicans, or Salvadorans. Culture Solves Common Human Problems Means of communication—language Determination of power—status Regulation of reproduction—family Systems of rules—government Relationship to nature—magic, myth, religion, science Conception of time—temporality Significant lessons—history Cultural representations—music, story, dance, art The Contributions of CrossCultural Psychology While sociologists and anthropologists study groups and psychologists study individuals, cross-cultural psychologists study the interactions that occur when individuals from different groups meet. Cross-cultural psychologists may approach this problem from one or both of two perspectives: Continued… Culture Is Both Objective and Subjective Objective culture Physical artifacts Language Clothing Food Decorative objects Subjective culture Attitudes Values Norms of behavior Social roles Meaning of objective cultural elements Two Ways to Understand Culture Culture-specific approaches Culture-general approaches Help to understand a particular cultural group (for example, Native Americans) Help to understand how culture “works” in people’s lives; a universal perspective Do not account for in-group differences Suggest questions to ask of any culture The Culture Learning Process Sources of cultural knowledge and identity Individuals in complex societies like the United States tend to identify themselves as belonging to various cultural and social groups, depending on their personal biographies. There are twelve major sources of cultural identity that influence teaching and learning. Sources of Cultural Identity (Figure 2.1) Cultural Knowledge is Transmitted by People and Experiences We gain the knowledge that contributes to our cultural identities through interaction with various socializing agents These agents mediate our cultural knowledge in particular ways Important Socializing Agents (Figure 2.2) How We Learn Culture: Socialization Three stages of socialization Primary socialization—of infants and young children by the family and early care-givers Secondary socialization—in childhood and adolescence, by the school, the religious affiliation, the peer group, the neighborhood, and the media Adult socialization—the workplace, travel, assuming new roles in life Some Results of Socialization Because the process of socialization is intended to cause individuals to internalize knowledge, attitudes, values, and beliefs, it has several results which should not be surprising: Ethnocentrism Perception Categorization Stereotypes Ethnocentrism Ethnocentrism is the tendency people have to evaluate others according to their own standards and experience While this tendency can help bind people together, it can also present serious obstacles to cross-cultural interactions Perception Stimuli received by our senses would overwhelm us if it weren’t somehow reduced; thus… What we perceive—what we see, hear, feel, taste, and smell—is shaped in part by our culture. Categorization Categorization is the cognitive process by which all human beings simplify their world by grouping similar stimuli. Our categories give meaning to our perceptions. A prototype image best characterizes the meaning of a category. Example: for the category “bird,” we usually think of robins, not chickens Stereotypes Stereotypes are socially-constructed categories of people. They usually obscure differences within groups. They are frequently negative, and play to ethnocentric ideas of “the other.” Some Limits on Socialization While socialization is a powerful process, it does have limits. It is limited by a child’s physical limits. It is limited because it is never finished, and thus never absolute; it can be changed. It is limited because human beings are not passive recipients, but also actors in their environments. Understanding Cultural Differences In a complex, pluralistic society like the United States, all people are in some way multicultural. While we all draw on common sources of knowledge, we are socialized by different agents, with different perspectives on that knowledge. The Culture-Learning Process (Figure 2.3) Variations in Cultural Environments Although the sources of cultural identity are the same in all society, the content in those sources may be different. Moreover, each community varies considerably in the number and character of its socializing agents. Continued… Given this complexity, it is wise to consider the immense variation of possible cultural elements in our own lives and in the lives of others. Despite this enormous potential for variation among individuals and within groups, there are similarities or generalizations that can be made about individuals who identify with particular groups. What is needed is a more sophisticated way of looking at diversity. Building a positive attitude toward diversity involves several elements: Questioning the “dominant model,” or the prototype image Questioning stereotypes Looking for commonalities among our differences Thinking of differences as resources to learn from Something to Think About By ignoring the cultural and social forms that are authorized by youth and simultaneously empower and disempower them, educators risk complicity in silencing and negating their students. This is unwittingly accomplished by refusing to recognize the importance of those sites and social practices outside of schools that actively shape student experiences and through which students often define and construct their sense of identity, politics, and culture. --Giroux and Simon