Analyzing Local Information Policies

advertisement

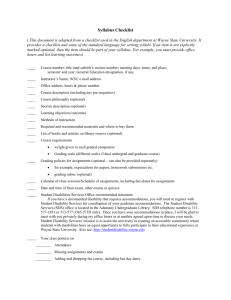

Running Head: ANALYZING INFORMATION POLICIES Problem One: Analyzing Local Information Policies Kristina Olsen Wayne State University 1 ANALYZING INFORMATION POLICIES 2 Problem One: Analyzing Local Information Policies As a student in an information science graduate program, and as with many graduate and undergraduate programs, there exists an information policy environment that affects one’s academic progress. Information policies are developed to protect the student’s privacy as well as promote the flow of information. Yet, it is difficult to clearly define what constitutes an information policy. The subject of information policy is wide-ranging and elicits many definitions from different information professionals. For instance, Maxwell (2003) defines information policy as “social, political, legal, economic and technological decisions about the role of information in society. These decisions operate both at a societal level when applied to the national and international policy, and at an instrumental level, as they impact the creation, dissemination, use and preservation of information.” Information policies can be found at the local levels within the Wayne State University Library System and the School of Library and Information Science. They are also at the higher, institutional level and those even higher at outside institutions such as the state and local government and third party network technologies. Although Maxwell’s definition of information policy is comprehensive and depicts the different levels of where information policies can reside, it is not wholly sufficient for the intended purpose of evaluating Wayne State University’s information policy environment. The definition leaves matters such as copyright, personal privacy, and plagiarism into question; are these areas of information policy. The British Columbia Library Association helps answer this question with a reconstructed definition: “Information policy determines the kind of information collected, created, organized, stored, accessed, disseminated and retained. Who can use the information, whether there ANALYZING INFORMATION POLICIES 3 will be charges for access, and the amount charged, is also covered. Usually associated with government information, information policy also established the rules within which private information providers and the media operate” (What is Information Policy, 1998). Therefore this definition allows for the consideration of Duff’s (2004) “Normative List of Information Policy Issues”: freedom of information; privacy; data protection and security; official secrets; libraries and archives; scientific, technical and medical documentation; economics of government publications; copyright and intellectual property; national information infrastructure; international information flows. Not all of these information policy issues will be included in the evaluation of the information policy environment, but this allows for a more accurate assembly of information policies. Furthermore, an institution, such as Wayne State University, can use its information policies to produce and better equip its students before sending them into the workforce. An established information policy can “[…] enable effective decisions on resource allocation; promote interaction, communication and mutual support between all parts of the organization, and between it and its ‘customers’ or public […]” (Orna, 2008). Clear information policies allow for the protection of students’ privacy, a concise understanding of what is expected of them through course syllabi, access to course material and resources, and better communication and use of technology. Accordingly, Wayne State University’s information policy environment will be examined by looking at the policies found on the institution’s web site and course syllabi and general information policies affecting the graduate students in the library and information science program will be identified. The relationships between local information policies and higher-level ANALYZING INFORMATION POLICIES 4 policy making bodies will be studied. Lastly, a look at how these policies are integrated into the graduate student’s courses and agenda as well as their affect on the student’s everyday life. The information policies located on the university’s main web site and the school of library and information science web site fell into six categories: funding, protection of personal privacy, freedom of access, intellectual property rights, literacy/student support, and information technology. The categories most lacking in polices are protection of personal privacy and freedom of access; where as, information technology and literacy/student support have the most. This gap in information policy is significant. There are many policies regarding information technology and student services and literacy, but the absence of privacy protection policies will soon pose a problem. However, one must consider that this deficiency maybe due to an overarching policy, such as the Family Education Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA), limiting the need for other protection policies. Some areas may need several policies due to inefficiencies within the policies. Therefore, there will be overlaps of some information policies to fill the missing links of others. See Appendix A for a diagram of general information policies. After locating and distinguishing the missing areas of information policy, the relationship between the local levels and the higher-level information policies was reviewed. In this instance, the policies were divided into four categories: academic integrity and plagiarism, student privacy and information security, student progress and grading, technology and information access. These categories were chosen by the frequency of mentions between the course syllabi and the web sites. An illustration of a higher-level to local level relationship is the Student Code of Conduct. The Student Code of Conduct is a higher-level Wayne State University policy, but is referenced several times within local level web sites, WSU Library System and the School of ANALYZING INFORMATION POLICIES 5 Library and Information Science and course syllabi. Another higher-level policy referenced throughout the local level is the Acceptable Use of Technology Resources. However, there are no local level policies that are also higher-level policies. For instance, the School of Library and Information Science developed a plagiarism quiz to further educate its students about the topic. This is a policy tool that should be incorporated into higher-level policies. Another example where a local level policy should be referenced at another level is the Copyright Guidelines for Posting to Blackboard. This is referenced on the WSU Library’s web site. However, this could also be stated in the School of Library and Information Science policies. Blackboard is a tool used by most everyone in the program and by including this policy with other information technology policies, the student and faculty is allowed easy access for reference. In addition to including more policies within the local level for easy accessibility, it is important to note three other policies developed by other institutions. First, the most significant policy regarding student privacy and information security is the Family Education Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA). This act was designed by the U.S. Department of Education, where the School of Library and Information Science and Wayne State University abide by this law. This is referenced in each syllabus as well as on WSU’s main web site. However, this is another policy that should be accessible through the School of Library and Information School’s policies and the WSU Library System policies. The second policy is the Library Privacy Act and third is the Merit Acceptable Use Policy. The Library Privacy Act is a law instituted from the state of Michigan regarding the confidentiality of library materials and the patron. Where the Merit Acceptable Use policy is a policy enacted by Wayne State University’s network provider. These policies are at the ANALYZING INFORMATION POLICIES 6 appropriate levels and do not need to be placed elsewhere. See Appendix B for a table depicting the policies between local level and higher-level policy making bodies. After identifying the information policies and analyzing the relationships between local level and higher-level policies, how the information policies affect the graduate student’s everyday life will be examined. Information polices from the higher-level and local level organizations influence the course syllabi. Of the syllabi considered, the topics of academic integrity and plagiarism, communication, and student privacy and information security were the most consistent throughout. Academic integrity and plagiarism policies referenced a mix of local level and higher-level policies as well as there being no mention of them. Policies regarding communication showed to be more informal, where student privacy and information security were formal among the syllabi. The syllabi containing policies concerning communication, whether it was between the instructor and student or through Blackboard, did not reference any specific polices for Wayne State University, the School of Library and Information Science, or the WSU Library System. Moreover, the syllabi containing the subject of student privacy and information security referenced the Family Education Rights and Privacy Act. Regardless of informal or formal policy structures, these information policies affect flow of information, which thus affects the student’s academic progress. See Appendix C for comparison between information policies among course syllabi. Wayne State University and the School of Library and Information Science provide clear and succinct policies to their students. However, improvements to course syllabi can be made to better assist in the dissemination of information as well as the student’s understanding of information policies. First, more can be done to include information about what instructors do with the student’s information while the course is in session and when the course is completed. ANALYZING INFORMATION POLICIES 7 The section pertaining to student privacy and information security should include an explanation concerning this issue. Secondly, syllabi should also include policies regarding the use of technology and resources obtained from the online databases. In particular, the syllabi should reference the Acceptable Use of Technology Resources and the Acceptable Use of Electronic Resources provided Wayne State University and the WSU Library System. It is important the student know the protocol of using course material provided by the WSU Library System and resources instructors post in Blackboard. Lastly, the syllabi should be congruent between the different courses. Two of the twelve syllabi consulted listed no policies about academic integrity and plagiarism, communication, and student privacy and information security. For instance, the School of Library and Information Science could develop an information policy outlining the requirements for what should be included in course syllabi. By considering these improvements to course syllabi, the student can have more knowledge about his or her information security and personal privacy as well as a better understanding of what is expected of them and of their instructors and university. In conclusion, the development of information policies is a vital, ongoing, and changing process; and Wayne State University along with the WSU Library System and the School of Library and Information Science have significant roles. Starting at the higher-level and flowing through the local levels and finally ending in the course syllabi, information policies affect the student and his or her academic progress through the flow of information. Illustrating this, Jaeger (2007) states “information access is of utmost importance in democratic societies; without sufficient access to information, political discourse and democratic dialogue are hampered.” By establishing well-defined information policies, Wayne State University and its students are presented with better access to networks of communication. ANALYZING INFORMATION POLICIES 8 Appendix A: Information Policy Relational Diagram *to view online (click) ANALYZING INFORMATION POLICIES 9 Appendix B: Examples of Local Policies The below table lists the policies referenced within the local levels such as WSU Library System and the School of Library and Information Science and at the higher, university level. Some policies given at the lower level may be higher-level policies. The higher-level policies that are mentioned at the lower level are highlighted in blue. In addition, there are three policies referenced that have been designed by other institutions such as government offices and thirdparty network technologies. These are highlighted in orange. Lastly, the missing relationships between the local and higher levels are indicated in red. Local level Higher level Policies WSU Library System Due Process Policy (http://lib.wayne.edu/info/po licies/due_process.php) Code of Conduct (http://www.doso.wayne.edu /assets/codeofconduct.pdf) Academic Integrity & Plagiarism Student Privacy and Information Security Privacy Policy (http://lib.wayne.edu/info/polici es/privacy.php) The Library Privacy Act (http://www.legislature.mi.gov) Family Education Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA) School of Library and Information Science SLIS Policies (http://students.slis.wayne.ed u/policies/academic_integrity .php) Graduate Bulletin (http://www.bulletins.wayne. edu/gbk-output/index.html) Code of Conduct (http://www.doso.wayne.edu/ assets/codeofconduct.pdf) Plagiarism Quiz (http://students.slis.wayne.ed u/policies/plagiarismquiz.php) Family Education Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA) Wayne State University Policies (http://www.doso.wayne.edu/ academic-integrity.html) Graduate Bulletin (http://www.bulletins.wayne. edu/gbk-output/index.html) Code of Conduct (http://www.doso.wayne.edu/ assets/codeofconduct.pdf) Plagiarism Quiz Confidential Information Policy (http://fisopsprocs.wayne.edu /policy/) Freedom of Information Act (http://fisopsprocs.wayne.edu /policy/) Privacy of Academic Records (http://reg.wayne.edu/faculty/ privacy.php) Family Education Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA) (http://www.ed.gov/policy/ge n/guid/fpco/ferpa/index.html) ANALYZING INFORMATION POLICIES Student Progress and Grading Technology & Information Access Acceptable Use of Electronic Resources (http://lib.wayne.edu/info/polici es/eresources.php) Acceptable Use of Technology Resources (http://wayne.edu/policies/acce ptable-use.php) Borrowing Privileges (http://lib.wayne.edu/services/b orrowing/) Digital Media Copyright Guidelines for Faculty & Staff (http://lib.wayne.edu/info/polici es/copyright_guidelines.php) Copyright Guidelines for Posting Documents to Blackboard (http://lib.wayne.edu/info/polici es/copyright_blackboard.php) 10 SLIS Polices – Withdrawal, dismissal; Incomplete, change, or appeal of grades (http://students.slis.wayne.ed u/policies/academic_progres s.php) Code of Conduct (http://www.doso.wayne.edu /assets/codeofconduct.pdf) Readmission Policy (http://students.slis.wayne.ed u/policies/readmission.php) Student Academic Review (http://students.slis.wayne.ed u/policies/sar.php) Online Searching (http://students.slis.wayne.ed u/policies/online_searching.p hp) Acceptable Use of Technology Resources (http://www.wayne.edu/polic ies/acceptable-use.php) E-Portfolio Technology Support (http://students.slis.wayne.ed u/eportfolios/technologysupport.php) Acceptable Use Policy (http://students.slis.wayne.ed u/technology/use-policy.php) Copyright Guidelines for Posting Documents to Blackboard Code of Conduct (http://www.doso.wayne.edu /assets/codeofconduct.pdf) Course Policy Notes (http://reg.wayne.edu/student s/policies.php) Acceptable Use of Technology Resources (http://www.wayne.edu/polic ies/acceptable-use.php) Responsibility for WSU’s Network Infrastructure (http://fisopsprocs.wayne.edu /policy/) Information Technology System Policy (http://fisopsprocs.wayne.edu /policy/) Strong Password Standards (http://www.computing.wayn e.edu/about/strong-passwordstandard.php) Copying of Computer Software Programs (http://www.computing.wayn e.edu/policies/copypolicy.ph p) Merit Acceptable Use Policy (http://www.merit.edu/policie s/acceptable_use.php) Wayne State HEOA Copyright Protection Plan (http://computing.wayne.edu/ policies/heoa_plan.php) Acceptable Use of Electronic Resources ANALYZING INFORMATION POLICIES 11 Appendix C: Examples of Information Policies within Course Syllabi The examples of information policies are displayed several ways within the course syllabi. Several syllabi reference policies of the School of Library and Information Science (SLIS) and others reference policies of Wayne State University (WSU). Hyperlinks to these policies are provided along with a summary describing the policy. Other instructors do not reference policies from either the SLIS or WSU, but rather develop his or her own policy. These differences were displayed among academic integrity and plagiarism, communication, ePortfolio, student privacy and information security, student responsibilities, student disabilities, and student progress and grading policies. The example below demonstrates the differences between academic integrity and plagiarism policies among course syllabi. Some reference and include information policies of the School of Library and Information Science, Wayne State University, and the instructor’s own creation. Example 1a: Syllabus referencing both SLIS and WSU policies Academic Integrity & Plagiarism Plagiarism is considered scholastic dishonesty and is not tolerated by the School of Library and Information Science or the University. Cutting and pasting information from electronic resources without citing sources is plagiarism. Carefully quote your sources, giving the context of statements and cite the source according to the APA style manual. Plagiarized assignments will result in an “F” for the course and may be grounds for disciplinary action. For more information, refer to the WSU SLIS website, http://www.slis.wayne.edu/about/policies.php. Read the university’s statement on academic integrity at: http://tinyurl.com/96aav43 and the underlying Code of Conduct http://www.doso.wayne.edu/codeofconduct.pdf, so there is no doubt whatsoever in your mind what academic integrity is. Under no circumstances will your ignorance of these standards, policies and scholarly practices be accepted as a defense for cheating, falsification, fabrication, or plagiarism. Plagiarism Quiz Plagiarism occurs, not only as a result of conscious cheating, but often because of misunderstandings about what really constitutes plagiarism. Take the School quiz to learn more about plagiarism and how to avoid it. Go to: http://slis.wayne.edu/plagiarism-quiz.phpto take the quiz. (Maatta-Smith, 2012) ANALYZING INFORMATION POLICIES 12 Example 1b: Syllabus referencing SLIS policy Academic Integrity For explanations of academic issues such as attendance, plagiarism, incompletes, withdrawals, please consult the SLIS Program Policies: http://slis.wayne.edu/policies.php (Charbonneau, 2013 and Walter, 2013a) Example 1c: Policy referencing WSU policy Academic Integrity Academic work submitted by a graduate student for graduate credit is assumed to be of her/his own creation, and, if found not to be, will constitute cause for the student’s dismissal from the School” (Wayne State University Graduate Bulletin). Plagiarism is generally defined as claiming someone else’s ideas, words or information. It constitutes intellectual theft. Plagiarism can be avoided by footnoting any data, language, or ideas not of one’s own creation. Paraphrasing or rewording of another’s work without appropriate credit is also plagiarism. Similarly, plagiarism violates a student’s responsibilities when a student purchases or otherwise acquires work done by another and submits it as one’s own. Such behavior constitutes fraud, or cheating, and will result in disciplinary action. A related issue arises when a student takes a previously submitted course assignment and, making few or no changes, submits that assignment as part of the requirement for another course. This ethical violation of the student’s responsibility to submit fresh, original work for each assignment will also be construed as plagiarism. Discovery of any such practices will result in disciplinary action. (Lorenzen, 2013) Example 1d: Instructor’s own creation Academic Integrity You are being encouraged to grow intellectually and to become responsible citizens in our complex society. In order to develop your skills and talents, you will be asked to do research, write papers, prepare presentations, and work individually as well as in teams. Academic dishonesty undermines your intellectual growth. Therefore, violations of the code of academic honesty will not be tolerated. Academic dishonesty is defined as “the giving, taking, or presentation of information or material by a student with the intent of unethically or fraudulently aiding oneself or another on any work which is to be considered in the determination of a grade or the completion of academic requirements.” A student shall be in violation of the academic honesty policy if he / she: 1. Presents the work of others as his / her own, 2. Does the work for another individual in a situation in which that the individual is expected to perform his/her own work, or 3. Offers false data in support of required course work. The act of submitting work for evaluation or to meet a requirement is regarded as assurance that the work is the result of the student’s own thought and study, produced without assistance and stated in that student’s own words (except where quotation, references, or footnotes acknowledge the use of other sources). Students who are in doubt regarding any matter related to the standards ANALYZING INFORMATION POLICIES 13 of academic integrity in this course should consult with the instructor before presenting work. Submitting work that is not your own will result, at a minimum, in a zero score for the assignment and a request to immediately drop the course. (Heinrichs, 2013 and Zhang, 2013) Another significant difference between course syllabi is the Communication and Blackboard information policies. All mention a preferred method of contact the student should use in communicating with the instructor as well as etiquette regarding commenting and posting on discussion boards. Two syllabi reference an external link not associated with the university for “netiquette” behaviors for posting online. These polices tend to be informal, where these may not necessarily be directly stated. Below is an example between three syllabus communication policies. Example 2a: Communication Email: Email is the best way to contact me. I will check email Monday-Friday between 6:00 PM and 9:00 PM. I can’t guarantee that I will check email on weekends. You can email me at av8728@wayne.edu. If your email address does not contain your Access ID, then please include it in your email. Please make subject lines specific, for instance “HTML Assignment Question”, not just “HTML” or “Question”. If you change topics during a string of emails, please indicate that in the Subject line “Lecture 2 Section 4 Question WAS Re: HTML Assignment Question”. Course announcements, changes and updates will be posted in Blackboard. I may also send out important announcements through e-mail. You are expected to check, at least five times a week, the course Website in Blackboard and your Wayne State e-mail account [you may have it forwarded to another e-mail account that is checked regularly]. Phone: I will be receiving a phone number from the university and will post that when it is available. That phone number will lead directly to voicemail and I will check those voicemails Monday-Friday between 6:00 PM EST and 9:00 PM EST Virtual Office Hours: I will post a link to our Adobe meeting space in Blackboard. Office hours start at 7:30 PM EST on Wednesdays. If I do not have anyone in office hours by 8:00 PM EST, I will leave for the evening. If you can’t make office hours, I’m happy to schedule an appointment. (Ayar-Illichman, 2012) ANALYZING INFORMATION POLICIES 14 Example 2b: Blackboard Discussion Use Policies Discussion boards will be available for general and specific topics. The discussion boards are intended to be a place for questions and discussion in connection with this course and other course-related topics. Above all else, posters are to conduct themselves in a civil manner, and treat fellow students with respect. For more information on netiquette rules please visit: http://www.albion.com/netiquette/. I will answer your questions posted on the discussion board as often as I can. Since I travel internationally, due to time zone difference and Internet availability, I might not be able to be very prompt with my answers. This is an asynchronous class. E-mail Communication You must activate and use your Wayne State University account. I will not answer e-mails received from private accounts such as “crazydog@yahoo.com.” Post your questions in the Blackboard discussion board rather than sending them to me via e-mail. This way the entire class will benefit from having your questions answered. If you need to contact your instructor via e-mail, in the subject heading of your e-mail use LIS 6120—xxx (section number). Don’t forget to sign your messages with your full name. Please make sure your WSU Inbox has enough capacity to receive messages during the semester. One point will be deducted from the final grade for each message sent by the instructor to your account that bounces back as undeliverable because of ‘over quota.’ Please refrain from inviting faculty to join you on social media networks. (Anghelescu, 2012) Example 2c: (Walster, 2013b) However different the representation and content of the information policies between the course syllabi, the “Student Privacy and Information Security” policy is the most congruent among them. Of the twelve syllabi consulted, only two did not include this section. The rest all ANALYZING INFORMATION POLICIES 15 referenced the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA) and provided the same information. Example 3: Student Privacy and Information Security SLIS follows all WSU policies and procedures regarding student privacy and security as outlined by the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA)--a federal mandate: http://reg.wayne.edu/students/privacy.php (Anghelescu, 2012; Ayar-Illichman, 2012; Biggers, 2013; Charbonneau, 2013; Heinrichs, 2013; Lorenzen, 2013; Maatta-Smith, 2012; Walster 2013a, 2013b; and Zhang, 2013) Lastly, there are information polices that are not included within certain syllabi but should be. After reviewing the syllabi from previous classes, two syllabi lacked significant areas of information policies. Those missing from the syllabi are: 1. Academic integrity and plagiarism, 2. Student privacy and information security, 3. Student progress and grading, and 4. Communication. These four polices are essential to include in course syllabi. ANALYZING INFORMATION POLICIES 16 References Anghelescu, H. (2012). Syllabus for LIS 6120 Access to Information. (Available from the Wayne State University School of Library and Information Science, 106 Kresge Library, Detroit, MI 48202) Ayar-Illichman, C. (2012). Syllabus for LIS 6080 Information Technology. (Available from the Wayne State University School of Library and Information Science, 106 Kresge Library, Detroit, MI 48202) Biggers, A. (2013). Syllabus for LIS 7490 Competitive Intelligence and Data Analytics. (Available from the Wayne State University School of Library and Information Science, 106 Kresge Library, Detroit, MI 48202) Charbonneau, D. (2013). Syllabus for LIS 7620 Health Informatics and E-Science. (Available from the Wayne State University School of Library and Information Science, 106 Kresge Library, Detroit, MI 48202) Heinrichs, J. (2013). Syllabus for LIS 7410 Software Productivity Tools for Information Professionals. (Available from the Wayne State University School of Library and Information Science, 106 Kresge Library, Detroit, MI 48202) Jaeger, P. (2007). Information policy, information access, and democratic participation: The national and international implications of the Bush administration’s information politics. Government Information Quarterly, 24(4), 840-859. doi:10.1016/j.giq.2007.01.004 Lorenzen, M. (2013). Syllabus for LIS 7040 Library Administration and Management. (Available from the Wayne State University School of Library and Information Science, 106 Kresge Library, Detroit, MI 48202) ANALYZING INFORMATION POLICIES 17 Maatta-Smith, S. (2012). Syllabus for LIS 6010 Introduction to the Information Profession. (Available from the Wayne State University School of Library and Information Science, 106 Kresge Library, Detroit, MI 48202) Maxwell, T. A. (2003). Toward a model of information policy analysis: Speech as an illustrative example. First Monday, 8 (6), n.p. Retrieved from http://firstmonday.org/htbin/cgiwrap/bin/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/1060/980 Orna, E. (2008). Information policies: Yesterday, today, tomorrow. Journal Of Information Science, 34(4), 547-565. doi:10.1177/0165551508092256 Walster, D. (2013a). Syllabus for LIS 7996 Research in Library and Information Science. (Available from the Wayne State University School of Library and Information Science, 106 Kresge Library, Detroit, MI 48202) Walster, D. (2013b). Syllabus for LIS 8000 Information Policy. (Available from the Wayne State University School of Library and Information Science, 106 Kresge Library, Detroit, MI 48202) What is Information Policy?. (1998, February 1). Vancouver Community Network - The regional free NET - Home. Retrieved from http://www.vcn.bc.ca/bcla-ip/committee/broch95.html Zhang, X. (2013). Syllabus for LIS 7420 Client-Based Web Site Development. (Available from the Wayne State University School of Library and Information Science, 106 Kresge Library, Detroit, MI 48202)