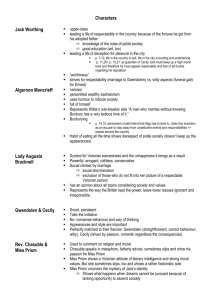

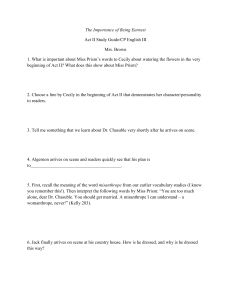

Jack - Canton Local Schools

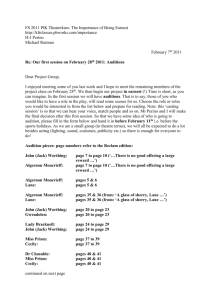

advertisement