This is an introduction to some of the techniques of poetry

advertisement

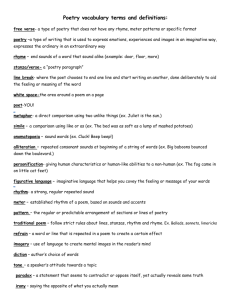

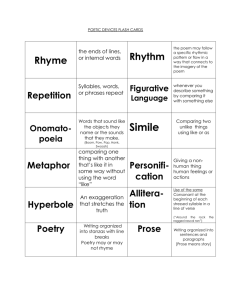

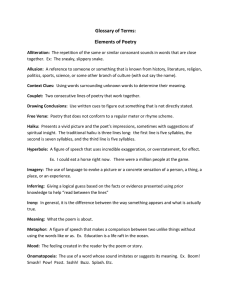

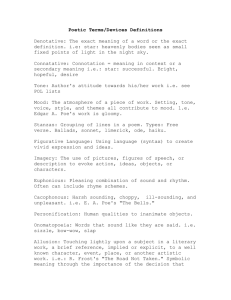

This is an introduction to some of the techniques of poetry which you need to understand to be able to complete the Textual Analysis NAB of the Higher course. Many of these techniques will or should be familiar to you from Standard Grade: others might be new. It is not just a question of identifying the techniques, you must also be able to comment on their effect, and evaluate how effective they are. • Although many of the techniques detailed below also apply to other forms of literature (esp. plays, some of which are written in verse anyway), it is the case that poetry is a particularly condensed form of communication in which not only the meaning of language, but also its power of suggestion, its sound and even its visual appearance on the page can come into play. • Most poems do not tell a story as such but describe a person or a scene or an incident, and attempt to relate that to some general principle or moral. • • • • • • First step The first thing to do when you are confronted with a poem is to try and get the general drift. If the poem is worthwhile, you will not understand everything (or even very much) at first reading. You must then ask yourself certain questions: Is the poem about a person or a place or an incident, or a combination, or none of these? What can you understand of what is being said? Who is the narrator? (first/third person) Read the poem aloud to yourself: how does it sound? What is the mood (tone ) of the poem- serious, humorous, tragic ? does it change? how can you tell? Now it is time to look more closely at the language of the poem Imagery • Imagery is any attempt to create a mental picture in words. “He was tall with fair hair” is an image because it gives you a mental image of someone’s appearance. • In poetry, however, imagery is usually an attempt to compare the thing being described with something else to make the description more vivid. • If the comparison is straightforward, using like or as, it is known as a simile. Coleridge describes a becalmed ship thus: As idle as a painted ship Upon a painted ocean. • This is a straightforward comparison: the ship is so still it is like a painting, although the repetition of “painted” lends emphasis to the image. Often, though, the comparison is more implicit- you have to look harder for it. An implicit comparison is known as a metaphor: Any expression which should not be taken literally is metaphorical. The following extract by Wilfred Owen describes soldiers returning from the trenches in World War 1: Bent double, like old beggars under sacks Knock-kneed, coughing like hags, we cursed through sludge, Till on the haunting flares we turned our backs, And towards our distant rest began to trudge. Men marched asleep; many had lost their boots, But limped on, blood-shod; all went lame,all blind, Drunk with fatigue, deaf even to the hoots, Of gas-shells dropping softly behind. • Here, Owen begins with a simile- like old beggars but the imagery is continued throughout in words such as coughing, cursed, limped, lame, blind, drunk, deaf, to create, in a extended metaphor (A comparison between two unlike things that continues throughout a series of sentences in a paragraph or lines in a poem). , the image of young fit men as old decrepit down-and-outs, to show what their time in the trenches has done to them. Word choice • When you read a line of poetry, you should keep in mind the notion of paradigmatic choice: Simply, this means that every time a poet uses a word, he has chosen it from the whole supply of words which would have done in that place: in the extract above, for example, Owen uses “trudge” when walk, shamble, stagger or several other words would have done. Your job is to say “Why that word?” Was it just so that he could make a rhyme, or was there another reason? • There are a number of possible reasons for choosing particular words: Denotation and Connotation • As poets are trying to say a lot in a small space, they often choose words or expressions which carry ideas or associations along with them. The denotation of a word is the “dictionary” definition it has, its meaning. The connotations of a word are its associated ideas, the things that come to mind when you hear the word. For example: • “Rolls-Royce” denotes a large car, but its connotations are things like luxury, film stars, royalty, money, bad taste and so on. • “Massage parlour” denotes a place where you can get a massage; its connotations are of prostitution, sleaze, middle-aged men etc. • Ask yourself-what connotations does that word have? Ambiguity • If a word is ambiguous it has more than one meaning or its meaning is unclear. Normally, we try to avoid this and say what we mean. However, poets often use it on purpose because they mean to say more than one thing at once. For example, Philip Larkin entitled one of his poems Church Going. On one level, the poem is about someone visiting a church, so the title fits; however, on a deeper level, the poem is about how the Church is disappearing or losing its meaningthe word Going means both visiting and disappearing. • Look at the phrase blood-shod in the Owen extract: it literally means “shoed with blood” because the soldiers had no boots and their feet were cut, but see how it also resembles the words bloodshed, which indicates what the men have just been through, and bloodshot, to suggest their appearance. Suggestion/ Inference • To take things a step further, often the message or theme or gist of a poem is not stated at all, but merely suggested or implied. It is up to the reader to work out what the poem is saying above and beyond what is explicitly stated. We call this process of working out inference, or inferring. To see how it works, look at the poem A Study of Reading Habits. • Inference is an extreme form of what we do whenever we read- we bring our own skill, judgement and experience to the text and combine it with that of the writer. Sound Effects • Poems are meant to be read aloud. Not only the intellectual meaning, but also the sound of the work is important, therefore poets make use of several techniques to do with the sounds of words. One of the most common of these is Repetition • You will often find repeated words or phrases in a poem. Sometimes this is just for emphasis. In the Snack Bar by Edwin Morgan describes the narrator taking a blind and handicapped man downstairs to the toilet: • And slowly we go down, and slowly we go down. • Here Morgan is merely underlining how difficult it is for the man to descend the stairs. But repetition can do more. The fuller version of Coleridge’s verse about the becalmed ship reads: Day after day, day after day, We sat, nor rest nor motion, As idle as a painted ship, Upon a painted ocean Here the repetition of “day after day” gives a sense of weariness as felt by the crew of the ship. Similarly, Macbeth’s “Tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow” creates a feeling of futility and pointlessness. Long and Short vowels • The vowels a e i o u can each be said two ways. The Short pronunciation is: • • • • • a as in hat e as in fed i as in bin o as in pot u as in fun The Long pronunciation is: a as in hate e as in here i as in fine o as in pole u as in duty • There are variations on this: aw and ow are long sounds, for example. Generally, long sounds are used to create a slow feeling, a lack of urgency, relaxation. Short sounds are used to create a feeling of speed, urgency, action. So “day after day, day after day” seems very slow and calm, as it would have done to those on the ship. Similarly “And slowly we go down...” Onomatopoeia • A big word for a simple concept. Some words in English sound like their meaning-thud, bang, crash, tinkle, splash etc. Poets can take this a step further by deliberately using groups of sounds to imitate the sound of what they are describing. Coleridge again, same poem, same voyage, different weather: The fair breeze blew, the white foam flew, The furrow followed free. We were the first that ever burst, Into that silent sea. • Here, all the f and s sounds actually create the sound of the sea foaming as the ship crashes through the waves. Similarly, the last two lines of the extract from Owen: ...deaf even to the hoots • Of gas-sh ells dropping s oftly behind. • The s sounds here mimic the hissing of the poison gas. Rhyme • As you know, rhyme is when words at the end of a line of poetry finish with similar or identical sounds. In previous centuries, nearly all poetry rhymed according to certain patterns. In the twentieth century, rhyme is less, but still, common. • The use of rhyme has historical origins which we need not go into here. However, knowing how to spot a “rhyme scheme” and also to detect any variations in it can alert you to what the poet is trying to do. Exercise • Look at “Long Distance” by Tony Harrison. • How does the rhyme scheme draw your attention to the poet’s purpose? • • • • How to annotate a rhyme scheme. Give the first line of the poem the letter A. Any later line which rhymes with line 1 should also be given letter A. Give the second line the letter B (unless it rhymes with line 1). Any later line which rhymes with line 2 should be given the letter B. Examples. Tam O’Shanter When chapman billies leave the street And drouthy neibours neibours meet As market days are wearing late And folk begin to tak the gate A A B B Miss Gee Let me tell you a little story About Miss Edith Gee She lived in Clevedon Terrace At number 83 A B C B The Walrus and the Carpenter The sun was shining on the sea Shining with all his might He did his very best to make The billows smooth and bright And this was odd because it was The middle of the night A B C B D B Half- rhyme (or pararhyme). • Half rhyme is where there is some sound resemblance between words, but not a full rhyme. In full rhyme, the vowel sound and final consonant sound (if there is one) are normally the same, but the initial consonants are different. For example: mask and task are full rhymes. • With half rhymes, the consonants are often nearly the same, but the vowel sounds are different: mask and musk are half-rhymes. • For some reason, half-rhymes are almost always used to denote depression, disillusionment, despair. They are particularly effective when the rest of the poem has full rhyme or none at all. Look at the following poem from World War I by Wilfred Owen: sketch out the rhyme scheme and comment on the tone. Futility Move him into the sun,Gently its touch awoke him once, At home, whispering of fields unsown. Always it woke him, even in France, Until this morning and this snow. If anything might rouse him now The kind old sun will know. Think how it wakes the seeds,Woke, once, the clays of a cold star. Are limbs, so dear achieved, are sides, Full-nerved, - still warm, - too hard to stir? - O what made fatuous sunbeams toil To break earth’s sleep at all? • This next poem, also from World War 1, needs a knowledge of the story from the Bible of Abraham and Isaac. Comment on the rhyme scheme here. The Parable of the Old Man and the Young. So Abram rose, and clave the wood, and went And took the fire with him and a knife. And as they sojourned both of them together, Isaac the first born spake and said, My Father, Behold the preparations, fire and iron, But where the lamb for this burnt offering? Then Abram bound the youth with belts and straps, And builded parapets and trenches there, And stretched forth the knife to slay his son. When lo! an angel called him out of heaven, Saying, lay not thy hand upon the lad, Neither do anything to him. Behold, A ram caught in a thicket by its horns; Offer the Ram of Pride instead of him. But the old man would not so, but slew his son, And half the seed of Europe, one by one. • • • • • • Rhythm and Metre Rhythm is present in all spoken language: if we did not speak with rhythm, we would sound like “interactive” computers. As well as polysyllabic words having stressed and unstressed syllables, sentences have stresses also, in order to point up meaning. What is the difference between the following: I am going to London. I am going to London. I am going to London. Rhythm in poetry refers to the sound of the lines: quick or slow, smooth or jerky. The rhythm can be achieved by various means: Punctuation • A lot of punctuation, especially in the middle of lines, slows things down, makes the lines sound jerky. • Less or no punctuation speeds up the sound of lines. • Remember Dulce et Decorum est agan: Bent double, like old beggars under sacks, Knock-kneed, coughing like hags, we cursed through sludge... • In the following stanza, there is a gas attack, and panic ensues: Fitting the clumsy helmets just in time, But someone still was yelling out and stumbling And floundering like a man in fire or lime... • The lack of punctuation in the second segment speeds up the whole sound, just as the soldiers speeded up. Word choice • Short vowelled words sound quick; long vowelled words sound slow. • Two syllable words, for some reason, sound much sharper than three syllable words. • Macbeth’s “Tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow” sounds infinitely wearying and despairing. If he had said “Tonight and tonight and tonight” it wouldn’t have been the same at all. Enjambment • This is defined as “the running on of a sentence from one line of verse to another” but it’s actually more than that. Sentences run from one line to another all the time. Enjambment is more when a closely related segment of a sentence runs into another line. Look at this example from Larkin’s “Next Please”: Flagged and the figurehead with golden tits Arching our way, it never anchors, it’s No sooner present than it turns to past. Right to the last, • The it’s at the end of line 2 definitely belongs with line 3: the enjambment creates an unnatural pause meant to mimic the sense of anticipation we have at the approach of a big event. • What, then, does the rhythm of line 3 suggest, and how? Metre • Metre is a poetic term meaning that rhythm has been used in a regular way, according to some pattern. • There are a wide variety of metres. Here is “A Study of Reading Habits” again. • When getting my nose in a book- 3 stresses • Cured most things short of school- 3 stresses • It was worth ruining my eyes- 3 stresses • To know I could still keep cool- 3 stresses • The pattern here is quite loose: the stresses are not regular on syllables. However, the number of stresses or beats to the line is 3 on each occasion. • An iamb is a pair of syllables, the first one unstressed, the second stressed. It is a very common means of constructing poetry, giving a regular beat to verse. Here is one example: If seven maids with seven mops - 4 stresses Swept it for half a year - 3 stresses Do you suppose, the walrus said - 4 stresses That they could get it clear? - 3 stresses • Lines 1 and 3 are called iambic tetrameter (tetrameans four). • Lines 2 and 4 are called iambic trimeter (tri- means three). • Shakespeare usually writes in iambic pentameter (penta- means five). Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day Thou art more lovely and more temperate Rough winds do shake the darling buds of May... • Iambic pentameter is said to be popular because it imitates the sound of the human heartbeat.If Shakespeare wants to draw your attention to something important, his verse will skip a beat. Mood and Tone • These two terms are now just about interchangeable. They mean the emotional state of a piece of poetry, what the poet was feeling, what we are meant to feel when we read the poem. • Here are two contrasting lines: oy it was on that morn to be alive! and Dark, dark, dark, we all go into the dark. Contrasting emotions, easy to spot. Two more difficult ones from WW1 again. In Flanders Fields In Flanders fields the poppies blow Between the crosses row on row That mark our place; and in the sky The larks, still bravely singing, fly Scarce heard amid the guns below. We are the dead. Short days ago We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow, Loved and were loved, and now we lie In Flanders fields. Take up our quarrel with the foe: To you from failing hands we throw The torch... Does it matter? Does it matter?- losing your legs... For people will always be kind, And you need not show that you mind When the others come in after hunting To gobble their muffins and eggs. Does it matter? - losing your sight?... There’s such splendid work for the blind; And people will always be kind, As you sit on the terrace remembering And turning your face to the light. Do they matter?- those dreams from the pit?... You can drink and forget and be glad, And people won’t say that you’re mad; For they’ll know you’ve fought for your country And no-one will worry a bit. Same subject matter- casualties of war- very different attitude. What? How is tone and mood achieved: here; in general. See on for examples! • • • • SYLLABLES, STRESS AND RHYTHM A syllable is one separate sound of speech. Cat is a one-syllable word because it is only one sound. Begin is a two-syllable word: be-gin Acrobat is a three-syllable word: ac-ro-bat Electrical is a four-syllable word: e-lec-tric-al...and so on. Exercise 1 • a. How many syllables do the following words have: • 1. thorough 2. apache 3. kangaroo 4. rhinoceros 5. rhythmical • 6. disciplinarian 7. gardener 8. nevertheless 9. borough 10. mathematician • 11. polyphiloprogenitive. • b. Make your own list of 1,2,3,4,5 syllable words. STRESS • If you have ever heard a voice synthesiser, you will know what people would sound like if they did not use stress- their voices would be flat and monotonous. • All people when talking stress syllables and wordsthat is, they say some louder than others. Take for example EVENTUAL • If you say this to yourself, you will realise that the syllable -VEN- is said louder than the other syllables. It is the stressed syllable in the word. To show this, you could write the word as EVENTUAL Exercise 2 • Write these words out, marking the stressed syllable • 1. gardener 2. beautician 3. continent 4. continental 5. desert 6. dessert 7. television 8. crocodile 9. library 10. librarian 11. avoid 12. upset (noun) 13. upset (verb)