The Fall of the Great Empires

advertisement

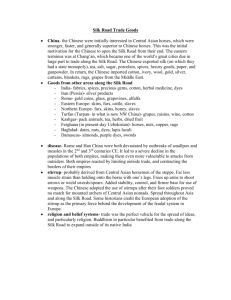

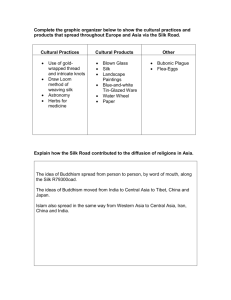

Classical Trade Patterns and Contacts Plus the Fall of the Classical Empires Classical Trade Patterns and Contacts An important change in world history during the Classical period was the expansion of trade networks and communications among the major civilizations. These trade networks were often controlled by nomads who lived in the vast expanses between civilizations or on their outskirts. Classical Trade Patterns and Contacts As a result of these growing networks, more areas of the world were interacting and becoming increasingly dependent on one another. Three large trade networks developed between 300 BCE and 600 CE: the Silk Road, the Indian Ocean trade, and the Saharan trade. The Silk Road The Silk Road: This fabled trade route extended from Xi’an in China to the eastern Mediterranean. It began in the late 2nd century BCE when a Chinese general (Zhang Jian) was exploring the Tarim Basin in central Asia and discovered “heavenly horses” that were superior to any bred in China. The Silk Road This breed of horse was considered so superior that they caused a war (the first known war fought over horses). A Han Chinese army traveled over 6,000 miles to bring these horses back for the emperor (Wu Di). Today they are known as the Akhal teke, and they are still bred by Central-Asian nomads. The Silk Road The “Heavenly Horses” of the Tarim Basin: The Silk Road The Silk Road Over 6,000 years ago silk was a valued fiber for fabric. For many centuries, silk fabric was reserved exclusively for the emperor and his royal family. Gradually silk became available for general use. Farmers paid their taxes in grain and silk. The Silk Road In addition to clothing, silk was used for musical thread, fishing line, bowstrings and paper. Eventually it became one of the main elements of the Chinese economy. The Silk Road Silk farmers raise silkworms, which take about 3-4 weeks to spin a cocoon. Then the cocoons are carefully unwound to a length up to 3,000 ft long. It takes several hundred cocoons to make a single shirt or blouse. The Silk Road The shimmering appearance of silk is due to the triangular prism-like structure of the silk fiber, which allows silk cloth to refract incoming light at different angles, which produces different colors. The Silk Road Emperor Wu Di of the Han Dynasty decided to develop trade with countries to the west, and the building of a road across Asia was his main legacy. It took nearly sixty years of war and construction. The Silk Road Individual merchants rarely traveled from one end to the other (about 5,000 miles); instead they handled long-distance trade in stages. The Chinese had many goods to trade, including their highly prized silk, and with the discovery of the “heavenly horses”, the Chinese now had something that they wanted in return. The Silk Road The Tarim Basin was connected by trade routes to civilizations to the west, and by 100 BCE, Greeks could buy Chinese silks from traders in Mesopotamia, who in turn had traded for the silk with nomads that came from the Tarim Basin. The Silk Road The Silk Road Although the Romans and Chinese probably never actually met, goods made it from one end of the Silk Road to the other, making all the people along the route aware of the presence of others. The Silk Road Traders going west from China carried peaches, oranges, apricots, cinnamon, ginger, cloves, pepper, and other spices as well as silk. The Silk Road Spices were extremely important in classical times. They served as condiments and flavoring agents for food, and also as drugs, anesthetics, aphrodisiacs, perfumes, aromatics, and magical potions. The Silk Road Traders going east carried alfalfa (for horses), grapes, pistachios, sesame, spinach, glassware, and jewelry. The Silk Road Inventions along the route made their way to many people. For example, the stirrup was probably invented in what is today northern Afghanistan, and horsemen in many places realized what an advantage the stirrup gave them in battle, so it quickly spread to faraway China and Europe. The Silk Road The Silk Road was essentially held together by pastoral nomads of Central Asia who supplied animals to transport goods and food/drink needed by caravan parties. For periodic payments by merchants and governments, they provided protection from bandits and raiders. The Silk Road The nomads insured the smooth operation of the trade routes, allowing not only goods to travel, but also ideas, customs, and religions, such as Christianity, Buddhism, Hinduism, and Islam. The Silk Road Biological exchanges were also important, but unintended, consequences of the silk roads. Contagious microbes spread along the trade routes, finding new hosts for infection. Until immunities were acquired, deadly epidemics took a terrible toll in the second and third centuries CE. The most destructive diseases were smallpox, measles, and bubonic plague. The Silk Road Smallpox, Measles, and Bubonic Plague Indian Ocean Maritime Trade The Indian Ocean Maritime System: Water travel from the northern tip of the Red Sea southward goes back to the days of the river valley civilizations. The ancient Egyptians traded with peoples along the southern coast of the Arabian Peninsula. Indian Ocean Maritime Trade During the river valley era, water routes were short and primarily along the coasts. During the classical era, those short routes were connected together to create a network that stretched from China to Africa. Indian Ocean Maritime Trade Like the traders on the Silk Road, most Indian Ocean traders only traveled back and forth along on one of its three legs: 1). southeastern China to Southeast Asia; 2). Southeast Asia to the eastern coast of India; and 3). The western coast of India to the Red Sea and the eastern coast of Africa. Indian Ocean Maritime Trade Indian Ocean Maritime Trade Countless products traveled along the Indian Ocean routes, including ivory from Africa and India; frankincense and myrrh (fragrances) from southern Arabia; pearls from the Persian Gulf; spices from India and SE Asia; and manufactured goods and pottery from China. Indian Ocean Maritime Trade Comparison between the Mediterranean and Indian Ocean: Differences in physical geography shaped different techniques and technologies for water travel during the classical period. The Mediterranean’s calm waters meant sails had to be designed to pick up what little wind they could, so large, square sails were developed. Indian Ocean Maritime Trade The most famous of the ships, the Greek trireme (from the Latin triremis—3 oars), had three tiers of oars operated by 170 rowers. Indian Ocean Maritime Trade A mosaic of a Roman trireme from the Punic wars (battles with Carthage). Indian Ocean Maritime Trade In contrast, sailing on the Indian Ocean had to take into account the strong seasonal monsoon winds that blew in one direction in the spring and the opposite direction during the fall. Indian Ocean ships sailed without oars, and used the lateen sail (roughly triangular with squared off points). Indian Ocean Maritime Trade Lateen sails were more maneuverable through strong winds. Indian Ocean Maritime Trade The boats were small, with planks tied together with palm fiber. Mediterranean sailors nailed their ships together. Indian Ocean Maritime Trade Mediterranean sailors usually stayed close to shore because they could not rely on winds to carry them over the open water. The monsoon winds allowed Indian Ocean sailors to go for long distances across water. Trade Routes Across the Sahara Before the classical era, the vast Saharan desert of northern Africa formed a geographic barrier between the people of Sub-Saharan Africa and those that lived to its north and east. Trade Routes Across the Sahara The introduction of the camel to the area (probably in the 1st century BCE) made it possible to establish trade caravans across the desert. Trade Routes Across the Sahara Camels probably came to the Sahara from Egypt (by way of Arabia), and effective camel saddles were developed to allow trade goods to be carried. Trade Routes Across the Sahara Arabian or dromedary (Arabia or N. Africa). They are faster and can travel more miles in a day than the Bactrian camel. Good in deserts, flat land or rolling hills, they are not good on slippery surfaces. Trade Routes Across the Sahara Bactrian (Central Asia). Bactrian camels are better suited for cold climates with rugged terrain. They have shorter legs and stout bodies and they can walk over slippery surfaces that dromedary camels can't handle. Trade Routes Across the Sahara A major incentive for the Saharan trade was the demand for desert salt, and traders from SubSaharan Africa brought forest products from the south like kola nuts and palm oil to be traded for salt. Trade Routes Across the Sahara Extensive trade routes connected different parts of Sub-Saharan Africa, so that the connection of Eastern Africa to the Indian Ocean trade meant that goods from much of Sub-Saharan Africa could make their way to Asia and the Mediterranean. Many of these trade routes still function today. The Incense Roads There has been an Incense Trade Route for as long as there has been recorded history. As soon as the camel was domesticated, Arab tribes began carrying incense from southern Arabia to the civilizations scattered around the Mediterranean Sea. By the time of King Solomon, the incense route was in full swing, and Solomon reaped rich rewards in the form of taxes from the incense passing into and through his kingdom. The Incense Roads The Incense Roads The records of Babylon and Assyria all mention the incense trade but it wasn't until the Nabataean tribe of Arabs dominated the Incense Road that Europeans took notice. Up until 24 BCE the Nabataeans moved large caravans of frankincense, myrrh and other incenses from southern Arabia and spices from India and beyond to the Mediterranean ports of Gaza and Alexandria. The Incense Roads The Nabataeans carved the famous building of Petra out of solid rock (located in today’s southern Jordan). The Incense Roads The Roman historian Pliny the Elder mentioned that the route took 62 days to traverse from one end of the Incense Road to the other. “Rest stops” were every 20-25 miles. At its height, the Incense Roads moved over 3000 tons of incense each year. Thousands of camels and camel drivers were used. The profits were high, but so were the risks from thieves, sandstorms, and other threats. The Incense Roads The legend of the three Magi (Kings or Wise Men) traveled along the Incense Roads to Bethlehem, bringing frankincense and myrrh. The Incense Roads •Both frankincense and myrrh are derived from the gummy sap that oozes out of the Boswellia and Commiphora trees, when their bark is cut. •The leaking resin is allowed to harden and scraped off the trunk in tear-shaped droplets; it may then be used in its dried form or steamed to yield essential oils. •Both substances are edible and often chewed like gum. The Incense Roads They are also extremely fragrant, particularly when burned, with frankincense giving off a sweet, citrusy scent and myrrh producing a piney, bitter odor. Myrrh oil served as a rejuvenating facial treatment, while frankincense was charred and ground into a power to make the heavy kohl eyeliner Egyptian women famously wore. The Incense Roads Though perhaps best known for their use in incense and ancient rituals, these substances—both of which boast proven antiseptic and inflammatory properties—were once considered effective remedies for everything from toothaches to leprosy. Frankincense and myrrh were components of the holy incense ritually burned in Jerusalem’s sacred temples during ancient times. The Nomads During the classical period, a number of major migrations of pastoral peoples occurred and no one is sure why. Several of these directly impacted the major civilizations (and in the cases of Rome and India, destroyed them). The Nomads The most characteristic feature of pastoral societies was their mobility. Their movements were not aimless wanderings (as is often portrayed); they systematically followed seasonal environmental changes. Nor were nomads homeless; their homes were elaborate felt tents (called gers) that they took with them. The Nomads Pastoral societies didn’t have the wealth for professional armies or bureaucracies. They valued an independent way of life. The Nomads Despite their limited populations, the military potential from the mastery of horseback riding (or camelback) enabled nomadic peoples to wage mounted warfare against much larger, more densely populated civilizations. Virtually the entire male population (and many women) were skilled hunters and warriors. The Nomads The Nomads Practicing the skills necessary for warriors since early childhood, many nomadic tribes extracted wealth through raiding, trading, or extortion from neighboring agricultural societies. The Xiongnu One such large nomadic group were a people known as the Xiongnu, who lived north of China in the Mongolian steppes. Provoked by Chinese penetration of their territory in the 2nd and 3rd centuries BCE, the Xiongnu created a military confederacy that stretched from Manchuria deep into Central Asia. The Xiongnu The Xiongnu Under the leadership of Modun (r. 210-174 BCE), the Xiongnu took fragmented tribes and transformed them into a more centralized and hierarchical political entity. The Xiongnu “All the people who draw the bow have now become one family,” declared Modun. Tribute, exacted from other nomadic peoples and China itself, sustained the Xiongnu. The Xiongnu In the 1st century BCE, a Chinese Confucian scholar described the Xiongnu people as “abandoned by Heaven…in foodless desert wastes, without proper houses, clothed in animal hides, eating their meat uncooked and drinking blood.” The Xiongnu “From the King and downward they all ate the meat of their livestock, and clothed themselves with their skins, which were their only dress. The strong ones ate the fat and choose the best pieces, while the old and weak ate and drank what was left. The strong and robust were held in esteem, while the old and weak were treated with contempt.” Sima Qian, Chinese historian. The Xiongnu The Han tried dealing with the Xiongnu by offering them trading opportunities, buying them off with lavish gifts, contracting marriage alliances with leaders, and waging periodic military campaigns against them. The Xiongnu Even though the Xiongnu would disintegrate under sustained Chinese counterattacks, they created a model that later nomads (like the Turkic and Mongol tribes) would emulate. By the third century CE, the Xiongnu helped hasten the collapse of the weakened Han dynasty, causing China to fall into chaos for several centuries. The Xiongnu As the Han were falling apart, nomadic peoples had a relatively easy time breaching the Great Wall. A succession of “barbarian states” developed in north China. The “barbarian” rulers gradually became Chinese, encouraging intermarriage, adopting Chinese dress and customs, and setting up their courts in a Chinese fashion. The Huns Probably the most famous nomadic warriors of this period were the Huns. During the late 4th century CE, they began an aggressive westward migration from their homeland in central Asia. The Huns might have been motivated to migrate because drought led to competition over grazing lands. The Huns Whatever their motivation, they exploded out of the Russian steppes (descendents of the fabled Scythians) into Europe, settling in modern-day Hun(gary) around 370 CE. Fierce fighters and superb horseman, the Huns struck fear into both the German tribes and the Romans. The Huns Their appearance forced the resident Visigoths, Ostrogoths and other Germanic tribes to move westward and southward and into direct confrontation with the Roman Empire. To the Christian scholar St. Jerome (340420 CE) the Huns “filled the whole earth with slaughter and panic alike as they flitted hither and thither on their swift horses.” The Huns Led by the infamous Attila (406-453 r. 433-453 CE), to the Romans, he was known as the “Scourge of God.” Attila by Delacroix The Huns When he came of age, Attila acquired a vast empire, that stretched through parts of what is now Germany, Russia, Poland, and much of south-eastern Europe. This is a medal cast during the Renaissance that in Latin calls him the “Scourge of God.” The Huns Even though he was extremely wealthy, Attila led a very simple life. In the tradition of nomadic warriors, he drank mare's milk, blood, and ate raw meat. He wore plain clothes and animal skins. His belief system was unknown but he demonstrated little, if any, concern for local religions or Christianity. The Huns As Attila closed in on the Byzantine Empire, the Byzantine emperor (Theodosius II) paid Attila an enormous sum of $$ to leave Byzantium alone (660 lbs of gold/year). The Huns The unsteady peace only lasted a few years as the Huns attacked Persia (but were repelled), so they pressed west and south (into today’s Balkans), destroying virtually everything in their path. From there, the half million+ Hun forces stormed through Austria, Germany, and Gaul (France). The Huns Attila went all the way to the outskirts of Paris (Orleans) before a combined Roman/Visigoth army turned him back (451 CE). Undeterred, he would now focus on Italy. The Huns Setting his sights on Italy, Attila destroyed several Italian cities in Lombardy (452 CE) on his way to Rome. The Huns In a celebrated meeting with Pope Leo I, the Pope begged Attila to spare Rome and withdraw from Italy (which he did – probably because of an epidemic). The Huns Attila died in 453, not on the battlefield, but on the night of his 7th marriage. He got drunk (and he rarely drank), fell to the floor, and died of a bleeding hemorrhage from his nose (he choked on his own blood). The Huns After the death of Attila, the leadership of the Huns fell to his three inadequate sons, who split their empire. The empire ended in 469 CE with the death of Dengizik, the last Hunnish king. The empire of the Huns in Europe withered and disappeared, absorbed into other ethnicities, like Germanic tribes. Germanic Tribes Even though the Huns became less of a force after the death of Attila, they showed the vulnerability of the Romans, and the Germanic groups took full advantage. They spent much of their time fighting each other, behavior the Romans encouraged hoping to keep them weak. Germanic Tribes But by the 4th-5th centuries, they roamed throughout the western Roman provinces without much resistance from Rome. Germanic Tribes Tribal war chiefs began creating their own kingdoms that eventually evolved into the European countries you’re familiar with (the Franks settled in France, the Lombards in Italy, the Angles & Saxons in Britain, the Visigoths in Spain, etc.) The Fall of Rome Rome would finally fall to the Germanic tribes of General Odoacer in 476 CE when he overthrew the last Roman emperor in the West. The Fall of Rome Even though the fall of Rome had been decades in the making, the year 476 is considered a major turning point in the West. By 476, most of what characterized Roman civilization had weakened, declined, or disappeared. The Fall of Rome Any semblance of large-scale centralized power vanished as ineffective emperors were more concerned with pleasure than wise rule. There was social and moral decay and a lack of interest within the elite classes to participate in government. Courtesy and dignity were reduced. Roman dependence on slave labor remained high. The Fall of Rome Disease and warfare reduced the Roman Empire’s population between 25-50%. Land under cultivation contracted, while forests, marshland, and wasteland expanded. Small landowners, facing increased taxes, were often forced to sell their land to the owners of large estates, or latifundia. (great disparities in wealth) The self-sufficiency of the latifundia (estates) lessened the need for central authority and discouraged trade. The Fall of Rome With less trade, urban life diminished and Europe reverted back to a largely rural existence. Rome had been a city of over 1 million people; by the 10th century it had less than 10,000. Rome’s great monumental architecture crumbled from lack of care. The Fall of Rome Long distance trade dried up as Roman roads deteriorated, and money exchange gave way to barter. The Germanic peoples the Romans had long considered barbarians emerged as the dominant peoples of Western Europe (which caused Europe’s center of gravity to move away from the Mediterranean toward the north and west). The Fall of the Gupta By the late 5th century, the Huns were pouring into the Indian subcontinent. Defense against the Huns bankrupted the Gupta treasury, and they collapsed by 600 CE. But the Gupta collapse was far less devastating than that of Rome or Han China. Even though centralized Gupta rulers declined in power, local princes (the Rajput) became more powerful. The Fall of the Gupta Even though political decline occurred as a result of invasions, traditional Indian culture continued (because people cared more about caste and Hinduism). Buddhism declined in India (because it was associated with foreigners), while Hinduism added to its numbers. The next challenge for India’s traditional culture would come during the post-Classical period when Islam arrives. The Fall of the Han The Han dynasty was the first of the great civilizations to go. Its decline began around 100 CE, and many of the causes were similar to Rome’s… Increasingly weak leadership at the top and less interest in Confucian intellectual goals. Courtesy and respect were lessened. Heavy taxes levied on the peasants. Poor harvests. The Fall of the Han Unequal land distribution. Population decline from epidemic diseases. A decline in trade led to declining urban vitality. Pressure from bordering nomadic tribes. These symptoms all led to massive social unrest, as peasants and students protested governmental policies that further impoverished the farmers. The Fall of the Great Empires In the centuries between 200-600 CE, all three of the great civilizations collapsed, at least in part. The period of expansion and integration of large territories was coming to an end. Why? What forces pushed once great societies into decline? Do societies have some kind of common lifespan that pushes them ultimately into aging and decay? The Fall of the Great Empires The western part of the Roman Empire fell, the Han Dynasty ended in disarray, and the Gupta Empire in India fragmented into regions. The fall of these empires marks a great divide in human history. Some common reasons included: The Fall of the Great Empires I. Attacks by nomadic groups: The migration of the Huns from their homeland in Central Asia impacted all three civilizations as they moved east, west, and south. In China and India, attacks by the Huns were directly responsible for the end of those empires. The Fall of the Great Empires The movement of the Huns caused other groups to move out of their way, causing a domino effect that put pressure on Rome. Rome was done in by Germanic invaders from the north. The Fall of the Great Empires II. Serious internal problems: All the empires had trouble maintaining political control over their vast lands, and were ultimately unable to keep their empires together. Less talented leaders were a factor in the decline of all three empires, especially Rome. The Fall of the Great Empires No governments had ever spread their authority over so much territory, and it was inevitable that their sheer size could not be maintained. There was an increased selfishness on the part of the elites, who became less willing to serve in government or military positions. The Fall of the Great Empires The morale of ordinary citizens deteriorated and a sense of helplessness and inevitability to the situation overtook the empires. The Fall of the Great Empires III. The problem of interdependence: The classical civilizations all ended before 600 CE. When one weakened, it impacted them all, as trade routes became vulnerable when imperial armies could no longer protect them or when economic resources necessary for trade were no longer available. The Fall of the Great Empires Pandemic diseases (probably smallpox or measles from India) spread along trade routes, killing thousands that would not have been affected had they not been in contact with others. Modern estimates are that each civilization lost as many as half of their inhabitants during the late classical period. The Fall of the Great Empires Both Rome and China experienced economic and social dislocation brought on by massive death. Labor was difficult to find, and people pulled back from production and trade arrangements that marked the empires at their height. The Fall of the Great Empires Governments had difficulty collecting taxes. Local landlords would compensate for their declining revenues by increasing pressure on local populations. In Rome and China, tension between large landowners and peasants created instability and unrest (Red Eyebrows and Yellow Turbans). The Fall of the Great Empires Despite their similarities, decline and fall had very different consequences for the three civilizations. India and China lost their political unity, but they did not permanently lose their identity as civilizations, and both eventually reorganized into major world powers. The Fall of the Great Empires Only one—(western) Rome—did not retain its identity after it fell. Why? What were the differences? The Roman Empire never regained its former identity and instead fell into many pieces that retained separate orientations. The Fall of the Great Empires The authority of the state dwindled, and localized conditions prevailed. The eastern empire (Byzantium) created by Constantine (r.312-337 CE) maintained many of the institutions and cultural values of Rome. He tried to use Christianity to unify the empire. The Fall of the Great Empires Although early Christians were persecuted, the Emperor Constantine issued the Edict of Milan in 313, which announced the official toleration of Christianity as a faith. Constantine became a Christian (probably on his deathbed), and thereafter all emperors in the East and West (except one) were Christians. The Fall of the Great Empires In 381, the emperor Theodosius made Christianity the official religion of Rome, too late to be the “glue” to hold the crumbling empire together, but in time to preserve Christianity as a faith. The Fall of the Great Empires Justinian (r. 527-565) tried to recapture the glory of Rome but was unsuccessful. He was successful in codifying Roman law (known as Justinian codes). The Fall of the Great Empires Another part of the answer lies in what happened next in the story of world history—political power isn’t the only “glue” that holds a civilization together. In the period before and after 600 CE the most important sources of identity were religious. The Fall of the Great Empires Around the year 600 CE older religions and philosophies (Christianity, Buddhism, Confucianism) grew in influence and transcended political boundaries. An important new religion was on the horizon (Islam). The Fall of the Great Empires Islam was destined to become the force behind one of the largest land expansions in history, a path made easier because it appeared at a time when the old political empires of Rome, China, and India had fallen. The Fall of the Great Empires In this new era of religious unity, Rome fell short. Christianity had become its official religion in the 4th century, too late to be a unifying force for the failing empire. When political and military power failed, nothing was left except crumbling architecture…symbols of the past. The Fall of the Great Empires India was bound together by Hinduism and the intricate caste loyalties that supported it. So the fall of the Gupta had only a limited impact on India’s development. India’s trade worsened a bit but India remained a productive economy. The Fall of the Great Empires The fall of the Gupta was followed by several centuries (nearly a millennia) in which no large empires were created in India except as a result of Muslim (the Mughals), and later, British invasion. The Fall of the Great Empires Confucianism had become such a part of the identity of China, that the fall of Han dynasty was not a fatal blow to its civilization. Chaos did characterize the period, but the Chinese civilization continued and would reassert itself when political stability returned. The Fall of the Great Empires The fall of the Han was followed by 350 years in which the central government didn’t operate. China was divided into regional entities and landlord power increased. In the 6th century CE, a new dynasty, the short-lived Sui, was established. The Fall of the Great Empires With the Sui came the reestablishment of most of the cultural values and institutional workings of the Han. Like India, decline and fall was a relatively temporary setback to the civilization. The Fall of the Great Empires During the classical era, an important change occurred in two of the religions—Christianity and Buddhism—that allowed both to spread to many new areas far from their places of origin. These two religions followed the Silk Road and the Indian Ocean circuit, and their numbers grew greatly. The Fall of the Great Empires Both were transformed into universalizing religions, with core beliefs that transcended cultures and actively recruited new members. As a result, both religions grew tremendously in the years before 600 CE, positioning them to become new sources of societal “glue” that would hold large areas with varying political allegiances together. The Fall of the Great Empires Meanwhile, some important ethnic religions, such as Judaism, the Chinese religions/philosophies (Confucianism and Daoism), and Hinduism created strong bonds among people, but had little emphasis on converting outsiders to their faiths. The Fall of the Great Empires Three durable changes constitute the reason historians use the fall of the great empires to mark the end of the Classical Period and the beginning of the subsequent one. The Fall of the Great Empires I. In most of the “civilized” world, there was less and less emphasis put on empire building or expansion. Societies were less capable, or less interested, in maintaining large, integrated political structures. The Fall of the Great Empires II. The deterioration of this-worldly conditions (especially economic and political decline) pushed people to think about cultural alternatives to the political values of the classical period. The end of the classical period and the beginning of the post-classical period would be marked by greater religious emphasis. The Fall of the Great Empires III. The collapse of the Roman Empire created a permanent division of the Mediterranean world into three different entities: – A. Western Europe – B. Southeastern Europe/northern Middle East – C. North Africa and the rest of the Mediterranean coast. The Fall of the Great Empires The Fall of the Great Empires This division of the Mediterranean had tentatively existed with the Greeks, through Hellenism, and with the Romans. But the collapse of Rome caused the split into three geographic regions to be permanent and this would mark history right up to the present day. The Bantu The Bantu most likely originated in an area south of the Sahara Desert near modern day Nigeria. The Bantu They probably migrated out of their homeland (as early as 2000 BCE) because of desertification, or the expansion of the Sahara Desert that dried out their agricultural lands. They traveled for centuries all over subSaharan Africa, but retained many of their customs, especially language. The Bantu As their language spread, it combined with others, but still retained enough similarity to the original that the family of Bantu languages can still be recognized over most of sub-Saharan Africa. The Bantu Unlike the surges of the Huns and Germanic people, the Bantu migrations were very gradual. By the end of the classical period, the Bantu migrations had introduced agriculture, iron metallurgy, and the Bantu language to most of subSaharan Africa. Polynesians Even though their movements didn’t impact civilizations on the Eurasian mainland, the peopling of the islands of the Pacific Ocean was quite remarkable. Like the Bantu, Polynesian migrations were gradual, but between 1500 BCE and 1000 CE almost all the major islands west of New Guinea were visited, and many were settled. Polynesians Polynesians Polynesians came from mainland Asia and expanded eastward to Fiji, Tonga, and Samoa. They left no written records, so our knowledge relies on archeological evidence, accounts by early European sailors, and oral traditions. Polynesians Their ships were great double canoes that carried a platform between two hulls and large triangular sails that helped them catch and maneuver in ocean winds. Polynesians The distances they traveled were incredibly long, and by the time the Europeans had arrived in the 18th century, the Polynesians had explored and colonized every habitable island in the vast Pacific Ocean.