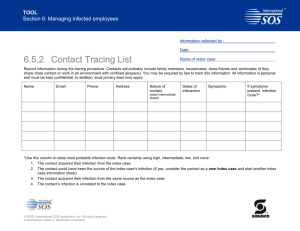

Cough Aerosol Sampling System

advertisement

TB Infection Control:

Principles, Pitfalls, and Priorities

Kevin P. Fennelly, MD, MPH

Interim Director

Division of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine

Center for Emerging & Re-emerging Pathogens

UMDNJ-New Jersey Medical School

fennelkp@umdnj.edu

Objectives

1. To review basic principles underlying TB

transmission and TB Infection Control

policies.

2. To review the recent history of TB Infection

Control.

3. To discuss personal observations and offer

practical solutions to common problems in

TB Infection Control.

Is TB an Occupational Disease of HCWs?

LTBI

Low- & middleincome

countries

63% (33-79%)

High-income

countries

24% (4-46%)

5.8% (0-11%)

1.1% (0.2-12%)

??

1.18 (1.04-1.35)

3.04 (1.62-5.19)

(prevalence)

TB disease

(annual incidence)

TB mortality (inpt)

(PMR)

(outpt)

- Menzies D et al. IJTLD 2007; 11:593

HCW Deaths due to

Nosocomial Transmission of DR-TB

• MDR outbreaks U.S. 1980s-1990s

– 9 HCWs died

• All immunocompromised, 8 with HIV

– Sepkowitz KA, EID 2005

• XDR-TB outbreak, So Africa, 2006

– 52/53 died of unrecognized XDR-TB

• 44/44 tested were HIV+

• Median survival from sputa collection=16 days

• 2 HCWs died; 4 others sought care elsewhere

– Gandhi N, Lancet 2006

Personal Respiratory Protection Against

M. tuberculosis: Contentious Controversy

from Sol Permutt, 2004

Wells-Riley Equation:

Mathematical model of airborne infection

Pr{infection}=C/S=1-e(-Iqpt/Q)

Where

C=# S infected

S=# susceptibles exposed

I = # infectors (# active pulm TB cases)

q = # infectious units produced/hr/Infector

p = pulm ventilation rate/hr/S

t = hours of exposure

Q = room ventilation rate with fresh air

Control Measures are Synergistic & Complementary

Assumptions: Homogenous distribution of infectious

aerosol over 10 hours; uniform susceptibility.

- Fennelly KP & Nardell EA. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 1998; 19;754

Wells-Riley Mathematical Model of Airborne Infection

Probability of MTB Infection:

Isolation Room with 6 ACH:

Infectiousness and Duration of Exposure

1

Risk of MTB Infection

0.9

0.8

0.7

0.6

0.5

1

0.4

10

0.3

100

0.2

1000

0.1

0

0.1

1

10

100

Duration of Exposure (hours)

1000

TB is Spread by Aerosols,

NOT sputum

Particle size* & suspension in air

(* NOT size of bacilli)

• Particle size &

deposition site

–

–

–

–

• Time to fall the height

of a room

100

20

10 – upper airway

1 - 5 – alveolar

deposition

–

–

–

–

10 sec

4 min

17 min

Suspended indefinitely

by room air currents

- Courtesy of Sol Permutt, 2004

*NOT organism size

Six-stage Andersen cascade impactor

Andersen AA. J Bacteriol 1958;76:471.

Cough Aerosol Sampling System

- Fennelly KP et al. Am J Resp Crit Care Med 2004; 169; 604-9

Cough-generated aerosols of Mtb:

Initial Report from Denver, CO

4 of 16 (25%) of SS+ subjects

- Fennelly KP et al. Am J Resp Crit Care Med 2004; 169; 604-9

Variability of Infectiousness in TB:

Epidemiology

Rotterdam, 1967-69: Only 28% of smear

positive patients transmitted infections.

Van Geuns et al. Bull Int Union Tuberc 1975; 50:107

• Case control study 796 U.S. TB cases

– Index cases tended to infect most (or all) or

few (or none) of their contacts

– Snider DE et al. Am Rev Respir Dis 1985; 132:125

• Ability to publish outbreaks suggests that they

are episodic.

Variability of Infectiousness in TB:

Experimental

• All infections attributed to 8 of 61 (13%) patients.

of infections due to one patient with TB laryngitis.

50%

Riley RL et al. Am Rev Respir Dis 1962; 85:511.

• 3 (4%) of 77 patients produced > 73% of the infections in

the guinea pigs.

Sultan L. Am Rev Respir Dis 1967; 95:435.

Recent replication of this model in Peru

118 hospital admissions of 97 HIV-TB coinfected patients

8.5% caused 98% of secondary GP infections

90% due to inadequately treated MDR-TB

Escombe AR et al. PLoS Medicine 2008; 5:e188

Occupational TB

in Sub-Saharan Africa

• Malawi

– 25% mortality

– Harries AD, Tran R Soc Trop Med Hyg 1999; 93: 32

• Ethiopia

• South Africa

• Nigeria

– 32 of 2,173 HCWs

• 15 (47%) as HIV-TB

– Salami AK, Nigerian J Clin Prac 2008; 11: 32

What is the magnitude and variability of infectious

aerosols of M. tuberculosis?

(Can we better identify the most infectious?)

Hypothesis 1: Coughgenerated aerosols of Mtb

can be measured in

resource-limited settings.

Hypothesis 2: Coughgenerated aerosols will be

detected in approximately

25-30% of patients with

PTB.

Cough Aerosol Sampling System

v.2

Frequency Distribution of Cough-generated

Aerosols of M. tuberculosis and

Relation to Sputum Smear Status

31/112 (28%) SS+ subjects

3.5

5

3

4

3

2

1.5

2

1

1

0.5

0

0

1

7

13

19

25

31

37

43

49

55

61

67

73

79

85

91

Subjects Sorted by Aerosol CFU then by Sputum AFB

Aerosol Log 10 CFU

Sputum AFB

97 103 109

Sputum AFB

Aerosol Log CFU

2.5

Cough-generated Aerosols of

M. tuberculosis:

Normalized Particle Sizes

Per Cent CFU

50

40

30

20

10

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

Stage of Andersen Cascade Impactor

Lower limit of size range(µ)

7.0

4.7

3.3

2.1

1.1

0.65

Anatomical deposition: Upper airway -- bronchi -- alveoli

Abstract, ATS International Conference, 2004.

Pitfalls in Administrative Controls

• TB Mortality not prioritized or under

surveillance (i.e., no data collection)

• HIV screening of HCWs not prioritized

– major risk factor for TB disease & death

– HAART now feasible in much of world

– HIV screening advocated for adm’t patients in US

• TB laboratory personnel often not involved in

TB infection control efforts

– Botswana: 1st AFB smear ‘STAT’

• Decisions re: infectiousness falls onto

clinicians with variable expertise

Pitfalls in Environmental Controls

• Little or no engineering expertise and support for

hospitals & HCFs

– No systems of communication / interaction

– Different ‘cultures’ and mind-sets

• TB nurses or administrators subject to sales

pitches from commercial vendors

– UVGI lamps in SANTA facilities

– Mobile air filters in Newark, NJ

• Lack of appreciation of natural ventilation…and

its limitations!

– Low rate of nosocomial infection in Uganda project

– High rate in Tugela Ferry

Pitfalls in Personal Respiratory Protection

• Too much attention paid to ‘masks’ at expense

of administrative and environmental measures

• Rizdon R et al: Renal unit with poor ventilation

• Inappropriate use on patients

• Focus on fit-testing and regulation rather than on

follow up on use in field

• Lack of appreciation that not all respirators

provide the same level of protection

– Need for more protection in high-risk aerosol-inducing

procedures, e.g., bronchoscopies

TB-IC Practices

for Community Programs

• Best administrative control:

– Suspect and separate until diagnosed

– Surveillance of HCWs with TST (and/or IGRAs) and rapid

treatment of LTBI if conversions occur

• Best environmental control: Ventilation

– Do as much as possible outdoors

– Use directional airflow when possible

• Natural breeze or fans: HCW ‘upwind’; patient ‘downwind’

• Personal respiratory protection

– N95 respirators when indoors or very close (procedures)

– Surgical masks on patients to control source

Summary: TB-IC

• Administrative controls most important

component of TB-IC

– ‘Suspect and separate!’

– Prioritize screening HIV in HCWs

• Prioritize good ventilation in all areas

– Back-up in areas with poor ventilation

• Fans, mechanical ventilation, UVGI

• Prioritize personal respiratory protection for

high risk settings, esp where admin and

environ controls limited