Safeguarding and Personalisation – the legal issues

advertisement

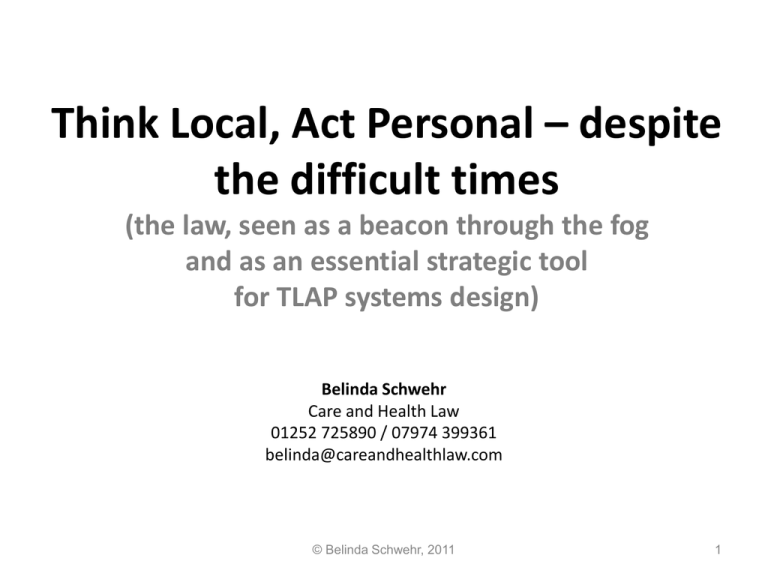

Think Local, Act Personal – despite the difficult times (the law, seen as a beacon through the fog and as an essential strategic tool for TLAP systems design) Belinda Schwehr Care and Health Law 01252 725890 / 07974 399361 belinda@careandhealthlaw.com © Belinda Schwehr, 2011 1 • • • • • • • • How the law has ensured that the public and people with disabilities are not forgotten during policy decisions about raising the FACS threshold higher and higher. How the law has supported the need for providers to be properly consulted, in terms of the market price of services. Universal, preventative and re-ablement services – how the law gives councils clear powers to buy or grant fund services both above and below the line First contact and proper assessment of eligibility – what the law teaches us to avoid, however tempting it might be, to cut corners! And what it says about following government guidance such as FACS and the ordinary residence guidance. Direct payment basics vs managed personal budgets – the law and regs make it clear what they can be spent on, who can exceptionally be employed, who is responsible for what, how an incapacitated person can now have one through a Suitable Person and how public money is protected. Rational funding schemes – how the law has shown that they must be indicative only, and cannot operate on an irrational basis. How does yours shape up? Support planning mistakes – how the law now helps councils exercise ultimate control over the client’s choice of service and deployment arrangement, but ensures their central place in the process Signing off the preferred outcomes with a finalised resource allocation – how the law makes it clear why it crucially matters. Cases I am not going to go on about today .... but which do really matter for modern social care • Pembrokeshire care homes won a JR about not being properly genuinely consulted about a nil percent increase – the case means that all commissioners have got to take all relevant considerations – including the risk to the viability of a market in social care – into account when negotiating prices. • Birmingham lost a case about not doing sufficient impact assessment before raising the FACS threshold to ‘critical’. • But Lancs has won their case because they did it properly. • Manchester, Hillingdon and Cheshire West have lost cases about safeguarding - the last about failing to commission proper services that should clearly have been part of the care plan. The courts are making councils pay the costs of not knowing that they are not In Control when it comes to people’s personal and private lives. © Belinda Schwehr, 2011 3 The most obvious systemic TLAP legal pitfalls to avoid (or exploit!) • The Council denies access to ‘self-directed assessment’ to any individual or client group, as if it had a choice in the matter. All the client need do is establish a right to assessment and ask for a direct payment, and they have to be treated within the law. The law requires that government guidance be followed, unless there’s a very good reason not to! • The Council rations assessment so that it takes much longer to start, after the first contact is made, and naturally a lot longer to finish – with a final plan. Nothing is supplied or funded in the meantime. The law says that there must be an interim response after eligibility has been established. • The Council ignores eligibility altogether, and simply expects support planning to work out within the allocated resource based on a self- or supported- assessment questionnaire, against a foggy background of desired outcomes and a budget driven cost ceiling. The law says that eligibility assessment is a council function, and that assessment must be needs-led. More popular pitfalls.... • The questionnaire does not enable people to see how their asserted needs are being scored. The law says that people must be given a fair chance to understand what it is that they have got to satisfy the authority about…and how it will be measured. See Savva, and Cambridgeshire cases... • The questionnaire leaves out areas or domains which are clearly associated with community care services described explicitly in the legislation, like transport to services, or facilitating recreation. The law says that assessment must be offered across all potential community care services listed in the legislation. • The Council ignores local authority/public law about what sort of a person has to make which sort of decisions, regarding the care package and funding – giving the job to a local charity or reablement organisation, for instance. The law says that the function of assessment – the actual decision making about eligibility, funding or services and the deployment route (managed budget or direct payment) is for the council or its lawful delegates (that means the health service). Not a contractor. © Belinda Schwehr, 2011 5 More of same….more systemic pitfalls • The Council raises expectations too high, and then seems to be working according to wholly different rules about what sort of services it ever “provides” to anyone – and thus will fund, such as announcing ‘we don’t do night-sitting’ or ‘we don’t do cleaning’… ‘and therefore you can’t have any money for it….’ – this is an unlawful fetter on its discretion. • The Council’s resource allocation scheme applies an automatic discount for the mere fact that the client lives with another person. Or fails to inform people that it’s not a take it or leave it amount. Or is based on figures that have been plucked out of the commissioning units fantasy about managing the market, rather than real, local current costs... All challengeable by way of legal proceedings. • The Council’s Resource Allocation is described as ‘indicative’ but people are merely told to complain, if they are not happy with the amount. The law now says that they must be given written reasons for any refusal of money or items or services – by the actual decision maker – before they have finished their jobs. © Belinda Schwehr, 2011 6 How does the law support the buying of universal and preventive services? • Councils have always had very wide powers to make a difference locally, by means of interesting partnerships with Health, the voluntary sector, and other councils. These projects are for joint strategic needs and involve agency contributions, rather than solely the money of any one organisation. • Even without doing any assessments, Councils have got wide powers to buy or otherwise procure (ie through grants) the existence of both generally desirable and specifically community care type services for the area, in chunks, so that they’re just there for people to go and get for themselves, at a subsidised price, direct from the provider – or through charged-for social care services. These don’t have to be in a care plan, to be charged for. • Re-ablement and Intermediate Care are perfect examples – chargeable after the first 6 weeks. • Nobody gets a direct payment, however, unless they’ve been assessed as eligible. So nobody gets a personal budget for universal services.... © Belinda Schwehr, 2011 7 How the law has developed an individual adult’s social care rights – since 1997…. • Anyone with an apparent disability or long term condition is entitled to assessment of needs for services of a community care type. • These services are defined in s46 of the NHSCCA 1990 and cover 5 bits of current legislation, all worded subtly differently – and quite ambiguously. • Councils are entitled and obliged to consider whose needs are ‘eligible’, by reference to current Fair Access to Care Services guidance, based on the amount of ‘risk to independence’ arising from the needs, if no social care input were to be forthcoming, after everything else that might feasibly meet the need has been considered. • The threshold is local because social care is a local council function; and it can be raised due to financial shortage. But the approach to individuals’ presenting needs is fixed nationally. The 2003 FACS guidance said that the indicators of risk could only be added to, not changed so as to make them more restrictive. © Belinda Schwehr, 2011 8 An ‘assessment’ covers three main things, if it is to be legal: • • • • An assessment is not ‘done’ (in the sense of done properly and finished, discharging the council’s full duty) until someone’s needs (for community care services) have been a) identified and classified, as to whether the needs are even for social care; b) put through eligibility criteria, resulting in a decision as to which needs are so needy as to be eligible, and then c) care planned for, so that any eligible unmet needs are met appropriately (ie reduced down to the local FACS threshold) …in each case, all this has to be done by the local authority or a lawfully authorised delegate (eg under Partnership arrangements with Health). Finalised assessment decisions cannot (yet) be fully delegated through contract to outsiders, such as re-ablement providers or independent social workers. It’s coming though – via independent social work pilots.... In the next 3 years probably. The concept of meeting need ‘appropriately’ is a woolly one, but it does boil down to three things, from the case-law: – not unreasonably, in terms of professional consensus and social work values, – lawfully, in light of the rest of the UK’s general laws, like the Choice Directions and discrimination laws, and – compliantly with UK human rights, properly understood (eg art 3, arts 5,8, 9) © Belinda Schwehr, 2011 9 Are the council’s inevitable resources difficulties relevant to what’s appropriate in the first place? • A lack of resources (money in the social services coffers) is legally irrelevant to the duty to meet need appropriately in this sense: it’s not an excuse for not meeting need. It is a corporate (an LA’s, not just social services) absolute duty. • A council can use its financial position as one consideration in a range of considerations when determining what to offer a person to meet their needs. A cheaper setting can be offered, a cheaper service can be offered, so long as they are all adequate and appropriate. • A complete lack of resources - in terms of non-existence of any appropriate service to buy - is not something that the law can change, but the law says that something must be done or arranged in the interim, ie the next best thing, even if it costs more than was expected for the level of need concerned, in the short term. • If the authority agrees that the need can only be met in one way, appropriately, then the cost of any other inappropriate way is completely irrelevant – because it would not be lawful in the first place to use that other method. • Local authorities cannot therefore assume that everyone ‘can’ have their needs met for the cost of a residential care place, because for some at least, albeit only the exceptional few, it would never be appropriate, in terms of professional judgment. © Belinda Schwehr, 2011 10 More on the relevance of resources • However, the local FACS threshold can be put UP, because of economic hardship – so long as there is proper consultation beforehand. Two authorities are being sued at the moment for drawing a line through one of their bands, and I don’t think that that is lawful. • And, the person’s needs may be re-worded in a more general way, on a re-assessment, allowing for more room for manoeuvre, in relation to what would feasibly be seen to meet that newly described need. See McDonald • And also, in times of economic hardship, judges will be sympathetic to the contention that less than perfect ways of doing things, are at least not inappropriate, such that it will probably be seen to be lawful to offer the not so perfect means of meeting need, even though no-one thinks it’s that wonderful. That is the harsh truth deriving from the fact that all this money is public money – tax payers’ money, ultimately. © Belinda Schwehr, 2011 11 Community care legislation – in England – containing specific wording about services • S117 Mental Health Act – pretty well anything for someone discharged from compulsory section for their mental health aftercare needs • S2 Chronically Sick and Disabled Persons Act – home based services for disabled and ill people – home owners, tenants and licensees. • S29 and s21-26 National Assistance Act – general welfare services for disabled people, including the mentally ill, and care together with accommodation for eligible people without care and attention otherwise available to them • Sched 20 NHS Act 2006 – health related aftercare and preventative services, from social services, not the NHS. • For these last two, above, see here for the directions which make some such services into duties: http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Lettersandcirculars/LocalAuthorityCirculars/AllLocalAuthority/DH_4004121 • S45 Health Services and Public Health Act (pretty well anything for promoting the welfare of old people) So, what CAN the money be spent on? The wording of these Acts, means that - always assuming an assessed eligible need, and a proper resource allocation for the agreed deployment route – councils and clients can buy the following things: • Anything in the way of care and attention or support or supervision • Any items that would add to the person’s comfort safety or convenience • The cost of membership or entry to activities that count as recreational facilities • Items or activities that enable the keeping up of contact with the world and society • Transport to services or events above and beyond other concessionary transport that is offered, if it is appropriate for use by the individual. • Anything that the legislation comprising the full range of community care services could possibly be stretched to cover – that’s fully 5 Acts of Parliament at this point A “wireless, TV or similar recreational facility” is the language used in the CSDPA statute, for instance – and it is clearly able to be stretched to cover a computer, if that is cost-effective enough to convince the council that it’s appropriate to fund. What is the test for what the budget can NOT be spent on? • But not things that are clearly outside the language: for instance – using the Budget to pay off a tribunal claim brought by a Personal Assistant for personal wrongdoing of the employer. – services which are clearly specialist enough to strike anyone as nursing services – NHS money is for that, not social services’ money. – speculating on the hedgefund market! • Not something that it would be unlawful for anyone to buy – eg class A drugs. • Not – if the client has taken a direct payment, on in-house services – the consensus seems to be that if a person wants a council-provided service, s/he must leave the cost of that service in the managed part of the budget, and cannot spend a direct payment on buying services direct from the council. That could be different if one’s provider were a local authority trading company. • Not anything that the council chose to forbid in advance, or at sign-off, because it feared reputational damage when dealing with the flak from the media, even if it wasn’t illegal and wasn’t outside the community care services legislation…. • Not anything that the council refused to approve in the support plan, on grounds of disproportionate risk management issues, or the impact on others in the community. Where do ‘Fair Access’ Criteria fit? • The guidance says that one central thing is being assessed – the amount of risk to independence if no social services are put in – after all one’s friends’/ neighbours’/ relatives’ willing and able assistance, and access to other things, (health, housing, etc) have been deducted. .. • It is not the person, nor the extent of the person’s disability/illness, itself, being assessed – it’s unmet eligible assessed need – in particular domains relevant to social care. • So the system already allows for people to help themselves, or be helped by their families etc. – but it impacts on their entitlement. • Withdrawal of crucial informal support logically increases need, and hence eligibility. But what is a want, as opposed to a need? It’s the council which gets to decide, subject only to judicial review. • Why? Because it’s public money paying for it! © Belinda Schwehr, 2011 15 Legal status of the 2010 guidance • The new guidance is virtually mandatory for councils – here is the link: http://www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/@dh/@en/@ps/do cuments/digitalasset/dh_113155.pdf • It is issued under the auspices of s7 Local Authorities Social Services Act 1970 which compels Councils to act under the general guidance of the Secretary of State: “7 (1) Local authorities shall, in the exercise of their social services functions, including the exercise of any discretion conferred by any relevant enactment, act under the general guidance of the Secretary of State.” • Virtually mandatory, that is, because no guidance is absolutely binding; it would not be guidance, if it was - it would be LAW. • But this means that if a council’s decision makers (whoever they may be…) – Don’t know about it – Don’t appear to follow it, or – Don’t explain why they are not going to follow it in a given case …the council would be open to judicial review… and if it were to lose, the funding decision would be void, and would have to be taken again, properly, second time around. Critical needs/risks to independence – if no social services are provided Critical – it’s when – if nothing is done about it • life is, or will be, threatened; and/or • significant health problems have developed or will develop; and/or • there is, or will be, little or no choice and control over vital aspects of the immediate environment; and/or • serious abuse or neglect has occurred or will occur; and/or • there is, or will be, an inability to carry out vital personal care or domestic routines; and/or • vital involvement in work, education or learning cannot or will not be sustained; and/or • vital social support systems and relationships cannot or will not be sustained; and/or • vital family and other social roles and responsibilities cannot or will not be undertaken. © Belinda Schwehr, 2011 So what does the actual guidance do? • The guidance re-states what may seem like an obvious truth – the bands do not represent particular types of need, or risk, in a hierarchy of seriousness - but instead, refer to the size of the risk to a person’s independence, in particular domains of living, being caused by the totality of their particular difficulties. • So not being able to undertake any, or only one or two normal domestic routines could be deemed to be a critical risk, if a vital routine was involved, even if what is required to solve this was a cleaning service, and not personal care. Likewise with social inclusion risks, inability to access services, etc. • It is a complete myth that cheap services or small packages are the outcomes of low or moderate needs. There is no logical correlation between the cost of a package for someone from the LD client group who scores x across the domains of a, b, c, d and e, and the cost of a package for someone who scores the same over different domains. The descriptors are not in a hierarchy and the domains generate different needs for different types of service, not all of which are charged by the hour. • NO system of RA is determinative, because it is used before support planning and negotiations with families. FACS is even helpful on clarifying the relevance of the client’s own funds Para 77. From the beginning of the process, councils should make individuals aware that their individual financial circumstances will determine whether or not they have to pay towards the cost of the support provided to them. However, an individual's financial circumstances should have no bearing on the decision to carry out a community care assessment providing the qualifying requirements of section 47(1) of the NHS and Community Care Act 1990 are met. Neither should the individual’s finances affect the level or detail of the assessment process. Relevance of the client’s own money to eligibility: Para 71. This means that once a person has been identified as having an eligible need, councils should take steps to ensure that those needs are met, regardless of the person’s ability to contribute to the cost of these services. An assessment of the person’s ability to pay for services should therefore only take place after they have been assessed as having eligible needs. A person's ability to pay should only be used as a reason for not providing services in circumstances where a person has been assessed as needing residential accommodation, the person has the means to pay for it and if the person, or someone close to them, is capable of making the arrangements themselves. © Belinda Schwehr, 2011 20 The risk of ignoring the ordinary residence guidance • Buckinghamshire decided to sue another council for dumping a person into independent living in Bucks’ area. • It’s interesting that nobody sued Bucks for absolutely refusing to assess a person who was already living there with a disability! • The ordinary residence guidance makes it clear that a person with capacity moves their place of ordinary residence when they take up a tenancy in another area, and are entitled to assessment from the new authority. Not necessarily services of course, because the threshold might be different. But that means that the exporting council’s care managers jolly well need to liaise before ‘facilitating’ these moves, in the name of Valuing People (!) • Bucks lost the case on the issue of mental capacity, because Kingston’s care planners had genuinely followed the Mental Capacity Act duty to maximise the person’s understanding of what she was being invited to sign! • The case sets out a usefully very low test for mental capacity to sign a tenancy – but there is still a test! © Belinda Schwehr, 2011 21 • The Law on the implications of the two deployment routes that can be used for personal budgets... • And on some particular aspects of direct payments – the ‘preferred form’ for a personal budget – by 2013. © Belinda Schwehr, 2011 22 Deployment routes… • There are essentially two ways to take a personal budget – as a direct payment or as a ‘managed’ personal budget. • ‘Managed’ – in this context - means the council’s officers concluding the contract for the service, in as personalised a way as providers will allow, or feel it would be necessary or feasible to offer. NB - If the client agrees to have a direct payment, and gives it to someone to manage, the client will obviously think of that as a “managed” personal budget as well, so you do need to be careful here with language. The council managed PB route is always subject to public procurement rules and standing orders. If the council changes providers, TUPE will or at least MAY apply. • • • • • Direct payment clients’ purchases are not subject to public procurement. They are individual private purchases, even though the money came from local government. With a Direct Payments PB, the client is the purchaser, the employer, the contractor – and thus owes the legal obligations associated with all those roles – and is bound by any legal rules governing direct payments. It could be the council that the Direct Payment client would like to manage the payroll or the payment system for purchases. What is then done by any such council is NOT public procurement – that’s the council choosing to act as the client’s agent – under s2 of the Local Government Act 2000. Who is the purchaser? • In a direct payment the client decides who to contract with and how to carve up their own budget, subject only to the constraints of the direct payment agreement they will have signed with the council. • In a managed personal budget, the council is the contractually liable party in terms of payment. The contract is ‘for’ the client in one sense, but does not lumber the client with any formal contractual obligations. • When contracting, the council is bound by its own standing orders, procurement law, and the state aid rules. • It does not have to offer choice of provider to the client, in legal terms, but the performance targets from central government require and most councils accept that if they are to use these routes to delivering services, that the client is happy that they have been able to control the manner and timing of the services. • Note that NI130 does not say the identity of the provider, for managed personal budgets! © Belinda Schwehr, 2011 24 What does the personal responsibility of the client mean under a direct payment? • Well, it means that the provider can’t go to the council for payment, if the client doesn’t pay, for instance. • The provider cannot be told by the council what quality of service to provide, or how much to charge. • The provider doesn’t have to be an approved provider of the council. Or even regulated, if it’s an individual buying the service for themselves or a family member, from another individual. • The council can tell providers how much it proposes to offer to clients to fund various types of care, but that is not binding on the provider, who may well say that that rate is no use at all to them. Market forces will ultimately determine who is right. • The client is liable for employment law wrongs, not the council (unless the council has behaved wrongly at an earlier stage....) • The client owns the equipment bought with a DP and must be responsible for taking care of it... © Belinda Schwehr, 2011 25 The law on the displaced functions and obligations of the responsible authority – the duty to care gets suspended when a DP is taken... 14.—(1) Except as provided by paragraph (2), the fact that a responsible authority makes a direct payment shall not affect their functions with respect to the provision under the relevant enactment of the service to which the payment relates. (2) Where a responsible authority make a direct payment, they shall not be under any obligation with respect to the provision under the relevant enactment of the service to which the payment relates as long as they are satisfied that the need which calls for the provision of the service will be secured by— (a) in the case of direct payments under section 57(1) of the 2001 Act or section 17A(1) of the 1989 Act, the payee’s own arrangements; or (b) in the case of direct payments under section 57(1A) of the 2001 Act, the arrangements made by S (the Suitable Person). © Belinda Schwehr, 2011 26 Would it be wrong to spend a direct payment on something outside the support plan? The fact that A) the amount of a direct payment has to be worked out by reference to the likely cost of the services in the care plan, (not just the ‘outcomes’ or ‘objectives’) and B) there are recovery provisions for misuse; and that C) not spending the money on the services in the support plan is also a ground for recovery … suggests to me that ordinary Direct Payments ARE implicitly so linked to the community care services that would otherwise have to be provided by a council. Even the Audit Commission’s web-page said about DPs: “The money can only be spent on a narrow selection of traditional social care services (specified in the care plan). The focus is inputs, rather than outcomes.” © Belinda Schwehr, 2011 27 The law on repayment of direct payments 15.—(1) A responsible authority which have made a direct payment may require the payment or part of the payment to be repaid where they are satisfied that— (a) the direct payment or part of the payment has not been used to secure the provision of the service to which it relates; or (b) a condition imposed under regulation 11 or 12 has not been complied with. (2) Any sum falling to be repaid by virtue of paragraph (1) shall be recoverable as a debt due to the responsible authority. © Belinda Schwehr, 2011 28 The law that permits Direct Payments to be spent on spouses, or close relatives in the same household if the council agrees it’s really the only way forwards 11.—(1) A direct payment under section 57(1) of the 2001 Act or section 17A(1) of the 1989 Act shall be subject to the condition that the service in respect of which it is made shall not be secured from a person mentioned in paragraph (2) unless the responsible authority are satisfied that securing the service from such a person is necessary — (a) in the case of a relevant service as defined in paragraph (a)(i) or (ii) of the definition of that term in regulation 1(2), to meet satisfactorily the prescribed person’s need for that service…. © Belinda Schwehr, 2011 29 Direct payments and Pre-Paid cards • • • • • The essence of a direct payment is a payment. Ordinary people would think of a payment as receiving a sum of money and it passing to the recipient. If you’re not giving people the money, but keeping the money in a council bank account and just giving out cards, I don’t think you can call it a direct payment. Virtual control over it would have to be argued to amount to the same as owning it, legally, and whilst I can see that you could have a good go, I don’t think the courts would go for it. If it’s not a direct payment, then the client isn’t the real purchaser of the service. The council would be the real purchaser. That raises public procurement and standing order issues, and even employment of PA issues, but they are not insoluble. The only other way councils could be doing this through something called a direct payment is if they got people’s acceptance of a direct payment and then could document asking them whether they’d like the council to manage it for them. On that footing it might be argued that the fact that the money is in a corporate account is not an issue that defeats it being a direct payment: the council is acting only as agent for the DP holder, with the person’s capacitated consent. That way councils would only be purchasing services or providing a payment service as agent for each client as an individual principal and would not be contractually liable.. © Belinda Schwehr, 2011 30 Can the client buy council-run services with their direct payment? • The legal consensus seems to be ‘no’, because local authorities are creatures of statute and can only do what they have power to do under statute – they don’t have a power to sell services directly to the public... • They can provide social services, of course, in return for a charge, but that’s a statutory charge, and the supply is not under a contract, and that’s why it doesn’t need the consent of a client – useful if the client lacks capacity. • The client can simply leave the part of their budget that they want to spend on in-house services, with the council in a managed personal budget, in the council’s account, to offset the cost of the in-house services, instead of taking it as a direct payment, so it doesn’t really matter. • But some councils are preparing to hive-off trading arms, called LATCs, so that council in-house staff can be used as secondees, or TUPE over to that organisation, to provide commercially-priced services to direct payments clients who choose to buy them, and to fully private self-funders…. Can councils pay for voids on top of managed personal budgets or direct payment clients’ own deals? • Yes, in my view – they can do it under their general social care powers, or for the well-being of the community or because they have to, in order to develop the market. • Councils have statutory power to make arrangements for social care services, whether or not there are clients who are formally eligible for them. • Their community care powers enable them to procure blocks of service for whoever is then sent in that direction. Also they can give grants to ensure that certain things happen in the community. • Providers who have clients with care packages and direct payments, or council contracts for within-resource allocation amounts, may well need voids commitment contracts on top to enable them to function viably. © Belinda Schwehr, 2011 32 • Helpful law and regulations connected with direct payments for incapacitated people... © Belinda Schwehr, 2009 33 The new direct payment framework for incapacitated people who can’t consent • • • • • • • On November 9th, 2009, new regulations came into force which govern the giving of direct payments to people who lack capacity to consent to one in person. The person who consents, lets the council off the provision hook, and then takes and spends the money is dubbed the service user’s ‘Suitable Person’. Most such people who might step forward to take on this responsibility will not be lawfully authorised to act in any OTHER way, so as to make them the formal agent of the service user. They will not usually be an attorney or a deputy, so they won’t have access to the person’s own money, unless they have a joint bank account already, with that person. And they will not be able to be deemed to have been ‘appointed’ the person’s agent, by the person him or herself, because the person will, by definition, have nil or barely any capacity, with which to make that choice. So – the Suitable Person, AND NOT THE CLIENT - WILL BECOME THE REAL EMPLOYER OF WHOEVER IS THEN GIVEN THE Personal Assistant role, or the PURCHASER of the services rendered or the goods supplied. So taking on this role carries criminal and other civil legal responsibilities which you would naturally want to know about, before saying yes! © Belinda Schwehr, 2011 34 What can a Suitable Person DO with a person’s direct payment, legally? • They don’t have any lawful authority to act ‘for’ the client as agent in relation to the Direct Payment that counts as the client’s money once it’s been passed over. • They can’t make a formal contract with the money, at least not in the name of the client. • They are the recipient of the money and have lawful access to it, because they have been chosen by the local authority who would otherwise have had to provide or purchase. • They have lawful access to the money, but it’s an interesting question whether it’s the client’s money – in legal terms. Who has legal ownership of the money? I think it’s the Suitable Person. • One of the conditions is that they act in the Best Interests of the client, but there is no Ct of Protection regulation of them. • They can make contracts in their own name with the DP money for the purposes set out in the support plan. • It doesn’t make them an appointee, for management of benefits, automatically. My view is that they should be acknowledging the conditions, directly, in their own name with the local authority, so that they are acknowledging the conditional nature of the appointment thereby making it feasible to prove misuse or abuse of that position. © Belinda Schwehr, 2011 35 From the perspective of the provider The Suitable Person scheme … • Enables the provider to contract directly with a person who is fully capacitated for communication and liability purposes • Enables the council or the provider to review support plans with a fully capacitated person, annually. • Enables the council to put even more people onto direct payments, and then control the money supply that governs what providers may think it’s feasible to charge, subject only to judicial review for unreasonableness etc © Belinda Schwehr, 2011 36 From the perspective of the Suitable Person… • The scheme enables them to organise care without having to be CRB’d or risk being barred, and without checking for the status of the staff they choose to take on, if the SP is an individual unpaid friend or family member of the service user, making private arrangements with workers. • If they are unpaid friends or family of the service user, SP status means that they do not have to register with the CQC as providers (arrangers) of personal care. • They are not exposed to risk of being barred, despite doing regulated activities under the SVGA, if they are family or unpaid friends, doing the arranging. • Whether this is good or not, of course, for the client, is a moot point. © Belinda Schwehr, 2011 37 From the perspective of the council Appointing a suitable person … • Involves having a policy, staff and paperwork to do your legal duties; most still don’t... • Gets direct payment numbers up – if there are any incapacitated people still around who haven’t already been given an unlawful one • Ensures accountability for the public money, in the hands of someone who can be pursued, properly, for breach of conditions and misuse • Protects the client from risk of liability that could never be easily enforced • Saves on care planning time, because it passes over the job to the Suitable Person, who must work in an MCA-compliant way. © Belinda Schwehr, 2011 38 • Resource allocation law and guidance • Due process, fairness, transparency and reasons – from the beginning of the system, right through to the end! © Belinda Schwehr, 2009 39 The resource allocation system – DH guidance 129. The aim of the RAS should be to provide a transparent system for the allocation of resources, linking money to outcomes while taking account of the different levels of support people need to achieve their goals. It allows people to know how much money they have available to spend so that they can make choices and direct the way their support is provided. 130. Calculating what resources should be made available to individuals should not detract from a council’s duty to determine eligibility following assessment and to meet eligible needs. Rather a RAS should be applied as a means of giving an approximate indication of what it may reasonably cost to meet a person’s particular needs according to their individual circumstances. It is important for councils to ensure that their resource allocation process is sufficiently flexible to allow for someone’s individual circumstances to be taken into account when determining the amount of resources he or she is allocated in a personal budget. Running out of money – the English FACS guidance says ‘Tough’! 124. Councils should plan with regards to outcomes, rather than specific services. They should consider the cost-effectiveness of support options on the merits of each case and may take their resources into account when deciding how best to achieve someone’s agreed outcomes. However, this does not mean that councils can take decisions on the basis of resources alone. Once a council has decided it is necessary to meet the eligible needs of an individual, it is under a duty to provide sufficient support to meet those needs. Councils should provide support promptly once they have agreed to do so, but where waiting is unavoidable, they should ensure that alternative support is in place to meet eligible needs. Procedural fairness – the newly explicit requirements in the government guidance! Para 106 of the FACS guidance from 2010: Where councils do not offer direct help following assessment, or where they feel able to withdraw the provision of support following review, they should put the reasons for such decisions in writing, and make a written record available to the individual. Councils should tell individuals who are found ineligible for help that they should come back if their circumstances change, at which point their needs may be re-assessed. A contact number in the council should be given. The first reported case on the rationality and transparency of RA systems – Mrs Savva • Mrs Savva was a 70 year old client, who suffered from diabetes, heart and respiratory problems, and was arthritic with poor eyesight. She had had a stroke some 10 years ago, and she had been in receipt of care services from the Local Authority since that time. • The challenge related to the decision first made in late 2009, to provide the Claimant with a personal budget of £170.45p per week. • It had started off at £82.91 when she was first put through the RAS in the summer. She HAD got 16 points on the RAS at first. • Later the points score was adjusted to 28 points and the funding was adjusted to £132.56p, and this was then finally increased to £140 odd and then to £170.45p - without any more points being ‘granted’. © Belinda Schwehr, 2011 43 The arguments in Savva The council said as follows, at court, in defence of its use of a RAS: “The RAS tool is a mathematical tool which has been promoted by the DH and adapted for use by the Council. The rationale behind the tool is to ensure objective consistent needs-based decision making in the context of community care. The RAS tool is designed to help the Panel in its analysis. It generates an indicative budget only.” The “indicative budget” generated by the Council’s November 2009 RAS, when translated from a points score of 28 points to a monetary value, amounted to £112.21p. This sum, of course, was an increase from the £82.91p generated subsequent to the July SAQ. This sum was then adjusted to £142.02p per week. “Analysing the claimant’s needs in the round, the panel considered that the ‘indicative budget’ of £142.02p per week was too low and did not properly meet the Claimant’s needs particularly in terms of meal preparation. Therefore, the panel increased the indicative figure and allocated a weekly budget of £170.45 to the Claimant.” © Belinda Schwehr, 2011 44 On the need for reasons…. The Directors of Adult Social Services in their document “Common Resource Allocation Framework” dated October 2009 state that ‘up-front allocation’ means that the person is told, before a support plan is agreed, roughly how much money is likely to be required to fund such support. The same document emphasises ‘Transparency.’ It says that the RAS should be transparent, which means being clear how decisions are made and making the system public. This guidance from the senior social workers in this field provides support for the view that policy in this area favours a transparent approach which provides service users with clarity on how decisions are made prior to a support and care plan being agreed. Thus, although there is no statutory duty to give the reasons why a Panel arrives at a particular monetary personal budget, all of the documents produced by the Government Departments and by the Association of Directors of Social Services point to transparency, openness, and consultation, prior to the drawing up of an agreed Care and Support plan. © Belinda Schwehr, 2011 45 Reasons for funding sign off and for DP sums “The personal budget must be sufficient to purchase the services and is needs-led, and it seems to me that the only way in which a service user can be satisfied that the personal budget has been correctly assessed by the Panel is by a reasoned decision letter. ...Without being able to properly understand the use made of the RAS, the service user and anyone acting on her behalf, is left totally in the dark as to whether the monetary value of £170.45 is adequate to meet the assessed need of a 28 point score. • The process of conversion made by the Panel is not explained to the service user. It should have been underpinned by an evidential base, and it was not.” • The stage of production of the support plan and the care plan, in my view, is too late for the Claimant to be provided with reasons for the budget. • That cannot represent an adequate discharge of the obligation on a local authority to explain the reasons for its decision in this area in a transparent manner.” © Belinda Schwehr, 2011 46 Both sides appealed :• The Court of Appeal dismissed both the appeal challenge to the legitimacy of using a RAS at all and the appeal challenge to the need to give reasons • The Court refused to decide whether it would be enough to discharge the duty of fairness to hand the money over just saying ‘You can always ask us for reasons if you want them’…! • The council has done a wonderful thing for disabled clients by appealing, because it has set a precedent, now, which must be followed! © Belinda Schwehr, 2011 47 The judgment in Savva suggests that councils need to be able to offer two things if it wants a RAS at all: a) a rational articulation of why the Resource Allocation system deserves to be seen as a sensible guesstimate of the cost of meeting particular levels of needs in particular domains. Ie a basic explanation, in leaflet or website format, of the council’s decision to rely on a ‘comparable current cost’ approach, or some other approach and why the figures lay claim to being based on a rational evidence basis. However, neither of these explanations of policy, would suffice in themselves, without something focusing on the individual service user’s situation, at the final sign-off of a Plan, the size of the budget or the size of a direct payment. So the second thing needed would be b) a reasoned decision as to why the final allocation is then thought to be adequate, to achieve the meeting of the assessed needs in the manner agreed in the Support Plan. The decision would have to address the service user’s reasons and evidence for saying that it would not reasonably be seen to be sufficient, with the council’s reasons for deciding that it would in fact suffice, or have to suffice, despite not fully enabling the service user’s preferred outcomes, in terms of the manner of, or setting for, the meeting of the need. © Belinda Schwehr, 2011 48 Two important paragraphs from the FACS guidance on the contents of and approach to the support plan 121. Councils should agree a written record of the support plan with the individual which should include the following: • • • • • • • • A note of the eligible needs identified during assessment; Agreed outcomes and how support will be organised to meet those outcomes; A risk assessment including any actions to be taken to manage identified risks; Contingency plans to manage emergency changes; Any financial contributions the individual is assessed to pay; Support which carers and others are willing and able to provide (voluntarily); Support to be provided to address needs identified through the carer’s assessment, where appropriate; and A review date. 124. Councils should plan with regards to outcomes, rather than specific services. They should consider the cost-effectiveness of support options on the merits of each case and may take their resources into account when deciding how best to achieve someone’s agreed outcomes. However, this does not mean that councils can take decisions on the basis of resources alone. Once a council has decided it is necessary to meet the eligible needs of an individual, it is under a duty to provide sufficient support to meet those needs. Councils should provide support promptly once they have agreed to do so, but where waiting is unavoidable, they should ensure that alternative support is in place to meet eligible needs. © Belinda Schwehr, 2011 49 Cambridgeshire 2011 – a bit of a retreat on reasons, where direct payments are concerned – but still consistent with legal principle • Cambridgeshire’s RA Scheme (based on direct payment costs, not commissioned costs) had a ‘higher costs’ table for higher cost care packages. • The triggers were night time care, 2:1 care, specialist care and specialist AND 2:1 care. • They worked out a man’s package, using an independent social worker, who recommended £120K a year. The council accepted the assessment of need, but not the extent of the services he’d recommended to meet need, and offered £75K instead, using the higher cost table, and the expertise of a senior manager, in order to figure out how much was needed. The remainder, after personal care and support had been accounted for, was an apparently unexplained sum drawn from the council’s mainstream RAS. • The decision was upheld, with the court saying that there was no need in a direct payment personal budget to explain exactly how the money would even theoretically be enough. That was the whole point of direct payments – choice and control for the client. • However, the judge stressed that the approach taken to the vast bulk of the funding and its adequacy was clearly not irrational, even if it was not spelt out exactly. He didn’t say anything about the need for reasoning about the remaining chunk of the money for leisure and recreation. The Court of Appeal’s approach • The man’s appeal failed because • (a) the local authority, whose funds were not limitless, was both entitled and obliged to moderate the assessed needs to take account of the relative severity of all those with community care needs in its area, • (b) the local authority was not obliged to meet an individual’s needs in absolute terms; • (c) the use of the RAS (THIS RAS, Belinda thinks, not all RASs!) as a starting point was lawful and the local authority’s decision did not have to extend in every case to explaining the RAS in detail • (d) The explanation given by the local authority to K as to how the sum of £84,678 was arrived at was rational. It properly showed how that sum had been reached, and sufficiently demonstrated that that sum would meet K’s assessed needs • Link for the case: http://www.bailii.org/cgibin/markup.cgi?doc=/ew/cases/EWCA/Civ/2011/682.html&query=title+(+ cambridgeshire+)+and+"resource+allocation"&method=boolean © Belinda Schwehr, 2011 51 The Cambridgeshire case - analysis • • • • When finalising the amount of a direct payment, social care decision-making panels/staff are only obliged to convey a rational justification for believing that the funds awarded are broadly equivalent to the reasonable cost of securing the provision of the service concerned. The ‘arrangement’ for meeting need that must be put into the support plan might well be a Direct Payment – if that’s what’s been agreed, in which case the client can choose, ultimately, how to spend it, so that the amount allocated need only be broadly justified, not explicitly calculated by reference to identified services. When finalising the resource allocation for a direct payment form of personal budget, the council must still have a rational view based on competent staff’s opinion, of how much of a generic type of service would actually be required to meet need, in order to be able to explain why the amount finally allocated deserves to be seen as not arbitrary, and as reasonable. A resource allocation calculation cannot ‘drive’ the assessment of need, which must still be needs driven, and not budget driven – and that the final amount must focus on the individual, even if final costing is done by reference to the average cost of meeting the needs of the client group of which he or she is a member. © Belinda Schwehr, 2011 52 “We think that £x will be enough…” • • • • • • • • Faced with the council’s position that the client ‘should’ be able to make do with £x, the client or their advocates should ask – because they are entitled to know the basis for the council’s opinion – Why, please? Who from, please? Why do you think that that’s an adequate appropriate service for me as an individual, given that….[fill in the blanks] Why do you think that the unit cost of So and So’s services would enable you (or I) to buy sufficient services for my particular needs at the price you’ve offered to fund me for, given my needs are specialist or high cost because of [fill in the blanks]? Even so, shall we ask them if they’ve even got a vacancy or capacity to take ME on? Or say: I don’t think that I fancy a direct payment at all, thanks. I’d rather you lot commissioned an appropriate service for me and invoice me for my contribution, but I’d like it personalised as to the timing and manner of its provision, like the government guidance says it should be…. © Belinda Schwehr, 2011 53 • Support planning legal developments • Reviews, re-assessments and rewording the needs.... © Belinda Schwehr, 2009 54 Careful Process on Reviews – from government guidance on FACS 109. Councils should exercise considerable caution and sensitivity when considering the withdrawal of support. In some individual cases, it may not be practicable or safe to withdraw support, even though needs may initially appear to fall outside eligibility criteria. Councils should also check any commitments they gave to service users or their carers at the outset about the longevity of support provided. If, following a review, councils do plan to withdraw support from an individual, they should be certain that needs will not worsen or increase in the short term and the individual become eligible for help again as independence and/or wellbeing are undermined. [This is warning about evaluating the real risks that will arise from removing services, and the possibility of a claim based on legitimate expectation based on past assurances. It gives councils a legitimate footing on which to put extra criteria in the bottom of their lowest category along the following lines: “This extent of risk is not really in this eligible category, but it would be within a very short time, in the absence of services – so it would be daft to ignore it”.] Reasons on conclusion of reviews – DH guidance 143. Councils should record the results of reviews with reference to these objectives. For those service users who remain eligible councils should update the support plan. For those people who are no longer eligible, councils should record the reasons for ceasing to provide support and share these with the individual both verbally and in writing. They should also offer information about the forms of support that may be available to the individual in the community. But who really is the final decision-maker for support planning? It’s the councils... Elaine McDonald v Kensington & Chelsea London BC • Where a local authority was obliged to meet the assessed needs of a lady who had a neurogenic bladder as a result of a stoke, they were entitled to meet the need in the most economic manner – they could lawfully leave her to provide incontinence pads rather than fund a night time carer to take her to the toilet. • The National Health Service and Community Care Act 1990 gave the Local Authority some flexibility as to how the needs could be met. • On appeal – there had been no Disability Discrimination or breach of human rights, or breach of public law, after her needs were re-formulated more generally than before, as the authority had conscientiously sought to treat her the same as everyone else – lawfully. © Belinda Schwehr, 2011 57 The background to the McDonald incontinence pads case • • • • • • She had been given funding for night time assistance as what was described as ‘a concession’, pending an application to the Independent Living Fund, as a short term measure only. That ILF application does not appear to have been accepted. The council had been proposing for some years that she should be willing to use incontinence pads or special Kylie sheeting to urinate into which would avoid the need for a night-time carer. The council said that this would provide the appellant with greater safety (avoiding the risk of injury whilst she is assisted to the commode), independence and privacy, besides reducing the cost of her care by some £22,000 per annum. Ms McD was appalled at the thought of being treated as incontinent (which she is not) and having to use pads. She considered this an intolerable affront to her dignity. Lords Dyson Brown and Walker agreed it was not an unlawful approach, on the part of the council, nor a breach of her human rights, nor a breach of the DDA legislation. Lord Kerr agreed but for different reasons. She was so contemptuous of the others’ reasoning that they got upset and were pretty rude about her too! © Belinda Schwehr, 2011 58 McDonald - the Supreme Court’s decision – July 2011 Ms McDonald has lost her case in the highest court in the land. She may now go to Europe, but it is unlikely, in my view. It’s a judgment that makes it a lot harder for others to challenge the adequacy of the support plans that are ultimately signed off. 13. “… the council could hardly have gone further in compliance with the Secretary of State’s Directions in their efforts to consult the appellant and if possible agree with her the services they were considering providing to meet her needs. The 2010 Review rightly described the client’s position on this as “entrenched” and the situation reached, as at an “impasse”. © Belinda Schwehr, 2011 59 Why she lost:– irrationality is the test for Judicial Review, and there was the following evidence: • “Lady Hale's judgment, agreeing with Age UK's argument that RBKC have been "irrational in the classic Wednesbury sense", seems to me to ignore completely the evidence of Mr Thomas Brown, the very experienced Head of Assessment at RBKC's Adult Social Care Department: – "The court should be aware that the solution of incontinence pads in a case of this nature is not exclusive to RBKC, nor did the suggestion that the claimant should wear them originate from social services, as my previous statement makes clear [it came from her own GP]. In my experience the use of incontinence pads for patients who are not clinically incontinent is both widespread and accepted practice in the provision of social services. Whilst RBKC accepts that the claimant is not clinically incontinent of urine, it is important to emphasise that her difficulty is that, due to impaired mobility, she cannot safely transfer from bed to a commode at night. In practical terms this presents substantially the same problems as a person who is incontinent. “Miss McDonald strongly differs from this view, and so may others. But I do not see how it could possibly be regarded as irrational.” © Belinda Schwehr, 2011 60 The witness also said this, about ‘practice’: • • • • “I am aware of guidance (DOH 2000) to the effect that incontinence pads should not be offered 'prematurely' in order to prevent dependence on them. I am also aware that aids and adaptations should be explored before such an option is considered. Unfortunately the claimant's situation is such that there is no equipment or adaptation which will enable her to access the toilet or commode without assistance. In any event any movement, even assisted, carries a risk to the claimant's safety. The primary care need of the claimant is to ensure her safety by protecting her from the risk of further falls, and I remain of the view that the use of night-time pads and/or absorbent sheets maximises the claimant's safety. Having regard to the guidance and to the particular circumstances of the claimant as well as to the cost indications of the care options, I remain satisfied that the use of continence products is appropriate notwithstanding the claimant's objections. I note her concerns about privacy and dignity and about the need to maintain her relationship with her partner. It is the council's view that the use of continence products provides greater privacy and dignity than the presence of a carer assisting with personal and intimate functions at night-time." © Belinda Schwehr, 2011 61 The hypothetical faeces factor…it was maybe not so very hypothetical! • Mr Brown’s evidence continued thus: – "It is my experience based on 16 years in social care (most of them working with older people) and another four years working in a large general hospital that, in medical and residential care settings, it is general practice in the management of functional incontinence [such as in Ms McD’s case]to use night-time incontinence pads or absorbent sheets as a means of ensuring safety in patients/residents with severely compromised mobility. – This management technique was suggested to the council by the claimant's GP Dr Parameshwaran on 19 September 2006 and also by the district nursing service, and the suggestion is consistent with my own knowledge of the care management of such persons. – The management plan would remain the same if the claimant needs to pass faeces at night, although good practice would be to encourage toileting last thing at night when her night-time carer visits and to encourage appropriate dietary changes. – The need for morning bathing will arise whether or not faeces are passed at night and it is practical within the care package offered by the council. It should be noted that the need to pass faeces at night was not raised as an issue at the most recent review held in March 2010. © Belinda Schwehr, 2011 62 What to avoid when support planning • • • • • Support planning that broke some other law – “You can choose from these two homes in the area, as they are the cheapest available. That’s your Choice Rights”. – “You will be provided with this food, even though it is against your religious and cultural sensibilities; Support planning that ignored mental incapacity (ie “We will put you in this tenancy even though you can’t understand it, and don’t have a deputy, and it saves us money because it will be out of our area.”) Support planning that was only resources-led – ie in Bromley’s case some years ago they said no to a great but high-cost placement found by the client’s mother, before finding any other options with which to compare it. Taking a blanket approach to support planning for a particular group on reassessment: “We will bring everyone out of area back to their home county, regardless of their local roots and relationships established over many years.” Taking the view that the person’s friends and relatives must provide accommodation or care – regardless of whether they are willing or able, this is not the case for an over 18 year old – it may be an unmet need. © Belinda Schwehr, 2011 63 Conclusions • Proper re-assessments must be done before any cuts are proposed; • Resource allocation scheme guestimates are lawful as a starting point, but indicative only; • The more rational and the less arbitrary the underpinning to the RAS, the fewer cases will have to be moderated with reasons; • Sign-off of a plan is an essential part of the statutory function and of following guidance; • Saying no to a request for more than first offered must be done with reasons, or at least explained, so as to stake a claim to being rational, and not merely budget-led. © Belinda Schwehr, 2011 64 Thank you so much for attending! • Belinda can be contacted on belinda@careandhealthlaw.com, or Tel 01252 725 890 or 07974 399361. • My website, www.careandhealthlaw.com, offers free (and some charged-for) topic overviews about health and social care law; ‘hot news’ emails when an important case has been decided by the courts, and access to these web-based training courses. • For traditional face-to-face training, and regional events, contact Mary Humphrey, my reservations manager, on 01379 678 243 or by email on mary.humphrey@nationalhomecarecouncil.co.uk