Wealth, Poverty and Possessions in Luke's Gospel.

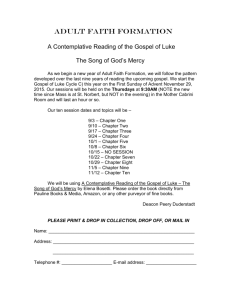

advertisement

Wealth, Poverty, and Possessions in Luke’s Gospel

Luke Lesson Series

Amanda Pittman

Seminar in the Gospels

Dr. Ken Cukrowski

December 10, 2009

Pittman 1

Wealth, Poverty and Possessions in Luke’s Gospel.

Series Introduction

Luke has a way of bringing wealth, poverty, and possessions into the

conversation, in some cases unexpectedly. At times he does this in material unique to

him, the parables of the rich fool in 12:1-21 and the rich man and Lazarus in Luke 16:1931, for example. In other places, he does so through insertions into material from Mark

or Q, as in the teachings of John the Baptist in 3:1-20 or those on loving enemies in 6:2736. In the case of Lukan additions, while they do not supplant the message of the

pericope in which they are found, they do add a Lukan nuance to these topics that should

not be missed. This lesson series aims to present Luke’s teachings on the rich, poor, and

the role of possessions in the life if each, with attention to the contexts in which they

appear. Within Luke, “poor” refers to more than an economic status, though it certainly

addresses that factor as well; the term describes a group of downtrodden people,

including people imprisoned, blind, hungry, weeping, hated, persecuted, rejected,

crippled, and even deceased. For Luke, the poor are “the neglected mass of humanity.”1

Each lesson will begin with a brief exegesis of the text with special attention

given to the uniquely Lukan aspects of the pericope. Following each exegesis, lesson

objectives outlining the goals of each lesson in light of the text and lesson activities that

could support the accomplishment of those objectives will be listed. The audience for

which this series is aimed consists of young adults.

Lesson Breakdown:

1. Luke 1: 46-55: Divine Reversal for the Rich and Poor

2. Luke 3:1-20: Repentance, Possessions, and Positions

3. Luke 6:27-3: The Expense of Loving the Enemy

4. Luke 12:13-21: Wealth and Self

5. Luke 12:22-34: Long Term Investments

6. Luke 14:7-14: Favors with Fine Print

7. Luke 14:25-34: Cost/Benefit Analysis

8. Luke 16:1-14: Spending Wisely

9. Luke 16:27-26: The Income Gap

10. Luke 19:1-10: You Are As You Spend

1

Joseph A. Fitzmeyer, The Gospel According to Luke (I-IX): Introduction, Translation, and Notes

(AB 28; Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday & Company, 1981), 250.

Pittman 2

Divine Reversal for the Rich and Poor: Luke 1:46-55

Exegesis and Lukan Emphasis:

Luke is the only gospel writer to record the four hymns in the birth narrative of

which the Magnificat is first.2 This hymn, replete with references to the LXX, connects

the work of Christ to the ongoing work of God in Israel’s history and sets the tone for

Luke’s message.3 The accumulation of allusions to God’s deliverance and acts of reversal

for Israel “forecasts a theme that Luke will develop . . . the dawning of the messianic age

reveals God’s continued deep regard for the widow, the orphan, the lowly, the hungry

and the poor.” The emphasis on wealth, poverty, and possessions in both permeates the

Old Testament and is seen anew in the teaching and ministry of Christ.4

Mary states six actions of God as gnomic aorists, indicating the timeless truth of

these divine activities.5 The connection between God’s activities and those of Christ is

communicated as well by the dual use of titles for both God and Christ.6 This passage

first introduces the centrality of service to groups in a “tapeivnwsin” in the ministry of

Christ (Luke 1:48).7 Such centrality becomes evident at the very inception of his ministry

in Luke 4:14-20. The blessings and woes of chapter 6:20-26 highlight again this reversal,

again including specific references to the poor and rich (6:20, 24). Twice Jesus warns his

disciples that those who seek to save their lives will ultimately lose them, while those

who lose their lives will be saved (9:24, 17:33). The theme of elevation of the lowly and

demotion of the mighty appears again and again in the ministry of Christ.

As the Magnificat states, God “has filled the hungry with good things but has sent

the rich away empty,” it introduces the theme of rich and poor (1:53). This passage will

be discussed not because it exclusively focuses on the issues of wealth and poverty but

because it provides the broader framework for Luke’s discussions. The care of the poor

has long been a part of God’s work of and his intention for his people. For the Christian

community, the care for the poor is not an optional activity.

Lesson Objectives

1. Investigate the significance of allusions to Old Testament history and themes.

2. Discover the presence of similar themes in the ministry of Christ.

3. Discuss the inclusion of wealth and poverty in the theme of reversal, with an eye

toward both personal implications and the proper activity for disciples.

2

See also songs of Zechariah, angels and Simeon (1:68-79, 2:14, 2:29-32). Magnificat is the Latin

translation of megaluvnei, the first word of the hymn. C.J. Martin, “Mary’s Song,” DJG, 525-526.

3

The style of the text strongly resembles that of the LXX due to prevalent Semiticisms. Luke

Timothy Johnson, The Gospel of Luke (SP 3; Collegeville, Minn.: Liturgical Press, 1991), 40. The hymn

contains no less than 35 allusions and appears to be modeled after the song of Hannah in I Sam 2:1-10. See

also songs of deliverance by Moses, Miriam, and Deborah (Ex 15:1-8, Ex 15:19-21, Judges 5:1-31).

Martin, “Mary’s Song,” 525. Such songs were likely sung in the life of faithful Jews in the period. Norval

Geldenhuys, Commentary on the Gospel of Luke: The English Text with Introduction, Exposition, and

Notes (NICNT; Grand Rapids, Mich.: William B. Eerdmans, 1979), 85.

4

Old Testament passages about God’s care for the poor include Deut 15:7-11, Lev 19:9-18, Is

1:12-17; Amos 2:6-7. Martin, “Mary’s Song,” 526.

5

epoivhsen, dieskovrpisen, kaqe/i:len, u{ywsen, ejnevplhsen, ejxapevsteilen

6

Titles include for God include “Lord,” “Savior,” and “Holy” (1:46, 47, 49). Christ was called

“holy” in 1:34 and “Lord” in 1:43, and will be called “Savior” in 2:11. Johnson, Luke, 44.

7

This is not a mental attitude; but a position of “poverty and powerlessness.” Johnson, Luke, 42.

Pittman 3

Lesson Activities

1. Convey the effect of the style and allusions by reading the KJV and discussing

biblical allusions in common parlance (the writing is on the wall, etc.).

2. Identify the six activities of God in 1:51-53; identify specifics instances of those

activities in Israel’s history.

3. Discuss the implications of the connection to Christ in the passage.

4. Identify and characterize the individuals or groups in the hymn and discuss which

character the church most reflects. Discuss implications for the ministry and lives

of Christians.

Repentance, Possessions and Positions: Luke 3:1-20

Exegesis and Lukan Emphasis

While all four gospels record the ministry of John the Baptist, only Luke records

his teachings about possessions in 3:1-20 (Matt 3:1-12, Mark 1:1-8, John 1:15-27). Luke

introduces John in his ministry as one “preaching (knruvsswn) a baptism of repentance

for the forgiveness of sins” (Luke 3:3). While Jews would have been familiar with the

concept of baptism, John’s baptism was revolutionary due to his assertion that Jewish

ancestry no longer sufficed for righteous status before God (3:8). The quote from Isaiah

40 subtly continues the reversal introduced in the Magnificat as “every valley shall be

filled in, and every mountain and hill made low” (3:5).8

John’s preaching consists of three sections: eschatological, ethical, and messianic

(3: 7-9, 10-14, 1-17). The first and final sections address primarily the coming judgment,

with the second focused more specifically on the coming Messiah.9 John emphasized the

production of fruit “in keeping with repentance.” Metanoiva appears twice, first in the

description of John’s baptism as a “bavptisma metanoivaV,” followed by the fruit

“ajxivouV th:V metanoivaV”(3:3, 8). Those failing to produce such fruit will be

destroyed.

In the middle ethical section, the three sayings address the type of fruit meant, and

are addressed to three distinct groups, each having asked “what should we do then?”

(3:10, 12, 14; see also the identical question in Acts 2:37). To the general crowd, John

responds with the command for all with two tunics or excess food to share with those

who lack (Luke 3:11). To the following two groups, the tax collectors and soldiers, John

forbids them to use their positions to extort money from others, and, in the case of the

solders, to be content with their pay (3:13-14).10 These admonitions, and their selection

8

“tapeinwqhvsetai” of 3:5 shares a root with “tapeivnwsin” of 1:48 and the “tapeinouvV” of

1:52.

9

The wrath of God indicates eschatological judgment. See also Luke 21:23, Rom 1:18, 2:5, 5:9; I

Thess 1:10; Matt 3:7. Johnson, Luke, 64. The “way of the Lord” John is preparing in 3:4 is connected to

the prophetic “Day of the Lord” (Isaiah 13:6, Ezekiel 13:3, Joel 1:15, Amos 5:20, Obadiah 1:15, for

example). Fitzmeyer, Gospel According to Luke (I-IX), 464. Only true repentance evident in the bearing of

appropriate works would stand in the Day of the Lord brought through his Messiah. Johnson, Luke, 66.

10

Tax collectors in Luke are typically responsive to John and Jesus (see Luke 5:27,29-30; 7:29-30,

34; 15:1-2; 19:2).

Pittman 4

from an apparently larger collection, indicates Luke’s “characteristic perception that the

use of possessions symbolizes one’s response to God’s visitation” (1:18).

Lesson Objectives

1. Briefly explore the history of baptism and its significance for the meaning of

John’s baptism

2. Note the placement of the ethical teachings after the call to produce fruit of

repentance, and the role of repentance in the passage.

3. Discuss the implications of the use of possessions as a baptismal response.

Discuss ways in which possessions could hinder repentance, as well as the

difficulty of this response.

Lesson Activities

1. As an introduction, invite the class to share the experience of their own baptism

and conversion. Use as introduction to the baptism of John.

2. Divide the class into three groups, asking them to trace these three themes through

the passage: judgment, possessions, and repentance. Discuss the ways in which

they are related.

3. Discuss the specific instructions of John, particularly related to the groups to

whom they were addressed. List implications for the church, addressing

specifically the acquisition of possessions.

4. Read the quote from Johnson regarding Luke’s “characteristic perception that the

use of possessions symbolizes one’s response to God’s visitation,” and ask if that

seems to be true. Why or why not?

Luke 6:32-36: The Cost of Loving Your Enemies

Exegesis and Lukan Emphasis

In Luke, as in Matthew, the command to love enemies comes within the context

of a larger block of teaching, known in Luke as the Sermon the Plain. The passage on

treatment of enemies follows the blessings and woes of Luke 6:20-26, which convey the

same idea of reversal seen in the Magnificat.11 The enemies of 6:27-26 who “hate” are

the same as those in 6:22 who “hate”.12 As the abuse comes “because of the Son of Man,”

it seems enemies are an expected feature of the disciple’s life and that the proper

treatment of them is an act of discipleship.

The passage divides easily into two sections. The first, 6:27-30, deals primarily

with love and kind treatment toward enemies and concludes with the command to “do to

others as you would have them do to you,” a command that both contradicts and corrects

11

Those “who hunger now” will be satisfied, just as God “fills the hungry with good things”

(6:21,1:53). While Matthew’s blessings are spiritual, Luke’s blessings and woes refer to physical

conditions. D.E. Garland, “Blessing and Woe,” DJG 77-81.

12

Luke 1:71 strengthens the connection between enemies and those who hate. 21:17 again states

that others will hate the disciples on account of Jesus.

Pittman 5

contemporary philosophies (6:31).13 When the Golden Rule appeared, it was typically

stated in the negative form: “What you do not wish done to you, do not do to others.”14 In

the teaching of Christ, passive avoidance becomes active approach, as Christ followers

are commanded to love all, even enemies outside of Christ. “Love” according to the

definition here, does not entail a feeling but a “gracious, outgoing, active interest in the

welfare of others,” the placement of others ahead of yourself.15

The second section, verses 31-36, opposes the patron-client relationship and

principle of reciprocity common in that society.16 No “cavriV” is earned by repaying

“debt” of a good deed done by another by acting in kind, for “even sinners love those

who love them” (6:28) Love of others requires a step beyond reciprocity. It is here that

Luke inserts his unique element, for “even sinners lend to sinners, expecting to be repaid

in full” (6:34). The insertion of this element adds an additional aspect of cost to love of

enemies. Disciples are to give of their prayer, their cloaks, and their financial resources

“without expecting to get anything back” or demanding any reciprocal action because

they are to imitate their Father “who is kind to the ungrateful and the wicked” (6:35-36).

The love of enemies is costly in every sense, but commanded nonetheless.

Lesson Objectives

1. Define enemy for Luke’s original audience and for us, with attention to presence

in daily life, experience with, and identity of those enemies.

2. Introduce the movement from passive response to active engagement, paying

attention to costly elements of such engagement.

3. Discuss the mention of possessions in this context, asking what it communicates

and what the implications of such inclusion are for church’s call to love enemies.

Lesson Activities

1. Discuss the context of Luke’s audience, with attention to enemies, as well as the

context of modern readers. Note the differences and similarities.

2. Write out Luke 6:31 and Rabbi Hillel’s statement. Identify the similarities and

differences in order to identify the significance of Christ’s reformulation.

3. List the costly elements of loving enemies included in this passage; having done

so, discuss the foundation of the command in the nature of God. Brainstorm

practical implications for loving enemies for people living in the relative presence

or absence of enemies.

Matthew notes that the disciples “have heard that it was said . . . hate your enemy,” indicating

that the principle was common at the time (Matt 5:43). Similarly, the Qumran commands followers to “hate

all the sons of darkness” who are outside of the community. L. Morris, “Love,” DJG 492-495. The Greek

philosopher Pericles urged that enemies should be overcome by acts of goodwill and generosity. Fitzmeyer,

Gospel According to Luke, 627.

14

The teaching of Rabbi Hillel. L.D. Hurst, “Ethics of Jesus,” DJG 210-222.

15

Hurst, “Ethics of Jesus,” DJG 217

16 F.W. Danker, “Benefactor,” DJG 58-60. “The ethics of reciprocity, a gift-and-obligation

system . . . tied every person . . . into an intricate web of social relations.” Joel B. Green, The Gospel of

Luke (NICNT; Grand Rapids, Mich.: William B. Eerdmans, 1997), 551.

13

Pittman 6

Luke 12:13-21: Wealth for Self

Exegesis and Lukan Emphasis

Luke alone records this encounter and parable, which together present the pursuit

of possessions as an inherently selfish and perhaps isolating endeavor. The parable is

introduced by request of a certain man in the crowd for Jesus to help him obtain his half

of the inheritance from his brother. No context for the demand is given; it is not clear

whether half the inheritance belonged to him by right.17 Such clarification is unimportant

for the message of the parable. In response, Jesus warns the crowd to “be on [their]

guard against all kinds of greed,” and proceeds to state the same message in story, for “a

man’s life does not consist in the abundance of his possessions” (Luke 12:15).

The frame largely determines the meaning of the parable; Luke 12:15 introduces

the rich man as the paragon of greed, and the conclusion indicates that he withheld from

God.18 Finally, Luke consistently uses “dialovgismoV” and “dialogivzomai” negatively,

each time in the context of a soliloquy (2:35, 5:21-22, 6:8, and 9:46-47).19 Most of the

speech in the parable occurs in the thoughts of the man and in his address to his own soul.

Personal endings or pronouns are used twelve times in the parable, as well as the five

second-person endings and pronouns in his address to his own soul. Only at the

conclusion does a second party, God coming in judgment, enter the picture.

The use of speech clearly indicates the focus of the man’s ultimate concern:

himself. In an agriculturally based economy characterized by a high level of

interdependence, “it is worth asking why this farmer lays out a course of action in

isolation from others.”20 The focus of the man on himself and his things becomes evident

as well in God’s question to him after he tells him his life is demanded of him: “Then

who will get what you have prepared for yourself?”(Luke 2:20). In his inward focus and

the laying up of goods for his own security and pleasure, he has failed to be rich toward

God. As a result, he is a fool who “lives completely for himself, he talks to himself, he

plans for himself, he congratulates himself.” Similarly, the man making the request

prompting the parable appears to place his own gain above his relationship with his

brother. But as Christ has stated already to his disciples, “What good is it for a man to

gain the whole world and yet lose or forfeit himself?” (Luke 9:25).21

Lesson Objectives

1. Introduce the frame of the parable in order to determine the relationship between

the frame and the parable, as well as the implications of such a relationship.

17

Green suggests that the man is the younger and therefore in need of outside assistance

Inheritance laws found in Num 27:1-11; 36:7-9; Deut 21:16-17. Green, The Gospel of Luke, 488.

18

Ibid., 489.

19

Johnson, Luke, 199. Green, The Gospel of Luke, 491.

20

Green, The Gospel of Luke, 490.

21

Fred B. Craddock, Luke (Int; Louisville, Ky.: John Knox, 1990), 163.

Pittman 7

2. Describe the character of the rich man, based on his life situation, motivations,

speech, and actions; brainstorm possible modern parallels, avoiding unnecessary

caricature.

3. Discuss what it means to be “rich toward God,” given the parable’s inherent

contrast to storing up for self.

Lesson Activities

1. Introduce the concept of the interpretive frame by discussing the effect of context

of the connotation of certain phrases. “That’s great,” for example, could be

positive or negative depending on what is one either side.

2. Have the class identify the characteristics of the rich man, looking for both

positive and negative aspects. Having identified the characteristics, discuss

possible parallels between the goals, aims, and actions of this man and others.

3. Discuss what “being rich toward God” means in terms of the parable. Brainstorm

ways in which we can be “rich toward God” in our own contexts.

Luke 12:22-34: Long Term Investments

Exegesis and Lukan Emphasis

While the majority of the passage is shared with Matthew 6:19-34, a few

important Lukan elements should be noted. First, the placement of these admonitions

and instructions after the parable of the rich fool in Luke 12:13-21 informs the

interpretation of this passage, as does the placement of the teachings about seeking the

kingdom after admonitions not to worry. Finally, the Lukan note about giving alms in the

context of seeking first the kingdom contributes to his teachings about the correct use of

possessions in kingdom life (Luke 12:33).22

Duplicate vocabulary and themes link 12:22-34 with 12:13-21. The preceding

parable provides the basis for the “dia; tou:to” introducing the following instructions

(12:21-22). The use of “yuxh:” and “favghte” in 12:22 tie the concerns of the crowd to

those of the rich man (12:19). Similarly, the crows do not engage in the type of

agricultural activity the rich man does; while the rich man’s fields “eufovrhsen,” the

birds do not “speivrousin oujde; qerivzousin,” and as a result do not have a “apoqhvkh”

to tear down to build bigger ones (12:16-18, 24). The man of the parable serves as a foil

for the correct attitude of the disciples, who are instructed to stop worrying, seeking

provisions, and fearing (12:22, 29, 32).23 Instead, disciples are to consider the birds and

wild flowers, to seek first the kingdom, to sell possessions, to give to the poor, and to

make purses that do not wear out (12:24, 27, 31, 33). In Luke’s gospel, the kingdom is

sought by resisting the need to hoard possessions in order to avoid worrying, for a sense

22

While Matthew gives instructions regarding giving to the poor in 6:1-4, the emphasis of his

instructions is the admonition to do so quietly.

23 The social and economic context highlights the difficulty of these commands; in a world of

subsistence farming, the search for the provisions necessary for life consumes people’s occupations;

reading the commands from the perspective of those on the lower end of the economic scale rather than the

middle class is necessary for grasping the difficulty in Christ’s words. Green, The Gospel of Luke, 492.

Pittman 8

of security, trusting God to provide since “oij:den oJvti crhvzete touvtwn,” and giving

to others instead (12:30).

Christ presents no simplistic teachings, for he does not deny the brevity of a life in

which a man’s life is demanded and grass is here one day and destroyed the next (12:21,

28).24 The point of the instructions is that those who store up their treasure in purses that

do not “wear out” will find that their hearts join it. The contrast between the storing up

of heavenly treasure and the giving away of possessions adds an additional level of

meaning. Eternal treasures do not accumulate by careful hoarding but by dispensing

possessions in a manner that reflects kingdom principles of care for the poor. As God was

pleased to give the kingdom, the disciples should give their possessions (12:32-33).25

Lesson Objectives

1. Present these well-known teachings with attention to the Lukan contrast between

storing up and giving away.

2. Discuss the effect of lifestyle and economic situation on the approach the wealth,

particularly with regard to achieving security (or the illusion thereof)

3. To consider the change in attitude necessary for such the outward flow of

possessions even in the midst of worry and stress.

Lesson Activities

1. Introduce the topic by discussing the current economic climate; what is it like,

what prompted the current issues, what the response of the country has been, etc.

2. Consider the effect of financial worry, particularly its effect on the use of

possessions.

3. Compare the acquisition of heavenly treasures with earthly ones. Use to prompt

discussion of secular and religious principles of economics.

4. Brainstorm ways in which treasures can be stored up in heaven according to the

principles of Luke 12.

Luke 14:7-14: Favors with Fine Print

Exegesis and Lukan Emphasis

This pericope, unique to Luke, communicates the use of possessions within the

context of a meal, a frequent setting for instruction in Luke (5:29-31, 7:36-50, 11:37-41,

14:1-24, 24:7-38). Luke’s use reflects the symposium tradition in which a meal was

followed by conversation and discussion. In this tradition, positions at the table indicated

the social status of the individual in relation to the host, a standing primarily determined

by economic standing.26 In the Mediterranean world, meals were an arena “in which

social values, boundaries, statuses, and hierarchies were reinforced;” in addition, issues

24

Johnson, Luke, 202.

Green, The Gospel of Luke, 494.

26

S. S. Bartchy, “Table Fellowship,” DJG 796-800. P.H. Davids, “Rich and Poor,” DJG 701-710.

25

Pittman 9

of reciprocity would have prompted people to host only those who could return the

favor.27 It is against this background that Christ’s teachings in 14:7-14 must be read.

The context of the instruction is a meal in the home of a Pharisee (14:1). Here

Jesus recasts social principles in light of heavenly values. The pericope consists of two

brief and parallel sections, instructions to the guests in 7-11, and instructions to the hosts

in 12-14.28 The endings of the instructions communicate the reframing of the values.

The first instructions, largely practical ones based on the danger of assuming a position at

a banquet higher than one allotted to you by the host, conclude with the phrase, “For

everyone who exalts himself will be humbled and he who humbles himself with be

exalted” (14:11). While practically true, in Luke it is also theologically significant. The

use of “tapeinw:n” connects this passage to the theme of reversal as related words appear

also in 1:48 and 1:52 in the Magnificat, as well as 18:14 in which the humbling and

exalting are clearly done by God. In a context in which peers do the exalting, Jesus states

“the only commendation one needs comes from the God who is unimpressed with such

social credentials.”29 In the instructions to hosts, the social principle of reciprocity is

reframed.30 The instruction is to invite “the poor, the crippled, the lame, the blind” rather

than “your friends, your brothers or relatives, or your rich neighbors” (14:12-13). Four

groups able to reciprocate are to be replaced by four who cannot. Instead, reciprocation

will come from God who “antapodoqhvsetai” (14:14).31 Christ’s commands call for an

end to “the distance between rich and poor, insider and outsider.”32

Lesson Objectives

1. Introduce the symposium tradition, the significance of meals in Mediterranean

culture, and the notion of reciprocity that set the background for the text.

2. Discuss the ways in which reciprocity functions in our own society as well as

ways in which we personally may tend to function along the same principles.

3. Discuss the way this passage applies to both socio-economic divisions and the

use of possessions in relationship to those divisions.

Lesson Activities

1. Investigate the role of reciprocity in current culture and relationships by

discussing the use of the phrase, “I owe you one.” Contexts for the use of this

phrase could include business, personal relationships, academics, etc.

2. Read the Magnificat and 18:4 with attention to the word “humble.” Use this

comparison to show the divine element to the practical instructions.

3. List ways in which socio-economic boundaries are reinforced in 21st century

culture in order to brainstorm ways that the church can break down those barriers.

Bartchy, “Table Fellowship,” 796.

The parallel constructions consists of each set of instructions beginning with “o{tan” with the

justification for the instructions introduced by “mhvpote” (14:8,12).

29

Green, The Gospel of Luke,552.

30

In the culture, “to accept an invitation was to obligate oneself to extend a comparable one.”

Green, The Gospel of Luke, 550.

31

The word by definition indicates the practice of reciprocity. Frederick William Danker, ed. A

Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament and Other Early Christian Literature (3d ed. Chicago:

University of Chicago, 200), 87.

32

Green, The Gospel of Luke, 553.

27

28

Pittman 10

Luke 14:25-33: Cost/Benefit Analysis

Exegesis and Lukan Emphasis

The majority of this pericope on counting the cost appears only in Luke. Matthew

does share the content of Luke 14:26, although his wording is somewhat gentler than

Luke’s, who states that disciples must “misei: to;n patevra eJautou: kai; th;n matevra.”

(Matt 10:37-38; Luke 16:26).33 Misew appears several times in Luke, perhaps most

informatively in 16:13; it is impossible to serve two masters because a man will “hate the

one and love the other, or he will be devoted to one and despise the other” (Luke 16:13).

“Hate” signifies a change in allegiance rather than “affective quality.”34 The call to

follow Jesus demands a level of allegiance greater than that expressed toward family.

Like those invited to the parabolic banquet, when the invitation to follow Jesus comes,

even family excuses are unacceptable (14:16-24).35

The careful consideration necessary to deciding to follow Christ is indicated by

the brief anecdotes about proper calculation before beginning, the first with regard to a

building project and the second with regard to a military endeavor (14:27-29; 30-32).

The results of failure for both are terrible. In the first case, the builder is mocked for their

inability to finish (14:29). In the second, the king in the end has to request a truce

(14:32). The passage also introduces three particular sacrifices that must be considered.

First, it calls for the turning away from mothers, fathers, and all family allegiance

(14:26). Next, it calls for self-denial through the carrying of the cross (14:27).36 Third, it

calls for disciples to leave behind, literally “bid farewell to” all possessions in order to

become a disciple (14:33). Once again, Luke connects the use of possessions with the

call to discipleship, including it here among a list of conditions for following Jesus.37

Discipleship, however, is not all cost. After the encounter with the rich man who

refused to sell his possessions and come follow Jesus, Peter reminds Jesus that the

disciples have given up “ta; i]dia” in order to follow Jesus. In response, Jesus assures

him that all who have given up possessions and family connections for the sake of the

kingdom will receive much more in return. For the disciples who “afevteV panvta

hkolouqhsavvn autw//,” Jesus again assures that such self-denial will result in “treasures

in heaven,” here stated as “ejn tw/: aijw:ni tw/ ejrcomevnw/ zwhvn aijwvnion” (5:11;

12:32; 18:30).38

Lesson Objectives

1. Discuss the connection between “hate” and allegiance in order to properly frame

the command of 14:26.

Matthew has instead “loves his father or mother more than me.”

Green, The Gospel of Luke, 565.

35

Johnson, Luke, 233.

36

While 14:27 does not contain the word deny, the parallel discipleship passage in 9:23-27

connects the carrying of the cross with self-denial.

37

For use of possessions see 8:3; 11:21; 12:15, 33, 44; 16:1; 19:8. Johnson, Luke, 230. See also

Fitzmeyer, Gospel According to Luke (X-XXIV), 1063.

38

Johnson, Luke, 279.

33

34

Pittman 11

2. Compare 14:25-33 with 9:23-27 and 9:57-62 in order to identify common themes.

3. Consider modern pledges of allegiance, such as loyalty to family, in order to place

the command to hate family within current context.

4. Discuss the role of costs and benefits in personal experiences of deciding to

follow Christ.

Lesson Activities

1. Have different people in the class read 14:25-33, 9:23-27 and 9:57-62 in quick

succession. Ask the class to identify the common themes between the passages,

in terms of both specific commands and larger principles.

2. Define “hate” in this context. Ask the class what goals or entities to which people

tend to pledge allegiance or loyalty. Use that list to prompt discussion over

situations in which those allegiances might detract from allegiance to Christ.

3. Discuss ways in which costs and benefits of discipleship should or should not be

taught to those considering discipleship by inviting class to share the factors of

their own decision.

Luke 16:1-13: Spending Wisely

Exegesis and Lukan Emphasis

The divisions of this pericope, unique to Luke, have proven difficult to determine.

It contains first a parable about a dishonest or unjust manager. While Fitzmeyer defines

the parable’s ending as verse 8a, the beginning of verse 9, “and I say to you,” most likely

the words of Christ, indicates that it should be connected to the parable as its

conclusion.39 Following the parable are a series of statements connected to the parable

primarily by the shared subject of wealth and possessions. These statements employ a

series of contrasts such as little/much, worldly wealth/true riches, hate/love, and

God/Mammon, in order to add to the message of the parable, namely that “how one

handles property has eternal consequences” (16:10-13).40

Troubling aspects of the parable, namely the questionable reduction of debts by

the manager, the commendation of a “dishonest” individual, and the use of wealth to gain

friends, are somewhat illuminated by features of the text and the cultural background.

The actions of the manager have been interpreted as both benign and unscrupulous.41 In

any case too many factors remain undefined to precisely determine how ethical the

manager’s actions were. Such determination is not the point of the parable, but rather the

“shrewd” use of the means available to secure his future.42 The use of “ajdikiva” and

“a[dikoV” in the statements following the parable alleviates some of the difficulty in the

39

Fitzmeyer, Gospel According to Luke (X-XXIV),1095. Craddock, Luke, 190.

Craddock, Luke, 190.

41

See Green, Gospel of Luke, 592 and Johnson, Luke, 244 for an expanded discussion.

42

Johnson, Luke, 244. Green notes as well that the parable is not intended to prompt the

identification of outside referents. Gospel of Luke, 589.

40

Pittman 12

commendation. Given the contrast drawn in 16:8 between the “sons of this age” and the

“sons of light,” it seems that Christ is using the example of worldly shrewdness with

possessions to illustrate that possessions can be used appropriately by disciples called to

store up “treasures in heaven” (16:8; 12:32). The commendation does not indicate that

these practical, worldly truths equal actions appropriate for disciples; the message is

instead that the disciples should be equally smart about using their possessions in a way

that positively affects their future.43 Possessions are not considered entirely distasteful by

Luke, for this passage indicates “for all the dangers in possessions it is possible to

manage goods in ways appropriate to life in the kingdom.”44 Those trustworthy with

“ajdikw/ mamwna/:” can be trusted with the true wealth of the kingdom (16:11).

Lesson Objectives

1. Interpret the parable in light of the contrasts present in 16;10-13.

2. Discuss the business principles present in the parable in order to compare and

contrast them to values for the church.

3. Based on the study of Luke so far, consider ways in which Luke suggests

possession should and should not be used to obtain security for the future.

Lesson Activities

1. Read the parable aloud, asking the class to yell “stop” when a perplexing aspect

of the parable is read. Use to prompt discussion about the nature of the parable

and the possible explanations for some of the difficulties.

2. Name some of the motivating values of the manager, such as the need for future

security evident through his measures to secure a place to life. Compare and

contrast those values first to secular values then to values within the church.

3. Brainstorm ways the church and the individuals within it can be “trustworthy in

handling worldly wealth” (16:11).

Luke 16:19-31: The Income Gap

Exegesis and Lukan Emphasis

Luke alone recorded the parable of the rich man and Lazarus, which paints in

vivid images the realization of the Lukan blessings and woes of 6:20-26, most clearly the

contrast between rich and poor. Both the rich man and Lazarus have their economic

status listed as a primary characteristic (6:20, 24; 16:27-28).45 In a more subtle way, the

story pictures the blessings and woes of the hungry and well fed (6:21, 25). Lazarus was

For Greco-Roman culture, “using money to make friends . . . refers simply to a social reality:

the exchange of money created, maintained, or solidified various forms of friendship.” Given the prevalent

practice of reciprocity, those whose debts were forgiven would have been obligated to return the favor.

Green, Gospel of Luke, 594. This parable is not the first time that Christ has used practical truths of culture

to indicate a higher truth for his followers; the practical instructions regarding banquets in 14:7-14 evidence

the same movement.

44

Craddock, Luke, 191.

45

The clothing or covering of the two individuals further indicates their contrasting conditions.

The purple clothing of the rich man indicates great wealth, while Lazarus is covered in sores. Green, The

Gospel of Luke, 605.

43

Pittman 13

“longing to eat what fell from the rich man’s table,” the scraps that would never be

missed in the apparent abundance (16:20). Finally, the parable reflects the present and

future states predicted by the blessings and woes. Jesus announces blessings for “you

who hunger now, for you will be satisfied (6:21, emphasis mine). Similarly, Abraham

points out to the rich man how “now [Lazarus] is comforted here and you are in agony”

(16:25, emphasis mine). Thus the parable vividly pictures the future fate of those who

are rich in the present. The physical and social distance between Lazarus at the gate and

the rich man at his table has been replaced by the “cavsma mevga” separating the rich

man in torment from Lazarus with Abraham (16:26). This story continues the reversal so

common in Luke, particularly given its location after the statement of 6:15 to the money

loving Pharisees: “What is highly valued among men is detestable in God’s sight.”

At the conclusion of the parable, the rich man asks Abraham to send Lazarus to

his brothers “so that they will not also come to the place of torment” (16:27).46 The rich

man has recognized now what he knows his brothers have not: they need to repent. The

parable provides a “warning to people like the brothers of the rich man. They face a

crisis in their lives and do not realize it.”47 Here, as in 3:1-20, repentance involves issues

of wealth and the proper use of it for the care of those in need.48 Abraham responds by

reminding him that his brothers have “the Law and the Prophets,” which command the

care of the poor (16:29; see also Ex 25:25-43; Ex 23:6; Deut 15:7-11). The issue at hand

is not obedience to a new or obscure law to the foundational laws of Jewish faith.

Repentance requires action. Those unwilling to follow the commands of the Law, the

Prophets, and the Lord regarding crossing the income gap to include and elevate the poor

find themselves on the wrong side of the chasm between paradise and torment. As Christ

stated in 13:5, “Unless you repent, you too will all perish.”

Lesson Objectives

1. Note the contrasts between Lazarus and the rich man, as well as the means by

which such contrasts are portrayed.

2. Investigate commands about care for the poor in the Jewish law in order to see the

presence of those commands in Jewish law.

3. Compare this passage to Luke 3:1-20 in order to emphasize again the eternal

consequences of the use of possessions.

Lesson Activities

1. Have one individual in the class read the blessings and woes of Luke 6:20-26.

Follow that reading by an immediate reading of 16:19-31. Use this pair of

readings to set this parable in the larger Lukan context.

2. Investigate some of the Old Testament commands regarding the care for the poor.

Discuss how they should have been seen in this parable.

46

Note how even here the rich man refuses to speak to a person of lower social status, even given

the reversed positions.

47

Joseph A. Fitzmeyer, The Gospel According to Luke (X-XXIV): Introduction, Translation and

Notes (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday & Company, 1981), 1128.

48 This is consistent with Luke’s “characteristic perception that the use of possessions symbolizes

one’s response to God’s visitation.” Johnson, Luke, 67.

Pittman 14

3. With the implications of those same commands for the rich man in mind, how

might those commands have implications for the community today.

Luke 19:1-10: You Are As You Spend

Exegesis and Lukan Emphasis

Luke is the only writer to record the encounter between Jesus and Zacchaeus, a

story that continues the emphasis on responsive tax collectors in contrast to the

unresponsiveness of many who give the appearance of righteousness (11:37-53, 18:1825). Tax collectors and sinners appear many times throughout the (3:12, 5:27,29-30;

7:29-30, 34; 15:1-2; 19:1-10). In at least two of these cases, 3:12 and 19:8, the response

of the tax collectors to the arrival of the kingdom is represented by their proper use of

their possessions; the tax collectors being baptized by John were told to deal honestly, a

principle present as well in Zacchaeus’s response. This positive portrayal of tax

collectors stands in direct contrast to view of them commonly held by the community.49

Perhaps the biggest textual question raised entails the use of the present tense

verbs “divdwmi” and “apodivdwmi.” One interpretation views them as future resolve,

indicating his intention to give the poor and repay those he cheated from that point on.50

It is also possible, however to interpret them as present progressives indicative of regular

practices.51 The “uJparcovhtwn” that Zacchaeus pledges to give to the poor are used in

contexts indicating both proper and improper use.52 While Jesus indicates no need for

repentance, it had never been a prerequisite for Christ’s association with anyone (5:31).

The use of “today” in the parallel statements in 19:5 and 9 bracketing Zacchaeus’s

response is important, as “today” in Luke frequently appears in contexts of salvation or

forgiveness of sins. (2:11, 4:21, 5:26, 13:32, 13:33, 19:5, 19:9, 23:43). In Green’s view,

the allusion to Ezekiel 34 in which God states his intention to “search for the lost and

bring back the strays” indicates that Jesus is bringing back into the community those like

Zacchaeus who have been mistreated by Israel’s leaders.53 While that may be true, the

“lost” in Luke also refer to the sinners that the Lord came to call to righteousness (5:32;

15:7, 10). In either case, whether Zacchaeus is continuing to use his possessions in a

manner appropriate for repentance or just resolving to do so, it is clear that the

“salvation” and his status as a child of Abraham entail the ways in which he uses his

T.E. Schmidt, “Taxes, ” DJG 805-807.

Green, Gospel of Luke, 671.

51

Ibid., 672.

52

The women following Jesus use their possessions to support his ministry, while the parable of

the rich man warns that “a man’s life does not consist of the abundance of his possessions.” See also

(11:21, 12:33, 12:44, 14:33, 16;1, 16:14, 19:8).

53

Green, Gospel of Luke, 673.

49

50

Pittman 15

wealth (19:9-10).54 Thus Zacchaeus stands in contrast to the rich ruler seen in 18:18-25

whose attachment to his possessions prohibited his entrance into the kingdom. He has

seen “swthriva,” while the rich ruler is unable “swqh:nai” (16:9, 18:26). Salvation is

evident precisely through use of possessions for obtaining them justly and giving them to

the poor.

Lesson Objectives

1. Consider the negative assumptions about tax collectors in Jewish society and his

estimation in the eyes of Christ.

2. Compare the responses of Jesus to the rich man and the rich man to Jesus to the

same responses is 19:10.

3. Provide backing and prompting questions for a hard look at the personal use of

wealth in light of Christ’s message in Luke’s gospel.

Lesson Activities

1. Read 5:29-30, 15:1-2, and 19:7; use readings to introduce the general perception

of tax collectors by Jews.

2. Discuss the attitudes of Zacchaeus as well as the rich man of 18:18-25 by

attending to their responses to Jesus presence and message.

3. Explore the implications of the connection between salvation and possessions

(with care to avoid the implication that salvation can be earned).

4. Conclude class with the following question: “In what ways does your wealth

indicate your salvation and membership among the community of Christ’s

disciples.”

54

Johnson, Luke, 286.

Pittman 16

Works Cited

Bartchy, S. S. “Table Fellowship.” Pages 796-800 in Dictionary of Jesus and the

Gospels. Edited by Joel B. Green and Scot McKnight. Downers Grove, Ill.:

InterVarsity Press, 1992.

Craddock, Fred B. Luke. Interpretation. Louisville, Ky.: John Knox, 1990.

Danker, F.W. “Benefactor.” Pages 58-60 in Dictionary of Jesus and the Gospels. Edited

by Joel B. Green and Scot McKnight. Downers Grove, Ill.: InterVarsity Press,

1992.

___________, ed. A Greek English-Lexicon of the New Testament and Other Early

Christian Literature. 3d ed. Chicago: University of Chicago, 2000.

Davids, P.H. “Rich and Poor.” Pages 701-710 in Dictionary of Jesus and the Gospels.

Edited by Joel B. Green and Scot McKnight. Downers Grove, Ill.: InterVarsity

Press, 1992.

Fitzmeyer, Joseph A. The Gospel According to Luke (I-IX): Introduction, Translation,

and Notes. Anchor Bible 28. Garden City: N.Y.: Doubleday & Company, 1981.

Fitzmeyer, Joseph A. The Gospel According to Luke (X-XXXIV): Introduction,

Translation, and Notes. Anchor Bible 28A. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday &

Company, 1985.

Garland, D.E. “Blessing and Woe.” Pages 77-81 in Dictionary of Jesus and the Gospels.

Edited by Joel B. Green and Scot McKnight. Downers Grove, Ill.: InterVarsity

Press, 1992.

Geldenhuys, Norval. Commentary on the Gospel of Luke: The English Text with

Introduction, Exposition, and Notes. New International Commentary on the New

Testament. Grand Rapids, Mich.: William B. Eerdmans, 1979.

Pittman 17

Green, Joel B. The Gospel of Luke. New International Commentary on the New

Testament. Grand Rapids, Mich.: William B. Eerdmans, 1997.

Hurst, L.D. “Ethics of Jesus.” Pages 210-22 in Dictionary of Jesus and the Gospels.

Edited by Joel B. Green and Scot McKnight. Downers Grove, Ill.: InterVarsity

Press, 1992.

Johnson, Luke Timothy. The Gospel of Luke. Sacra Pagina 3. Collegeville, Minn.:

Liturgical Press, 1991.

Marshall, L. Howard, ed. Moulton and Geden Concordance to the Greek New Testament.

6th ed. Edinburgh, Scotland: T & T Clark, 2002.

Martin, C.J. “Mary’s Song.” Pages 525-526 in Dictionary of Jesus and the Gospels.

Edited by Joel B. Green and Scot McKnight. Downers Grove, Ill.: InterVarsity

Press, 1992.

Morris, L. “Love.” Pages 492-495 in Dictionary of Jesus and the Gospels. Edited by Joel

B. Green and Scot McKnight. Downers Grove, Ill.: InterVarsity Press, 1992.

Orchard, Bernard. A Synopsis of the Four Gospels in Greek. Macon, Ga.: Mercer

University, 1983.

Schmidt, T.E. “Taxes.” Pages 805-807 in Dictionary of Jesus and the Gospels. Edited

by Joel B. Green and Scot McKnight. Downers Grove, Ill.: InterVarsity Press,

1992.