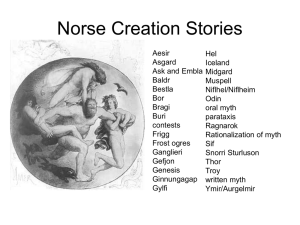

Snorri's Skaldskaparmal

advertisement

Snorri Sturluson • Snorri was born in Iceland in 1179 and died on the 22nd September 1241. • He was a descendent of the poet and warrior Egil Skallagrimsson, and probably composed the famous Egilssaga about his ancestor. • Snorri grew up in Oddi at the home of Jan Loptsson, at the time the most wealthy and influential chieftain in Iceland. He received the best possible education – Jan’s grandfather was Saemund the Learned, who had studied in Paris. Snorri Sturluson • Unlike the vast majority of medieval writers, Snorri was a political, rather than a religious figure. • Snorri belonged to a famous and powerful family, the Sturlungars, who gave their name to the chaotic period in Icelandic history in which Snorri lived. • Snorri began his career with a marriage to a wealthy woman, though he was soon separated from her and had many affairs during his life. Snorri Sturluson • Snorri held important offices during his life, including twice being elected Lawspeaker of Iceland (1215-18 and 1222-1231) and serving on the highest court in the country. • Snorri’s greed, ambition and cunning led him to make alliances with the King of Norway, and later to plot a rebellion against the king. • Snorri was assassinated by his former son-in-law on orders by the Norwegian King, in the cellar of his home in Reykholt in 1241. Icelandic History • Iceland is discovered by Norwegian sailors around 870; island inhabited only by Irish anchorites. • Settlement by Norwegians and others begins shortly afterward; the country is officially settled in 930, when the Althing is instituted. • 1000 A.D. Iceland converts to Christianity. • 1241 A.D. Death of Snorri. • 1262 “Voluntary Subjugation” of Iceland to Norway; prosperity of the island decreases greatly. • 1944 Icelandic Independence from Denmark. Snorri Sturluson • Snorri is one of the few known authors of medieval prose works in Iceland – most of the saga authors remain anonymous. • Snorri established a reputation as a poet and writer, in addition to his legal and political career. • Heimskringla, a history of medieval Scandinavia. • Olafssaga and (probably) Egilssaga. • Snorra Edda (1220), consisting of Gylfaginning, Skaldskaparmal and Hattatal, books dealing with the art of medieval Scandinavian court poetry. Snorri Sturluson • Snorri probably wrote his Edda because the art of the poet (Skald) was falling out of fashion or becoming increasingly archaic and difficult. • In contrast to the mythological poetry of the Elder Edda (e.g. Voluspa or Havamal), court poetry was complicated and intricate, depending on a shared body of lore for mutual understanding. • Skaldskaparmal (or “Language of Poetry”) is a discourse between Ægir (god of the sea) and Bragi (god of poetry) about the origin and language of poetry in Scandinavia. Skáldskaparmál • Snorri’s treatise on poetry deals in dialogue form with the mythic origins of poetry as well as with the various verse forms and the common phrases used. • He quotes verses from many authors who are otherwise unknown. • His explanations of kennings (from kenna eitt vio – to express a thing in terms of another) provide us with much mythological information that is available from no other source. Skáldskaparmál • Ægir comes from his island home (he is a sea god or giant) to visit the gods and goddesses in their hall while they are drinking. • He sits beside Bragi (whose name is related to the verb “to brag,” and who may have originally been a real person, the legendary poet Bragi Boddason, from the 9th century AD). • Bragi becomes a little drunk and starts telling stories, first the myth of the Theft of Idunn (59f.) • Giant Thiassi steals Idunn, but is tricked and killed. Skáldskaparmál • Bragi then relates the myth of Skadi and her search for compensation for the death of Thiassi, her father (61). • Bragi explains the division of the inheritance of Olvaldi, that each son in turn took a mouthful of gold – “and now we have this expression among us, to call gold the mouth-tale of these giants, and we conceal it in secret language or in poetry by calling it speech or words or talk of these giants.” • Ægir is impressed by this information and asks Bragi to explain the origin of poetry. Skáldskaparmál • Bragi relates that the Æsir and Vanir spit into a kettle to seal the truce after their war. They kept the spittle as a symbol of peace, but later used the magic liquid to fashion a man, who was named Kvasir, exceedingly wise and eloquent (61f.) • Kvasir traveled through the world, sharing his wisdom, but was treacherously killed by two dwarfs, Fialar and Galar. • The dwarfs mixed his blood with honey and brewed mead, which they put in vats named Odrerir and Son and Bodn (62). Skáldskaparmál • The mead made from Kvasir’s blood had the special property that whoever drank from it would speak poetry. • Fialar and Galar had a nasty Giant guest named Gilling, whom they drowned and whose wife they killed (by dropping a stone on her head). • Gilling’s son Suttung came for vengeance and they paid for their lives with the precious mead. • Suttung hid the mead in the mountain cave Hnitbiorg, putting his daughter Gunnlod in charge of guarding the vats. Skáldskaparmál • The mead of poetry is thus called: • Kvasir’s blood • Dwarf’s drink • Liquid of Odrerir or Bodn or Son • Dwarf’s transportation • Suttung’s mead • Liquid of Hnitbiorg • Fialar’s treasure or Galar’s ransom, etc. etc. • Ægir then asks, how the Æsir got hold of the mead of poetry? Skáldskaparmál • Odin set out on a quest to seize the mead of poetry from Suttung. • He came to a field where nine slaves were mowing hay; he sharpens their scythes and then asks if they would like his whetstone. Since they all wanted it, he threw it into the air – and they all slit each other’s throats fighting for it. (God of the Dead) • Odin, calling himself Bolverk (worker of evil) then goes to Baugi, Suttung’s brother, and offers to work in place of his dead slaves, in return for one draught of the mead. Skáldskaparmál • Baugi makes no promises, but agrees to talk with his brother about the requested payment. • Odin/Bolverk does the work of nine men during the summer and then asks for his payment. • He and Baugi go to Suttung, but he refuses even a single drop of the precious mead. • Bolverk takes out an auger named Rati and asks the Giant Baugi to bore a hole with it. Baugi drills two times, before Bolverk is satisfied that he has truly drilled through the mountain. Skáldskaparmál • Bolverk transforms himself into a snake, slithers through the hole into the mountain – Baugi tries to kill him with the auger, but is too slow. • In the mountain cave, Odin reassumes his shape and seduces the Giantess Gunnlod. He sleeps with her for three nights and then she lets him take three sips of the mead – Odin drains each vat. • Odin/Bolverk turns himself into an eagle and flies as fast as he can for Asgard. Suttung takes his own eagle shape and pursues him. When he nears Asgard, Odin spits the mead into vats (63f.). Skáldskaparmál • A little of the mead spills out, and that is called the “rhymster’s share” – for bad poets. • Odin bestows the mead on his favored mortals – poetry is thus a form of divine inspiration or intoxication associated with the wisest and craftiest of all the gods. • Odin’s booty or Odin’s find • Odin’s gift • Æsir’s drink Idunn and her golden apples Idunn being carried off by the Giant Thiassi Idunn and her apples, Idunn with Loki Odin with the Giantess Gunnlod, Drinking the Mead of Poetry Skáldskaparmál • The narration now assumes a “question and answer format” – very common in medieval pedagogical or philosophical texts. • The language of poetry (64) has three categories: • To call everything by its name • To use substitution • To use a description or periphrastic term, called a kenning. • Odin thus called Victory-Tyr, Hanged-Tyr or Cargo-Tyr Skáldskaparmál • Snorri justifies his explanation of these kennings – which should be obvious – because young poets need to learn the rich language of their ancestors. • Snorri is careful to remind his audience that “Christian people must not believe in heathen gods, nor in the truth of this account … (64f.) • Snorri presents a euhemeristic account of the settlement of the North by heroes of ancient Troy. • Snorri offers a novel interpretation of the Myth of Hymir (65f.), mixing Trojan and Norse heroes! Skáldskaparmál • An example of Norse verse (see 66): Now for *sea-steeds *trunks there is *Eagles’ flight over land in store – I guess they are getting *Hang-god’s *Hospitality and *rings. *ship’s *men (=Viking warriors) *eagles are massing over a battlefield *Odin’s *as his (slain) guests in Valhall *plunder Skáldskaparmál • • • • • • • • Some common kennings for poetry (70ff.): Kvasir’s blood, Dvalin’s drink, dwarf’s yeast-surf Dwarf’s ship, dwarf’s mead, giant’s mead Suttung’s mead, liquid of Odrerir, Bodn and Son Liquid of Hnitbiorg, Bodn’s wave or surf Odin’s booty, Odin’s find, Odin’s cargo or gift Mountain-kept liquid, pot-liquid of gallows-cargo Har’s (Odin’s) ale, stream of Mim’s friend (Odin) Skáldskaparmál • Some kennings for Thor (72-74): • • • • • • • • • Son of Odin and Iord (earth) Father of Magni and Modi and Thrud Husband of Sif Ruler and owner of Miollnir Defender of Asgard and Midgard Slayer of giants and troll-wives Killer of Hrungnir, Geirrod, Thrivaldi, etc. Lord of Thialfi and Roskva Enemy of the Midgard serpent Skáldskaparmál • • • • • • • • Some kennings follow for lesser gods: Baldr (74f.) Niord (75) Freyr (75) Heimdall (75f.) Tyr (76) Bragi, Vidar, Vali, Hod, Ull (all on 76) Loki (76f.): father of monsters, thief of giants, mother of Sleipnir, enemy of gods, maker of mischief, Sif’s hair-harmer, the bound one… Skáldskaparmál • Snorri relates more myths to explain the kennings he has just listed for various gods. • Myth of Hrungnir’s visit to Asgard and his duel with Thor and excerpts from the poem Haustlong (77-81). • Myth of Thor’s visit to Geirrod and excerpts from the poem Thorsdrapa (81-86). Skáldskaparmál Snorri lists a number of kennings for goddesses: • • • • Frigg (86) Freyia (86) Sif (86) Idunn – and here he cites extensively from the poem Haustlong – see Thor and Hrungnir – (86-88). Skáldskaparmál • Snorri then lists kennings for geographical and cosmological features: • • • • • The Sky–Ymir’s skull, toil of the dwarfs (88ff.) The Earth–Ymir’s flesh, bride of Odin (90f.) The Sea–Ymir’s blood, sea-king’s way (91ff.) The Sun–daughter of Mundilfæri, sister of moon The Wind, Fire, Winter, Summer (93f.) Skáldskaparmál • • • • Some kennings for Man (94) Woman (94) Gold (94f.) Why is gold called Ægir’s fire? Snorri relates this myth of Lokasenna, relating how gold was used to illuminate Ægir’s hall (95). • Snorri also relates that Ægir has a daughter called Ran who catches men in the sea. • Snorri relates that poets went even further, using terms associatively or allegorically (95). Some Images of Ran Some Images of Ran Skáldskaparmál • Why is gold called Sif’s hair? Snorri relates the myth of how Loki cut off Sif’s hair and was forced to find a replacement (96f.). • This myth also explain how the gods acquired some of their greatest treasures – Skidbladnir, Miollnir, Gungnir, Draupnir, Freyr’s golden boar. • The myth ends with Loki escaping decapitation, but he does have his lips sewn together with an awl and thread. Skáldskaparmál • What is the reason for gold being called Otter’s payment / Otter’s ransom? Snorri relates this myth, which is known from a number of other literary sources (99-100). • This is the famous myth that is used to explain the background to the Saga of the Volsungs (or in Germany, the Nibelungenlied). • The motif of the Cursed Ring (or cursed gold) is used in a number of later retellings, from Wagner’s Ring-cycle to Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings. Skáldskaparmál • What more is there to tell about the gold? • Snorri goes on to summarize the Saga of the Volsungs (100-105). The legendary poems from the Poetic Edda deal with aspects of this legend. • Part of the story is clearly myth, most of the story is fanciful romance or legend, and part of the story is based on historical information – King Atli and King Iormunrekk are figures from the Völkerwanderung, having lived nearly 1000 years before Snorri recorded this tale in writing. Skáldskaparmál • Why is gold called Frodi’s Mead? (106ff.) • Frodi, King in Denmark, bought two slave girls (giantesses) from Sweden – Fenia and Menia. • He set them to work with two magic millstones and told them to grind out gold and prosperity, but they ground out an army instead. • Frodi was defeated and killed; the sea-king Mysing set the girls to work grinding out salt– they ground too much and the boat sank. • “Song of Grotti” in Poetic Edda tells this myth. Skáldskaparmál • Why is gold called Kraki’s seed? (110ff.) • Snorri here discusses Hrolfs saga kraka (and poems of the saga), which we read in class. • Snorri tells the incident of Hrolf’s “christening” somewhat differently: Vogg indeed first called him “Kraki,” but as a young man, not in Sweden. • The adventure in Sweden is also different; in Snorri’s version, Adils owes Kraki payment for sending his champions to assist him in a battle against the King of Norway. Skáldskaparmál • • • • More kennings for silver and gold (113f.) Gold-Kennings for “man” (114f.) Gold-kennings for “woman” (115f.) How shall battle be referred to? (117f.) • Weather of weapons or shields, or of Odin • Clash or noise of weapons or shields • Hail or rain of arrows or stones or darts • How shall weapons and armor be referred to? • Many picturesque terms for weapons (118) Skáldskaparmál • Battle is also called “Hiadnings’ storm,” because of a battle between Hogni and Hedin, who had abducted King Hogni’s daughter Hild. (122f.) • Hild cannot stand to see either her husband or her father killed, so she uses her magic to return the dead men to life – whereupon they continue the battle. • In time, the dead men and their weapons become stones during the day, assuming their mortal and violent natures at night, in the Orkney islands. Skáldskaparmál • How shall a ship be referred to? (124ff.) • Horse, animal or ski of sea-kings or of the sea • Wave’s steed, bear of currents, ocean-otter • How shall Christ be referred to? (126f.) • Interesting that Christ and Christian subjects are assimilated into Norse poetry – sometimes in associations with pagan imagery. • Snorri then describes kennings for various ranks of nobility – emperors – kings – earls – lords – hersar, Grafen, barons – Holdar [heroes] – hirdmen and housecarls (128ff.) Skáldskaparmál • Snorri’s discussion of poetry then turns to other aspects of poetry – (non-periphrastic terms): • Rhyme and praise, rhapsody, encomium, eulogy • Other, less poetic terms are given for gods (133), heavens and heavenly bodies (133f.), for the earth itself (134f.), wolves, bears and other animals (135f.). • Snorri also lists common names of horses (136f.) and of serpents (137), livestock (137), birds (137f.)—ravens and eagles always referred to “in terms of blood or corpses.” Skáldskaparmál • What terms for the sea are there? (139ff.) • Snorri lists quite a few verses describing the sea, including Ægir and his wife Ran and their nine daughters (waves). • What terms for fire are there? (143ff.) • Snorri then discusses other non-periphrastic terms for: Times, Men and Kings, especially the legendary dynasties of Scandinavia, the Ynglings, Volsungs, Niflungs, Budlungs, Skioldungs and others. Skáldskaparmál • What terms are there for poets? (150f.) • At this point, Snorri’s book assumes the character of a poetic thesaraus (150-155), with terms for men and women and for parts of the body. • Snorri provides us with a lengthy catalogue of names of all sorts of mythological and legendary beings and things: • Kings, giants, troll-wives, Æsir, Æsyniur (goddesses), men, battle, swords, battle-axes, arrows, bows, armor (byrnie), sea, rivers, fish, ships, earth, livestock, and finally the heavens. Skáldskaparmál • What does Snorri’s book tell us about Norse poetry in general? • What does his book tell us about the culture in which he lived? • What were the priorities of the culture? • What sort of imagery dominates his book? • What did he think of his ancestry and history? • What is the role of the poet in this society? • What do you think the effect of his book was? • What did you learn from this book?