sACC Functional Connectivity in Geriatric Depression

advertisement

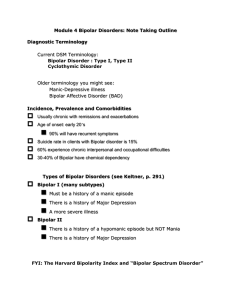

Bipolar d/o/Mania in Late Life Robert Kelly, MD Assistant Professor of Psychiatry Weill Cornell Medical College White Plains, New York Lecture available at www.robertkelly.us Financial Conflicts of Interest As faculty of Weill Cornell Medical College we are committed to providing transparency for any and all external relationships prior to giving an academic presentation. I do not have an interest in any commercial products or services—Robert Kelly, MD Outline • • • • Introduction Bipolar Disorders in The Elderly Differential Diagnosis Management Famous People with “Bipolar Disorder” Other “Bipolars” The list goes on….. Honore de Balzac, writer Charles Baudelaire, poet Ludwig von Beethoven, composer Marlon Brando, actor Albert Camus, writer Truman Capote, writer Jim Carrey, actor and comedian Ray Charles, R&B performer Frederic Chopin, composer Kurt Cobain, rock star Rodney Dangerfield, comedian Theodore Dostoevski, writer Larry Flynt, magazine publisher Michel Foucault, writer, philosopher Paul Gascoigne, athlete (soccer) Paul Gauguin, artist Bill Wilson, co-founder of Alcoholics Anonymous Ernest Hemingway, writer Robin Williams, Actor Audrey Hepburn, actress Sir Anthony Hopkins, actor Victor Hugo, author Andrew Jackson, U.S. President Kay Redfield Jamison, psychologist, writer Elton John, musician, composer Franz Kafka, writer Jessica Lange, actor Robert E. Lee, U.S. general John Lennon, musician Courtney Love, musician Imelda Marcos, Philippine dictator's wife Claude Monet, artist Marilyn Monroe, actor Boris Yeltsin, former President, Russia Virginia Woolf, writer Celebrity Meltdown, Psychology Today, December 1999, pp. 46-49,70,78 Bipolar Disorder in The Elderly By DSM-IV • Type I –the subtype most studied in the aged. • Type II- hypomania; seen in ambulatory populations; little data. Rapid cycling—no systematic study in elders. Bipolar Spectrum Disorders • Bipolar I – History of mania • Bipolar II – History of hypomania and major depressive episodes • Cyclothymia Hyperthymic temperament Secondary mania – to other illnesses or drugs Antidepressant-induced mania and hypomania = DSM-IV categories DSM-IV™. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994:317-391. Akiskal HS. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1996;16(2 suppl 1):4S-14S. Mood Disorder Criteria Distress or Impairment Clinically Significant “Abnormal” Involves Mood Elevated Expansive Irritable Depressed Manic Episode Elevated, Expansive, or Irritable DIGFAST Distractibility Involvement in pleasurable, risky activities Grandiosity Flight of Ideas Activity Increase Sleep not needed Talkative (pressured speech) One Week Not Mixed Episode Not Substance- or Treatment-Induced Not General Medical Condition Marked Impairment Hypomanic Episode Elevated, Expansive, or Irritable DIGFAST Distractibility Involvement in pleasurable, risky activities Grandiosity Flight of Ideas Activity Increase Sleep not needed Talkative (pressured speech) Four Days Unequivocal, Observable Change Not Substance- or Treatment-Induced Not General Medical Condition NOT Marked Impairment Major Depressive Episode Depressed Mood or Anhedonia Mood + SIGECAPS (most sx) Two Weeks Not Mixed Episode Not Substance-Induced Not General Medical Condition Not Bereavement Clinically Significant Distress or Impairment Mixed Episode Manic and Major Depressive Episode One Week Not Substance- or Treatment-Induced Not General Medical Condition Marked Impairment Mood Disorders, DSM-IV Mood Disorder Due to a General Medical Condition Substance-Induced Mood Disorder Adjustment Disorders Depressive Disorders Major Depressive Disorder Dysthymic Disorder Depressive Disorder NOS Bipolar Disorders Bipolar I Disorder Bipolar II Disorder Cyclothymic Disorder Bipolar Disorder NOS Schizoaffective Disorder Depressive Type Bipolar Type Mood Disorder NOS Mood Disorder Due to a General Medical Condition Prominent and Persistent Depressed Mood or Anhedonia Elated, Expansive, or Irritable Evidence Direct Physiological Consequence Not Due to Other Mental Disorder Not During Delirium Clinically Significant Distress or Impairment Substance-Induced Mood Disorder Prominent and Persistent Depressed Mood or Anhedonia Elated, Expansive, or Irritable Evidence Temporal--intoxication or withdrawal Etiologically Related Not Due to Other Mental Disorder Not During Delirium Clinically Significant Distress or Impairment Bipolar I Disorder Manic or Mixed Episode Major Depressive Episode Not Schizoaffective Disorder Not Superimposed on Psychotic Disorder Clinically Distress or Impairment Bipolar II Disorder Hypomanic Episode Major Depressive Episode Never Manic or Mixed Episode Not Schizoaffective Disorder Not Superimposed on Psychotic Disorder Clinically Distress or Impairment Schizoaffective Disorder Mood Episode + Schizophrenia Criterion A Mood, not anhedonia Bipolar or depressive types Schizophrenia-like period Two weeks No prominent mood symptoms Delusions or hallucinations Mood Episode “Substantial” Portion 40% or more Not Substance-Induced Not General Medical Condition Lifetime Prevalence Bipolar Disorders Bipolar I Disorder (0.4-1.6%) First manic/mixed episode very late in life Bipolar II Disorder (0.5% ??) Cyclothymic Disorder (0.4-1%) Bipolar Disorder NOS Symptom Domains of Bipolar Disorder Manic Mood and Behavior Euphoria Grandiosity Pressured speech Impulsivity Excessive libido Recklessness Social intrusiveness Diminished need for sleep Psychotic Symptoms Delusions Hallucinations Dysphoric or Negative Mood and Behavior Bipolar Disorder Depression Anxiety Irritability Hostility Violence or suicide Cognitive Symptoms Racing thoughts Distractibility Disorganization Inattentiveness Goodwin FK, Jamison KR. Manic-Depressive Illness. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1990:85-125. Differential Diagnosis of Mania • The differential diagnosis of manic and mixed states in late life is broad and includes: delirium, dementia, schizophrenia, bipolar (BP) disorders, schizoaffective disorder- BP type, drug intoxication, and mood disorder due to medical disorders or treatments. • Lack of detection and misdiagnosis are likely Additional Heterogeneity • BP elders have a broad range of clinical features, prior illness course, treatment history, comorbidity, functional status, psychosocial circumstances, and outcomes. • The heterogeneity includes additional ageassociated factors. Neurobiology of bipolar disorder • Meta-analysis of MRI Brain Morphometry Studies in Adults With Bipolar Disorder 26 studies comprising 404 patients • Compared volumetric brain measurements of patients with bipolar disorder with controls • Patients with bipolar disorder had enlarged right lateral ventricles compared with controls • Findings suggest that bipolar disorder is more likely to be associated with right-sided cerebral pathology McDonald C, et al. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;56:411-417. Mania and acute brain lesions • Stroke and other focal brain disease – especially right orbitofrontal and basotemporal areas Brooks et al Am J Psychiatry 2005 Mania in Neurological Disorders • Associations with other neurological disorders – Huntington’s Disease – Multiple sclerosis – Alzheimer’s disease—Confabulation versus Grandiosity Starkstein et al 1991; Shulman 1997 Bipolar Disorder and the Brain • New theory from Autopsy studies – mitochondrial malfunction • Mitochondria – vital organelle for energy production • Depletion of Mitochondria in autopsied bipolar brains; mutant mitochondrial DNA – two suspect genes Kato, University of Tokyo 2000 • Decreased expression of genes that coded for mitochondrial proteins in hippocampus of bipolar patients Christine Konradi Harvard and McLean Hospital, Archives of General Psychiatry 2004 Neurobiology of mania • Less studied than that of major depression • Current hypothesis posits deficient serotonergic neurotransmission as a pathophysiological cause of both depression and mania • In mania, neurotransmission may be related to GABA deficits • Without usual GABA functioning, unopposed relative increases in NE and DA activity may underlie the development and progression of mania • Hypothesis supported by efficacy of GABA agents in the treatment of mania Neurotransmitters and mania • Several neurotransmitters involved (SE, NE, Dopamine, ? Cortisol) • Increase dopamine transmission from the substantia nigra to the neostriatum increased sensory stimuli and movement. • Dopamine activity in the other two pathways, from the ventral tegmentum and the tubero-infundibular, remains unchanged in mania Berns and Nemeroff 2003 Secondary Mania • Antidepressant Associated Mania • Neurological disorders with mania as initial clinical presentation • Delirium (medications, drugs, infections, other…) Antidepressant Associated Mania • Controversial nature; can occur in elders • SSRIs involve less risk than TCAs? • Avoided by use of mood stabilizers • Can occur with ECT Bittman and Young 1991 Treatment • • • • Multidisciplinary approach +++ Medications Psychotherapies Psychosocial interventions Psychopharmacotherapy • Mood stabilizers • Atypicals • Others APA Practice Guidelines for Bipolar Disorder: First-Line Treatments • Manic/mixed episodes – Severe cases: combination therapy (lithium/divalproex + antipsychotic) – Mild to moderate cases: monotherapy (lithium, divalproex, or atypical antipsychotic) • Depressed episode – Lithium or lamotrigine monotherapy – Severe cases may require combination therapy • Maintenance: lithium, divalproex, or other agents (reasonable to continue same agent used to achieve remission) American Psychiatric Association. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(4 suppl):1-50. Mania and FDA • Currently FDA approved • lithium (Eskalith or Lithobid),divalproex sodium (Depakote), carbamazepine (Tegretol), • olanzapine (Zyprexa), risperidone (Risperdal), quetiapine (Seroquel), ziprasidone (Geodon), aripiprazole (Abilify) • At least one adequate well controlled study with positive data: haloperidol (Haldol) NAMI website 2007 Mood Stabilizers: Lithium Theory: Urea is related to mania, so urea salts may have a calming effect–John Cade, 1940’s Finding: Lithium urate made guinea pigs lethargic, but careful controls revealed that this appeared to be due to due to lithium rather than urea. New hypothesis: Lithium may be useful in treating the manic phase of bipolar disorder Finding: Lithium effective for Bipolar Disorder. Mood Stabilizers: Lithium • • • • For BP since 1960’s, FDA ‘74 Effective Antimanic, mood stab, BP depr. If Discontinued relapse near 100% 2 yr Therapeutic Levels: 0.6-1.5 mEq/ml – 0.3-0.8 in elderly – Same levels for prophylaxis – Narrow therapeutic index Mood Stabilizers: Lithium STRENGTHS • • • • “Gold standard” (for classic mania) Established efficacy in maintenance therapy Efficacy in augmenting antidepressants Suicide prevention WEAKNESSES • • • • • Less effective in rapid cycling and (?) mixed states Limited efficacy against depression? Slow onset of action Need for plasma-level monitoring Low therapeutic index American Psychiatric Association. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(4 suppl):1-50. Carney SM, Goodwin GM. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 2005;426:7-12. Nolen WA, Bloemkolk D. Neuropsychobiology. 2002;42 suppl 1:11-17. Swann AC, et al. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54:37-42. Goodwin GM, et al. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65:432-441. Mood Stabilizers: Divalproex STRENGTHS • • • • • Effective against mania Superior to lithium in mixed states Useful in comorbid substance abuse Can be started at a therapeutic dose Less cognitive dysfunction than lithium? WEAKNESSES • • • • • • • • Limited efficacy against depression? Weight gain and hair loss Teratogenesis Thrombocytopenia Polycystic ovary syndrome Pancreatitis Need for plasma-level monitoring Long-term efficacy not clearly established American Psychiatric Association. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(4 suppl):1-50. Albanese MJ, et al. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61:916-921. Gyulai L, et al. Neuropsychopharmacology.;180:23-32. 2003;28:1374-1382. Hirsch E, et al. Acta Neurol Scand Suppl. 2003 Stoll AL, et al. J Clin Psychiatry. 1996;57:356359. Polifka JE, Friedman JM. CMAJ. 2002;167:265-273. Mood Stabilizers: Carbamazepine WEAKNESSES STRENGTHS • • • Effective against mania Useful with comorbid substance abuse Relatively little weight gain • • • • Limited efficacy against depression? Complex pharmacokinetics (many drug-drug interactions) Lowers steroidal contraceptive blood levels Hyponatremia, agranulocytosis, Stevens-Johnson syndrome American Psychiatric Association. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(4 suppl):1-50. Weisler RH, et al. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:323-330. Goldberg JF, et al. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60:733-740. Goldberg JF, Citrome L. Postgrad Med. 2005;117:25-26, 29-32, 35-36. Wilbur K, Ensom MH. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2000;38:355-365. Extended-Release Carbamazepine: Efficacy in 239 Hospitalized Manic or Mixed Episode Patients 0 -2 YMRS Scores Baseline PBO = 27.93 CBZ = 28.46 -4 -6 -8 -10 End Point PBO = 20.82 CBZ = 13.38 -12 -14 -16 -8.0 * 0 Mean Change in HAM-D Score (LOCF) Mean Change in YMRS Score (LOCF) Reduction in YMRS Total Scores Reduction in HAM-D Total Scores -1 -1.5 End Point PBO = 8.47 CBZ = 6.88 -2 -2.5 -3 PBO (n=115) HAM-D Scores Baseline PBO = 9.45 CBZ = 9.60 -0.5 -1.7 † CBZ (n=120) *P <.0001; †P <.01. CBZ = carbamazepine; HAM-D = Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; LOCF = last observation carried forward; PBO = placebo; YMRS = Young Mania Rating Scale. Weisler RH, et al. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:323-330. Mood Stabilizers: Lamotrigine STRENGTHS • Effective as depression prophylaxis and (to a lesser extent) as mania prophylaxis • Little cognitive dysfunction • Generally well tolerated, little or no adverse effect on weight WEAKNESSES • Acute antidepressant effect less established • Very slow titration rate • Drug interactions (eg, valproate, carbamazepine, OCs) • Rash, Stevens-Johnson syndrome American Psychiatric Association. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(4 suppl):1-50. Goodwin GM, et al. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65:432-441. Goldberg JF, Burdick KE. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62(suppl 14):27-33. Bowden CL, et al. Drug Saf. 2004;27:173-184. Sabers A, et al. Neurology. 2003;61:570-571. Lithium vs Carbamazepine • 2.5-year study; N = 171 patients with bipolar disorder • Lithium statistically superior to carbamazepine in “classical” euphoric bipolar I disorder, but less well tolerated • Carbamazepine better than lithium for moodincongruent, atypical, non classical bipolar disorder • Patient satisfaction statistically higher in carbamazepine group Kleindienst N, Greil W. Neuropsychobiology. 2000;42(suppl 1):2-10. Atypical Antipsychotics for Bipolar Mania • Recommended both as monotherapy and as combination therapy with a mood stabilizer1-3 • Base selection on4 – – – – 1. 2. 3. 4. Efficacy Onset of action Safety and tolerability profile Individual patient factors: history, characteristics, prior response American Psychiatric Association. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(4 suppl):1-50. Suppes T, et al. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:870-886. Yatham LN, et al. Bipolar Disord. 2005;7(suppl 3):5-69. Keck PE Jr. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(suppl 3):5-11. TIMA Treatment Algorithm for Acute Hypomanic/Manic/Mixed Episodes in Patients With Bipolar I Disorder Stage 1 Euphoric Mixed 1A: Li, VPA, ARP, QTP, RIS, ZIP 1A: VPA, ARP, RIS, ZIP 1B: OLZ or CBZ Monotherapy Nonresponse: Try Alternate Monotherapy Response 1B: OLZ or CBZ Response CONT Partial Response Partial Response ARP = aripiprazole; CBZ = carbamazepine; CONT = continuation; Li = lithium; OLZ = olanzapine; QTP = quetiapine; RIS = risperidone; TIMA = Texas Implementation of Medication Algorithms; VPA = valproate; ZIP = ziprasidone. Adapted with permission from Suppes T, et al. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:870-886. Nonresponse: Try Alternate Monotherapy TIMA Treatment Algorithm for Acute Hypomanic/Manic/Mixed Episodes in Patients With Bipolar I Disorder cont. Stage 2 Li, VPA, AAP Choose 2 (not 2 AAPs, not ARP or CLOZ) Two-Drug Combination Response CONT Partial Response or Nonresponse Stage 3 Li, VPA, AAPs, CBZ, OXC, TAP Choose 2 (not 2 AAPs, not CLOZ) Two-Drug Combination Response Partial Response or Nonresponse Stage 4 CONT ECT or Add CLOZ or Li + [VPA or CBZ or OXC] + AAP AAP = atypical antipsychotic; ARP = aripiprazole; CBZ = carbamazepine; CLOZ = clozapine; CONT = continuation; ECT = electroconvulsive therapy; Li = lithium; OXC = oxcarbazepine; TAP = typical antipsychotic; TIMA = Texas Implementation of Medication Algorithms; VPA = valproate. Adapted with permission from Suppes T, et al. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:870-886. Risks Associated With Antidepressant Use in Bipolar Depression • Antidepressant monotherapy (eg, TCAs, MAOIs, SSRIs, SNRIs) are associated with risk of – Mania induction – Cycle acceleration • SSRIs and bupropion may be relatively safer with regard to these risks than TCAs El-Mallakh RS, Karippot A. Psychiatr Serv. 2002;53:580-584. Wehr TA, Goodwin FK. Am J Psychiatry. 1987;144:1403-1411. Vieta E, et al. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63:508-512. ECT ECT ECT • Effective in manic and mixed episodes, and in BP depression • Can be used in pharmacologically refractory or intolerant patients, and in severe cases • Clinicians have often used bilateral electrode placement in younger manic/mixed patients; efficacy of high dose unilateral ECT awaits study in elders • Many clinicians avoid using lithium during ECT Psychotherapies • • • • Family-focused Interpersonal and social rhythm Cognitive-behavioral Life goals program Psychosocial Interventions Goals • Improve medication adherence • Medicationminimize side effects, complexity, cost Reduce recurrences • Improve psychosocial functioning • Improve occupational functioning • Improve quality of life Education • Availability and support Continuation and Maintenance Treatment • Psychoeducation and social support are especially important in long-term management. • Continuation treatment--mood stabilizers usually maintained at stable doses for > 6 mo. • Maintenance pharmacotherapy – Indications and optimal conditions poorly defined in the elderly; – Prolonged exposure to antidepressants should be avoided if feasible; the same is true of antipsychotic cotherapy.