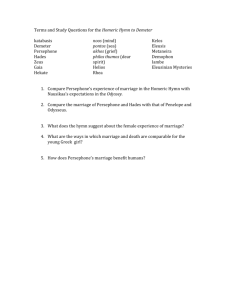

CH 27 Demeter and the Homeric Hymn to Demeter

advertisement

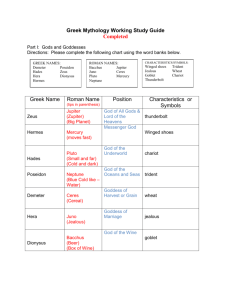

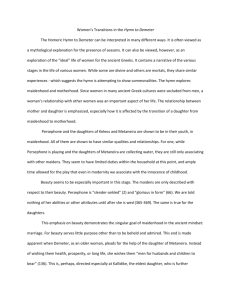

Chapter 27 Demeter and Persephone: The Homeric Hymn to Demeter The Hymn to Demeter • Was a “working version” of a myth. • Used at ceremonies in honor of the goddess held at her shrine in Eleusis, a town near Athens in Greece. • Composed before the end of the seventh century B.C.E. (699–600 B.C.E.). • Explains the significance of Eleusis: It was the place Demeter came to when she went to earth to look for her daughter Persephone. The Eleusinians built a temple for Demeter, and thus her visit led to the origin of her worship there. • The main celebration took place in early autumn, when the drought of summer was ending and the fields were becoming green. Theology • Demeter is the Greek goddess of grain and agriculture. She is worshipped with her daughter Persephone or Κόρη (Kore, “girl”), who represents the life force of the grain and disappears from the earth when the seed is put into the ground to die (as seed) and be born again (as grain). • Frazer suggested that since Demeter revitalizes the seed, she became associated with giving new life to the dead. This would explain her association in this story with Aidoneus (Hades), the god of the dead, which makes her the death god’s mother-in-law. • Demeter’s worship at Eleusis promises an afterlife to initiates The Style of the Poem • The Hymn to Demeter was composed in the style of Homer. • Homer was an oral poet who would perform his works from memory or create them on the spot for his audience. • He used modular units called “formulas” for building his poems. • Each time a poem was performed, it would be slightly different, because the poet would build it according to his moods and the response of his audience. • Examples of the formulas used in the poem: – “Lovely haired” describes Demeter. – “Slender-ankled” describes Persephone. – “Far-seeing and loud-thundering” describes Zeus. – The story also repeats longer sections, like “the many-named son of Kronos carried her away against her will.” Greek Gender Gap and the Hymn to Demeter • Helene Foley states that “[t]he Hymn repeats the pattern of sexual tensions among male and female deities found in Hesiod and prefigures the similar tensions that pervade Aeschylus’ Oresteia” (116). • The Hymn portrays the struggle of the mother, Demeter, to hold on to her child against the wishes of the father. Ultimately, Demeter has to give in to Zeus’ “patriarchal agenda” (Foley 169), but both the Hymn and the ritual at Eleusis give elaborate testimony to the power of her resistance and, as a result, to her limited autonomy. • Clay notes that “As a whole the Hymn to Demeter may be understood as an attempt to integrate, and hence to absorb, the cult of Demeter and the message of Eleusis into the Olympian cosmos” (265) represented by the poetry of Homer and Hesiod. Greek Marriage Customs • Greek women and men entered marriage at very different ages. • Men tended to marry when they had already established themselves, at 30 or so. • Women, on the other hand, married near menarche, the start of their menstrual period, at the age of 14 to 16. The Story of Persephone as a Marriage • Persephone is betrothed by her father Zeus to his brother Aidoneus/Hades. • She is not consulted; her intended husband is old enough to be her father. • Vase paintings and statues from the time period of the Hymn often portray Aidoneus/Hades and Persephone as a loving couple, the king and queen of Hades. Demeter is also portrayed as blessing their marriage. • The Hymn gives us much the same perspective. Near the beginning of the story, Helios tells Demeter, who is distraught at the loss of her daughter, “Not an unseemly bridegroom among immortals is Aidoneus/Hades, Lord of Many.” The Story of Persephone as a Marriage • Near the end, Aidoneus/Hades tells Persephone, “I shall not be an unfitting husband among the immortals, as I am father Zeus’ own brother. When you are here you shall be mistress of everything which lives and moves; your honors among the immortals shall be the greatest, and those who wrong you shall always be punished, if they do not propitiate your spirit with sacrifices, performing sacred rites and making due offerings” (p. 399). • Rhea, Demeter’s mother, tells her, “Come and do not nurse unrelenting anger against Kronion (Zeus), lord of dark clouds; Soon make the life-giving seed grow for men” (p. 401). Modern Feminist Views of Demeter and Persephone • The story attaches value to women and their emotions. • The Hymn is an account of rape, which represents the intrusion of men into the peaceful lives and loves of women, the triumph of patriarchy, and the limitation of religion based on the feminine principle. • Gimbutas would regard the myth as reflecting remnants of Great Goddess worship in Pre-Indo European society. • Other feminist interpretations do not necessarily regard the myth describing a historical period. Instead, the myth may be used to explore gender dynamics under patriarchy and the ways in which women may resist having their relationships defined by attaching more importance to interactions between women. What Kinds of Insights Does the Myth of Demeter and Persephone Provide? • The myth explains the origin of worship at Eleusis and the basis for building a temple there. • We see the importance of Eleusis as an agricultural state, which is why it could resist being completely swallowed up in the Athenian empire. • Persephone goes down into the underworld and comes back, thus conquering death. Her triumph over death suggests that human beings can also, to some extent, overcome death. • The myth explains the origin and the significance of the seasons. The science of the time understood, as we do today, that certain meteorological conditions are necessary for the seed to grow. Aetiological Historical Metaphysical Cosmological What Kinds of Insights? • Although the marriage to Aidoneus causes grief to Persephone and Demeter, the story shows that the girl and her family adjust to it. • The myth shows us the grief of Persephone and of Demeter, but it also shows us that the girl eventually comes to accept her husband, at least in a limited way. • We see both the subservience of women to men in Athenian society and the basis of what can be their terrifying strength in resisting and defying the decisions of men. Sociological Psychological Anthropological