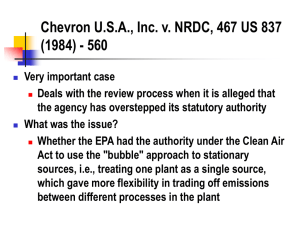

Legislation and the Regulatory State

advertisement