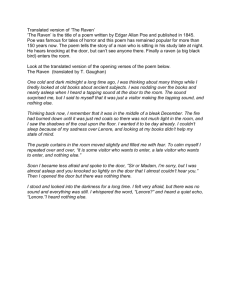

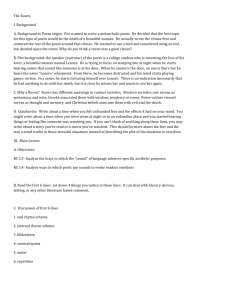

The Raven Setting

advertisement

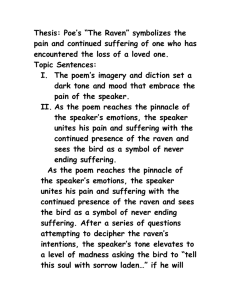

The Raven is made up of 18 stanzas of six lines each. Generally, the meter is trochaic octameter – eight trochaic feet per line, each foot having one stressed syllable followed by one unstressed syllable. Edgar Allan Poe, however, claimed the poem was a combination of octameter acatalectic, heptameter catalectic, and tetrameter catalectic. The rhyme scheme is ABCBBB, or AA, B, CC, CB, B, B when accounting for internal rhyme. In every stanza, the 'B' lines rhyme with the word 'nevermore' and are catalectic, placing extra emphasis on the final syllable. The poem also makes heavy use of alliteration Poe based the structure of The Raven on the complicated rhyme and rhythm of Elizabeth Barrett's poem "Lady Geraldine's Courtship". Poe had reviewed Barrett's work in the January 1845 issue of the Broadway Journal and said that "her poetic inspiration is the highest – we can conceive of nothing more august. Her sense of Art is pure in itself." As is typical with Poe, his review also criticizes her lack of originality and what he considers the repetitive nature of some of her poetry. About "Lady Geraldine's Courtship", he said "I have never read a poem combining so much of the fiercest passion with so much of the most delicate imagination." The Raven Lines 1-6 Once upon a midnight dreary, while I pondered, weak and weary, Over many a quaint and curious volume of forgotten lore – While I nodded, nearly napping, suddenly there came a tapping, As of someone gently rapping, rapping at my chamber door – "'Tis some visitor," I muttered, "tapping at my chamber door – Only this and nothing more." Poe jumps right in here and begins to create the atmosphere that is so important in this poem. In the first two lines, we find out that it's late on a "dreary" night, and that our speaker is reading weird old books and feeling "weak and weary." Do you get a feeling for this already? Do you know those nights where you're tired and maybe a little depressed, but you can't quite go to sleep? You turn things over in your mind, and as you do, you start to feel worse? Maybe you're reading a scary book or watching a spooky movie, and suddenly the whole world seems a little dark and scary? That's exactly where Poe wants to put us. In line 3, the speaker is just starting to nod off, and then…tap, tap, tap. Just a little noise, but suddenly he's jolted awake, and he's a little nervous. He tries to calm himself down, telling himself that "tis some visitor" (6) who has dropped by unexpectedly. But, just like in a horror movie, we know it won't be that easy. Lines 7-12 Ah, distinctly I remember it was in the bleak December; And each separate dying ember wrought its ghost upon the floor. Eagerly I wished the morrow; – vainly I had sought to borrow From my books surcease of sorrow – sorrow for the lost Lenore – For the rare and radiant maiden whom the angels name Lenore – Nameless here for evermore. Just as we're wondering whom that visitor might be, as we start to feel the suspense, Poe steps back. He almost starts the poem over again, telling us a little bit more about the speaker and more about that already spooky atmosphere. In line 6, we find out that not only is this a dark, late, dreary night, but it's December too. Poe is really piling it on here: dark, late, cold, and "bleak." It sure doesn't sound like anything happy is going to pop up here. Even the fire is going out, and the last coals, the " dying embers," are making creepy, ghost-like shadows on the floor (8). The room almost starts to feel haunted, and in a way, it is. In the next four lines we learn that there's a reason why our speaker is sitting up late, trying to distract himself with these old books. He's grieving for a lost woman, someone named Lenore. This woman (His wife? His girlfriend?) is among the angels and has left him behind, alone. He hopes for an end to the pain, what he calls "surcease from sorrow" (10), but maybe staying up and reading late in December isn't the best way to get your mind off of a loved one's death. Lines 13-18 And the silken, sad, uncertain rustling of each purple curtain Thrilled me – filled me with fantastic terrors never felt before; So that now, to still the beating of my heart, I stood repeating, "'Tis some visitor entreating entrance at my chamber door – Some late visitor entreating entrance at my chamber door; – This it is and nothing more." In fact, it seems like the room and its creepy atmosphere might really be getting to our speaker. Even the rustling sound of the curtains seems sad to him (13). As he listens, he begins to really freak out, his head filling with "fantastic terrors." His heart starts to beat faster too; to calm himself down, he has to tell himself (twice) that the knocking sound he hears is just a visitor. The more he says it though, the more we all know that it can't just be that, or at least not the kind of visitor he might be expecting… Lines 19-24 Presently my soul grew stronger; hesitating then no longer, "Sir," said I, "or Madam, truly your forgiveness I implore; But the fact is I was napping, and so gently you came rapping, And so faintly you came tapping, tapping at my chamber door, That I scarce was sure I heard you" – here I opened wide the door; – – Darkness there and nothing more. Eventually, he gets a hold of himself: "presently my soul grew stronger" (19). He calls out to the visitor he imagines must be there, and apologizes for taking so long. He explains that he was almost asleep and wasn't sure if he was just hearing things (20-23). Then, suddenly, he throws open the door and finds…nothing. Just the black night: "Darkness there and nothing more" (24). Poe is really keying up the suspense now. Again, it's hard for us not to think of a horror movie, where the nervous main character walks up to a door, slowly turns the knob, and finds nothing. That's always the sure sign that the surprise is coming, and when we least expect it. Lines 25-30 Deep into that darkness peering, long I stood there wondering, fearing, Doubting, dreaming dreams no mortal ever dared to dream before; But the silence was unbroken, and the stillness gave no token, And the only word there spoken was the whispered word, "Lenore?" This I whispered, and an echo murmured back the word, "Lenore!" – Merely this and nothing more. For a while, then, he's almost hypnotized by the darkness. He stares out into it, "peering […] fearing" (having fun with the rhymes yet?). Now might be about the time that you realize that our narrator isn't in great shape. He could close the door and go back to his book or his nap like a normal person, but he's clearly looking for something else. His mind is filled with strange ideas and terrible dreams (26). More than anything, though, he's obsessed with one idea, or, we should say, with one person. Suddenly, out of the total dark and quiet, we hear her name, "Lenore." Just that name, appearing in an eerie whisper out of nowhere (28). Or at least it seems like it comes from nowhere. In the next line, we find out that it is the speaker who has whispered her name, and just an echo that has "murmured back" the word "Lenore." For our depressed, grief-stricken narrator, the whole world seems bleak and terrifying, and everything, even the darkness, reminds him of his lost love. Lines 31-36 Back into the chamber turning, all my soul within me burning, Soon again I heard a tapping somewhat louder than before. "Surely," said I, "surely that is something at my window lattice; Let me see, then, what thereat is, and this mystery explore – Let my heart be still a moment and this mystery explore; – 'Tis the wind and nothing more!" Finally, he turns away from the darkness, but it's clear that he isn't comforted at all; in fact, he's feeling worse than ever: "all my soul within me burning" (31). This is a story about a guy in a room, but also about the mind: what it can do to us when it's off-kilter and all the feelings and ideas it can create. Our speaker, with his burning soul, is going through some rough times here. Then he hears the tapping again. Like anyone who is near the edge, he tries to get a grip, to come up with a rational explanation. He decides the sound is coming from the window, and he forces himself to go take a look. He tells himself to calm down again: "let my heart be still a moment" (35). In a final effort to make things seem normal, he tells himself it's just the wind (36). Line 37-42 Open here I flung the shutter, when, with many a flirt and flutter, In there stepped a stately Raven of the saintly days of yore; Not the least obeisance made he; not a minute stopped or stayed he; But, with mien of lord or lady, perched above my chamber door – Perched upon a bust of Pallas just above my chamber door – Perched, and sat, and nothing more. Here it comes! You knew from the title that there was a raven in here somewhere. Now, in the first two lines of this stanza, it shows up. And not just any raven, but a really impressive, capital-R kind of Raven. A "stately" (that just means royallooking) raven, one that makes the speaker think of older, nobler times, "the saintly days of yore" (38). This important-looking raven just prances in through the window. He doesn't even stop to say hi or to make a gesture of greeting (that's an "obeisance") to our speaker (39). He acts like an aristocrat ("with the mien of lord or lady") and doesn't waste any time making himself right at home. (40). In fact, he heads straight for that chamber door we've heard so much about and sits above it, on a statue. That statue is actually pretty important, and Poe definitely wants us to notice it, so let's take a moment to check it out. He describes it as a "bust" which is a statue that goes from the head to the middle of the torso. It's a statue of Pallas, another name for the ancient Greek goddess Athena. She is known primarily as a goddess of Wisdom. When a major symbol like this shows up, we know to be on our guard. It's a lot different from the speaker saying, "the raven perched upon my crappy old lamp," or something like that. Poe might be trying to get us to think about whether this bird is wise or not, whether it's a thinking thing or just a mimic. Lines 43-48 Then this ebony bird beguiling my sad fancy into smiling, By the grave and stern decorum of the countenance it wore, "Though thy crest be shorn and shaven, thou," I said, "art sure no craven, Ghastly grim and ancient Raven wandering from the Nightly shore – Tell me what thy lordly name is on the Night's Plutonian shore!" Quoth the Raven "Nevermore." At first, our speaker seems rather amused by his unexpected visitor. Poe gets a little fancy when he describes the raven, so we'll break it down: "Then this ebony [really black] bird beguiling [distracting him, capturing his attention] my sad fancy [imagination] into smiling,/By the grave [serious] and stern [serious again] decorum [proper way of acting] of the countenance (look on its face) it wore" (43-44). Fancy words aside, you might recognize this feeling. You're feeling down about something, and suddenly the sight of something strikes you as funny, and pulls you out of your funk a little. Our speaker really gets into this feeling of amusement, talking to the raven as if it were some noble person. He also goes out of his way to throw in some flourishes. The bit in line 45 refers to the way that a cowardly (craven) knight would sometimes have his head (crest) shaven to humiliate him. "Plutonian," in line 47, refers to the Greek god Pluto, who rules the Underworld. The adjective is meant to make us think about dark, scary, hellish things, like this particular dark, dreary night. If you're keeping score, that's two Greek god references in seven lines. We're starting to feel like our speaker might be a touch on the pompous side. All he really wants to know is the Raven's name. Of course the really big deal in this stanza doesn't come until the last line. The speaker runs his mouth with this jokey question and then, amazingly, the Raven answers him. He only speaks a single word: "Nevermore" (48). Lines 49-54 Much I marvelled this ungainly fowl to hear discourse so plainly, Though its answer little meaning – little relevancy bore; For we cannot help agreeing that no living human being Ever yet was blest with seeing bird above his chamber door – Bird or beast upon the sculptured bust above his chamber door, With such name as "Nevermore." The speaker is more than a little surprised to hear this bird talk (49), but he doesn't really see how "Nevermore" answers his question (50). He underlines this by pointing out that no one before him has ever had a bird (or even an animal) named "Nevermore" sitting on a statue in his room. Pretty tough to argue with him there. We're pretty sure this bird-named-Nevermore thing is a joke, but we'll admit that maybe it's not laugh-out-loud funny. Lines 55-60 But the Raven, sitting lonely on the placid bust, spoke only That one word, as if his soul in that one word he did outpour. Nothing further then he uttered – not a feather then he fluttered – Till I scarcely more than muttered "Other friends have flown before – On the morrow he will leave me, as my hopes have flown before." Then the bird said "Nevermore." After that one word, the bird clams up and refuses to say any more (55). There's something mysterious and powerful about that word, though, and the speaker has the feeling that it contains the bird's whole soul (56). The bird keeps quiet, and the speaker, now maybe a little bit annoyed, slips back into his depressed mode. Now he sees the bird not as a welcome, amusing visitor, but just one more in the long line of friends who have abandoned him. So, he keeps talking to himself, reminding himself that, "Other friends have flown before" (58). He is sure that the bird will disappear by tomorrow, leaving him as alone and hopeless as ever (59). Then the bird gives him his favorite line again: "Nevermore." Lines 61-66 Startled at the stillness broken by reply so aptly spoken, "Doubtless," said I, "what it utters is its only stock and store Caught from some unhappy master whom unmerciful Disaster Followed fast and followed faster till his songs one burden bore – Till the dirges of his Hope that melancholy burden bore Of 'Never – nevermore.'" This time the answer is a little bit spookier. He said the bird was going to leave and the bird said, "Nevermore." That actually makes sense. It's "aptly spoken," as the speaker says. Again, he's a little freaked out, and again he looks for a plausible explanation. He tells himself that this bird only knows one word ("his only stock and store") and uses it for every situation. He even tells himself a little story about how the raven might have learned the word. He imagines that the bird had a really, really depressed former owner, whose life was such a mess that all he could say was "Nevermore." Lines 67-72 But the Raven still beguiling my sad fancy into smiling, Straight I wheeled a cushioned seat in front of bird, and bust and door; Then, upon the velvet sinking, I betook myself to linking Fancy unto fancy, thinking what this ominous bird of yore – What this grim, ungainly, ghastly, gaunt and ominous bird of yore Meant in croaking "Nevermore." For some reason he's still fascinated by the bird, and he repeats line 43, about how it beguiles his fancy. So he pulls up a chair, sits in front of the bird, and really lets his imagination go to work. He seems like an obsessive guy, and he's already pretty into this raven. He sinks into the chair and tries to think what this scary, ancient-looking bird could mean with this one word. Even though he guesses that it's just a random word the bird has learned, something still intrigues him; he can't quite let this go. Lines 73-78 This I sat engaged in guessing, but no syllable expressing To the fowl whose fiery eyes now burned into my bosom's core; This and more I sat divining, with my head at ease reclining On the cushion's velvet lining that the lamp-light gloated o'er, But whose velvet violet lining with the lamp-light gloating o'er, She shall press, ah, nevermore! He sits and thinks, and sits and thinks, in silence, "not one syllable expressing" (73). He imagines the "fiery eyes" of the bird burning through into his "bosom's core" (74). We think it's safe to say that our narrator is a melodramatic kind of guy. So he does some more thinking and guessing (or "divining" as he rather pompously calls it). Poe gives us some details of the room here and, as always, they are rich and luxurious (like the velvet cushion and a little scary (even the lamp-light seems to "gloat") (76). For some reason, the light and the cushion push him back to his old obsession. He remembers that Lenore will never sit on this cushion again (78), and that she's really gone forever. Lines 79-84 Then, methought, the air grew denser, perfumed from an unseen censer Swung by Seraphim whose foot-falls tinkled on the tufted floor. "Wretch," I cried, "thy God hath lent thee – by these angels he hath sent thee Respite – respite and nepenthe, from thy memories of Lenore; Quaff, oh quaff this kind nepenthe and forget this lost Lenore!" Quoth the Raven "Nevermore." Now things start to get a little weird. In his grief, our speaker imagines the air filling with perfume from an invisible censer (a globe that holds burning incense). To top that off, he imagines angels ("seraphim") swinging that censer. He even hears their footsteps on the carpet (80). Now that he's gone around the bend, he starts to yell at himself, calling himself a "wretch." He tells himself that this imaginary perfume thickening the air was sent from God to help him forget Lenore. He compares this perfume to nepenthe, a mythological drink that was supposed to comfort grieving people. He tells himself to "quaff" (that just means drink) this potion and forget Lenore. Just as we start to really wonder what he's raving about, the raven cuts him off by saying "Nevermore" (84). Lines 85-90 "Prophet!" said I, "thing of evil! – prophet still, if bird or devil! – Whether Tempter sent, or whether tempest tossed thee here ashore, Desolate yet all undaunted, on this desert land enchanted – On this home by Horror haunted – tell me truly, I implore – Is there – is there balm in Gilead? – tell me – tell me, I implore!" Quoth the Raven "Nevermore." Now the speaker starts to get seriously worked up and starts full-out yelling at the bird, calling him a "Prophet" and a "thing of evil" (85). Well, actually he backs off on the evil thing a little, moving back and forth between assuming that this bird has come straight from Satan (the "Tempter") or that it has just been blown in at random by a storm (86). The next line emphasizes the strangeness of the bird, who is all alone, but seems unshaken ("desolate yet all undaunted"). It also reminds us of how completely miserable our speaker is, stuck in a "desert land enchanted" alone in a "home by Horror haunted" (88). All he really wants is a little bit of hope, some possibility of comfort. So he asks the bird a typically pompous, bookwormish question: "Is there balm in Gilead?" (89) It's a Biblical reference, basically meaning, is there hope in my future, a possibility of comfort, peace, etc? Predictably, the bird shoots him down with "Nevermore." Lines 91-96 "Prophet!" said I, "thing of evil – prophet still, if bird or devil! By that Heaven that bends above us – by that God we both adore – Tell this soul with sorrow laden if, within the distant Aidenn, It shall clasp a sainted maiden whom the angels name Lenore – Clasp a rare and radiant maiden whom the angels name Lenore." Quoth the Raven "Nevermore." Our speaker seems to be pretty slow to catch on, or maybe he's starting to enjoy the torture the bird is inflicting on him. In any case, he keeps pumping this dry well, asking the bird another question, this one a little more to the point. He asks, in the name of God, if he will one day get to embrace his beloved Lenore again, in "the distant Aidenn" (i.e., Eden, or Heaven). The bird says, of course, "Nevermore." Lines 97-102 "Be that word our sign in parting, bird or fiend!" I shrieked, upstarting – "Get thee back into the tempest and the Night's Plutonian shore! Leave no black plume as a token of that lie thy soul hath spoken! Leave my loneliness unbroken! – quit the bust above my door! Take thy beak from out my heart, and take thy form from off my door!" Quoth the Raven "Nevermore." Finally, he completely loses it. That last "Nevermore" is the final straw, and he jumps up and tells the bird to get lost (97). He directs it to get back to the storm and the evil night it came from (98). He tells it not to leave any trace, not even a feather ("black plume"), and to take its lies elsewhere and leave him to his loneliness. He tells the raven to get off the statue, to take his beak out of his heart, and, basically, to go to hell. To which the Raven says, "Nevermore." This bird is here to stay. Lines 102-108 And the Raven, never flitting, still is sitting, still is sitting On the pallid bust of Pallas just above my chamber door; And his eyes have all the seeming of a demon's that is dreaming, And the lamp-light o'er him streaming throws his shadow on the floor; And my soul from out that shadow that lies floating on the floor Shall be lifted – nevermore! All of a sudden, we switch to the present tense. This isn't a story from the past, it's right now, and the raven is still there. He has turned into a kind of statue himself, a glowing, scary demon statue, whose shadow is cast across the floor. That shadow has trapped the speaker, imprisoned his soul. We start out hearing a story about a talking raven on a dark night, and we end up watching a man descend into his own personal hell. The Raven Symbolism, Imagery & Wordplay There’s more to a poem than meets the eye. Lenore This particular lady is the main focus of the speaker's obsessive thoughts. He brings her up constantly, and even when he tries to think about something else, he always ends up back at Lenore. Despite this, we don't actually learn that much about her. We don't hear what she looks like or how she is related to our speaker (wife? girlfriend? sister?). She's an idea, a memory, but she never really becomes a full-fledged character The Raven So this is a big one too. Not only is it the title of the poem, but even once we've heard all about Lenore, and the guy in his chamber, it's probably the image of the Raven that sticks most in our minds. It was a pretty great choice on Poe's part, a bird that looks like a part of the black night it came out of, a little scary looking, but also hard to read. The Raven is everywhere in this poem, but we'll hit a few key moments here. Night's Plutonian Shore This is the kind of big, spooky, complicated image that Poe just loves. It sounds spiffy and poetic, and it also manages to ball a bunch of mysterious images into one phrase. The phrase has three words, and also three parts: The Night. Darkness and night are both major symbols in this poem. They both represent the mysterious, maybe dangerous and scary power of nature. In addition, they just make for a cool atmosphere for a poem – it definitely couldn't take place on a sunny afternoon. Plutonian. This is an allusion to the Roman god of the underworld. The adjective "Plutonian" is meant to make us think of all the scary things that one associates with the underworld: darkness, death, the afterlife etc. Shore is a little more mysterious. It may be a metaphor that helps us to see the night as a vast ocean, washing up against the edge of this chamber. In a way, then, all these words help emphasize the ideas of darkness and night. Not just a dreary night, but also a vast ocean of hellish darkness. Very much Poe's style. Nepenthe This is an allusion to a mythological drug that you might take to forget your grief. From what we can tell, we think our narrator might really need some of this stuff. Speaker Point of View Who is the speaker, can she or he read minds, and, more importantly, can we trust her or him? So, we know this poem was written over 150 years ago, and we're sure that people talked differently back then. Still, we're not sure you would have met a lot of people in 1845 who walked around shouting things like: "Quaff, oh quaff this kind nepenthe!" (line 83). Our speaker is definitely the melodramatic type. He starts out at an emotional level of about nine on a ten-point scale; he then heads right through the roof to about fifteen. His tone is intense, almost frantic. He seems super-focused one moment, and then a bit spaced-out the next. Now granted, he's had a tough night, but from the sound of his voice and the choice of his words, we get the sense that he's wound pretty tight even when he's not talking to birds. We don't mean to make fun of him, just to point out that he seems to live pretty close to the edge. In fact, it's his intensity that makes him so captivating. Like a mad scientist on the edge of a discovery, his tone is pretty exciting. He makes the events of his life as electrifying for us as they are for him. The Raven Setting Where It All Goes Down The Library in Your Rich Uncle's Mansion So, we aren't lucky enough to have a rich, eccentric, childless uncle. But if we did, we bet he'd hang out in a room like the one Poe describes in this poem. We bet the curtains would be "silken" and "purple" (line 13). We bet the cushions on the chairs would have velvet violet lining" (line 77). The room in this poem feels like the perfect place to brood and mutter to yourself, especially if you don't have to work and can spend all your time thinking gloomy thoughts. Poe doesn't say what exactly this room is, but we imagine it being a library, shelves piled high with musty old books. There's probably a pipe and a bottle of brandy on the side table. We can see the spooky light from the lanterns playing over the scene, making everything seem even stranger and more exciting Sound Check Read this poem aloud. What do you hear? We think this poem sounds exactly like a magic spell. If you wanted to curse someone, or summon an evil spirit, we bet you'd want something that sounded exactly like this poem. Do you feel the way the rhythm pushes you forward, the way it starts to sound almost like a drum beat? For us, that rhythm even becomes a little hypnotic. Throw in all the repetitive rhyming and the poem sounds even more like some kind of incantation. It picks up speed too, starting out slow and quiet, and then building, getting faster and more intense until you can almost imagine someone yelling it. Check out lines 63-64: "Caught from some unhappy master whom unmerciful disaster/ Followed fast and followed faster till his songs one burden bore." Just try to read that slowly and calmly, without getting caught up and swept along by the wild, frantic sound of the poem. That's the great thing about the sound of "The Raven." Even as the events of the poem grow more intense, the words and the rhythm of the poem pick up too. By the end it almost sounds like a fist pounding on a table: "Take thy beak from out my heart, and thy form from off my door!" – Boom, boom, boom. The spell that Poe is weaving over us comes to a wild peak, and then disappears suddenly. What’s Up With the Title? Well, in one sense, the title is pretty basic. Since the poem is about a raven, "The Raven" makes a good title, as far as we're concerned. Still, Poe had other options. He could easily have called it "Nevermore" or "Lenore." Calling it "The Raven" does at least a couple of things. On the first reading, it prepares us for what is coming and gives us a little hint about the big event in this poem. After all, the Raven doesn't show up for a while, so we spend the first 38 lines wondering what the title refers to. More importantly though, the title focuses our attention completely on the bird. There are other things happening in this poem, but the title puts the raven at the head of the pack (or of the flock, if you will). It gives us one more reason to wonder what this bird is, where it comes from, and what it might represent. What is the poet’s signature style? Spooky sounds, even spookier themes, and lots of fun rhymes. When the poem you are reading features death (especially deceased women), an elaborate rhyme, and mournful language, you can be pretty sure you're dealing with Poe. He loved to tell stories about depressed men, many of them pining for the women who have abandoned them by dying. Poe was also very, very meticulous about arranging his poems for a certain effect on the reader. This effect was usually depression. Starting to notice a theme here? In particular, Poe felt that certain words could have an emotive effect on you: they would call up a particular set of feelings. One of the words used in this poem is "Nevermore." It's filled with longing and despair, a sense that nothing will get better, no matter how badly you – the reader – want it to. Combine the feeling of being completely depressed with hypnotic rhythm and rhyme, and you've got the essence of Poe. The Raven Trivia Brain Snacks: Tasty Tidbits of Knowledge In 1835 Poe married his cousin, Virginia Clemm. At the time, she was 13 years old! Every year, on Poe's birthday, a mysterious visitor (called the "Poe Toaster") comes to Poe's grave and leaves a half-full bottle of cognac and three red roses. Yes, Poe was a serious alcoholic. As for the roses, who knows? The cause of Poe's death is a famous mystery. Some say it was alcohol, others say rabies, some even say poison. Apparently it was also possibly a brain tumor, but that seems less exciting and Poe-ish to us. The Raven Allusions & Cultural References Literature, Philosophy, and Mythology Pallas (41, 104): This is a reference to the Greek goddess Athena, often called Pallas Athena, or just simply Pallas. She is primarily associated with wisdom, which makes her head an ironic place for the Raven to sit, since we can never quite tell if the bird is actually wise or is just saying the only word it knows. Since she's a goddess, though, she's also a symbol of the ideal woman, perfectly beautiful wise, virtuous, and strong. For a man who spends all his time thinking about the perfect maiden he has lost (Lenore), a bust of Pallas seems like a pretty good choice. Balm in Gilead (89): This refers to a biblical quote, from Jeremiah 8:22 "Is there no balm in Gilead; is there no physician there?" In a general sense this famous balm (a kind of healing ointment) has come to represent hope, peace, an end to pain. Obviously, since the origin is Biblical, there's an aspect of the peace of Christian salvation, although we can't quite tell how much the speaker of the poem believes in that. The Raven Themes Madness The speaker of "The Raven" sounds like he's had a rough life, and most people would probably be a little shaken up to find themselves talking to a bird. Still, we think it's entirely possible that he's insane, or at least pretty far down that road. He talks a lot about wild dreams, imaginary perfume, his burning soul, etc. Of course, the possibility that he's headed around the bend raises some other questions. Is this bird really talking? Is there a bird at all? Is this just a kind of fever-dream? We'll hold off on those questions for now, but keep them in mind. Theme of Love The speaker in "The Raven" loves a woman named Lenore. That's part of the nice balance of this poem. At times it's almost campy and over-the-top, with all the elaborate rhyming and fancy vocabulary. At its heart though, the poem is about a man who only wants one thing in the world: to be back with the woman he loves. Sadly, that's the one thing he absolutely can't have. This is a pretty depressing look at love; and, while Poe never even uses the word directly, love still pervades this poem. Theme of Man and the Natural World Many of the scary things our speaker faces on this crazy night have to do with the natural world. He imagines hostile natural forces all around him, surrounding his peaceful, civilized room, just waiting to break in. The dark night, the sound of the wind…they are all threatening and unfathomable. Then nature does break in, in the form of that arrogant, talkative bird. This is the big central confrontation of the poem, and it brings the idea of a conflict between man and nature right to the front. Theme of The Supernatural Once you've read "The Raven" through, you're probably pretty used to the idea of a talking bird. But step back from that for a second, and think about it. If we heard a bird talk, we'd probably run screaming from the room. At the very least, we think it qualifies as pretty darn supernatural. The speaker thinks a lot about where this bird came from, whether it's some kind of demon, or maybe even a prophet. He also ponders deep issues, such as the afterlife and the existence of God. Questions About Madness 1. Do you think the speaker is insane? We know we've suggested this possibility, but do you see it in the poem? Where? Is there another explanation for his behavior? 2. Is there a growing sense of insanity as this poem builds to its climax? What might give you that idea? 3. Does this poem make you feel a little crazy? 4. Is it possible that the speaker is making up or imagining some of the weird events in this poem? Questions About Love 1. Where does one draw the line between love and obsession? Can they exist at the same time? How would you describe the speaker's feelings for Lenore? 2. Do you find his love for Lenore touching? Or maybe a little cheesy? 3. Is there any way to know who exactly Lenore was, or what her relationship with the speaker was like? A wife, a girlfriend, a relative, just someone he knew? 4. Do you see any point where in this poem where love is not tainted by grief? Questions About Man and the Natural World 1. Do you think the Raven pushes our speaker over the edge, or does he do it to himself? Is nature torturing him, or his own mind? 2. Why do you think a raven was for Poe a useful symbol? What if, instead, the ghost of Lenore had showed up? 3. How does Poe represent the spooky side of nature? Why is that so important for this poem? 4. Is there anything really scary about the natural world in this poem, or does the speaker create all the terror in his mind? Questions About the Supernatural 1. Do you think religion plays an important role in this poem? If so, where do you see the evidence? 2. The speaker half-suspects the Raven is an evil spirit. Does this seem reasonable to you? What evidence can you muster for or against this theory? 3. Does the talking Raven actually seem supernatural to you? Is it possible that there is nothing going on here that can't be explained in a scientific manner? 4. Does it seem like the idea of heaven provides any lasting hope in this poem?