Food Prices, Ethanol, and Crude Oil

advertisement

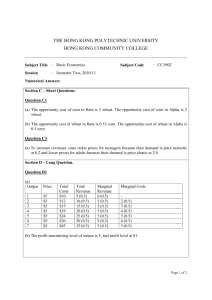

Food System All of the processes, people, materials, and infrastructure involved in producing the food we consume each day, including the required inputs and outputs for each stage in the food production process. These stages include: Growing Harvesting Storing Transporting Changing (Transforming or Processing) Packaging Marketing Retailing Preparing Consuming Convention or Industrial Food Systems •Rely on large-scale farming •Require massive farm inputs including fertilizers, fossil fuels, and machinery •Dependent on large-scale government subsidies •Technology dependent: processing, packing, GMO’s, etc. •Generate huge amounts of waste Alternative or Sustainable Food Systems •Encourage small to mid-size farms, but not necessarily opposed to high-intensity or large-scale operations •Require organic inputs: compost, manure, saved seeds, etc. •Not dependent on subsidies (wouldn’t it be nice, though, if the government subsidized broccoli and kale?) •Benefits from new technologies but can produce high-quality food using many primitive methods •Generates little to no waste Supermarket History First grocery store chains appear in the late 1900’s The Great Atlantic and Pacific Tea Company (A&P)---1859 Piggly Wiggly --- 1916—introduces self service grocery Safeway—1911 (Sam Sellig stores)— 1925 “Safeway” name Kroger--1883 First Supermarkets appear in the 1930’s First “true” supermarket may be King Kullen in Queens, NYC in 1930 Features: self-service separate product departments discount pricing marketing volume selling Supermarket Success •Transcontinental railroad---1869 •Automobile---1885, mass production 1914 •The Great Depression—1929 •Petrochemical fertilizer—The Haber-Bosch process for “fixing” nitrogen—1913 •Food Policy—1973 Farm Bill—established modern system of grain subsidies Big Players Pepsi-Co---c. $45 billion total revenue Frito-Lay Tropicana Quaker Gatorade Lipton Dole—c.$ 7 billion General Mills---c. $15 billion Betty Crocker Pillsbury Yoplait Green Giant Cascadian Farm Muir Glen Nestle—c. $111 billion Digornio Zephyrhills Edy’s Tombstone Haagan-Daz Hot Pockets Kraft—c. $41 billion Nabisco Ritz Grey Poupon South Beach Food Policies •Food policies are common, often very complex, and nearly ubiquitous •They are frequently contradictory • Ex. Farmers want higher prices while consumers want lower prices •Scope of food policy includes tariffs, subsidies, research, technology, health, safety, the environment, transportation and many other areas World Food Crisis of 2008-2009 World food prices began to rise sharply in 2007. As a result, countries producing food took steps to limit rising prices by keep more food “at home.” This helped stabilize domestic prices. Keeping more food for domestic consumption means fewer food exports. This further increases the price of food for countries that import food. Some food importing countries lowered tariffs on food to help stabilize prices; but, by making food cheaper, demand for imported food went up, so the price of food began to rise in global markets. Lesson Learned from the Food Crisis of 2008/2009: When each country focuses only on itself, things can spiral out of control. or Westhoff’s “Rule of Thumb”: “Government policies can both raise and lower food prices. Some policies that try to make domestic food prices more stable can make food prices in other countries more volatile.” Example: If the U.S. requires the use of biofuels, the price of grain and vegetable oils rise in Asian markets. Why? Subsidies in High-Income Countries (esp. the United States) When the U.S. government subsidizes grain/legume production (wheat, corn, soy, etc.), the prices of these commodities remain “artificially” low. Farmers can charge less than the fair market price because the U.S. government makes up the difference. As a result, American consumers and American corporations can buy grain at a very low price. BUT, we can also export of grain at artificially low prices to the rest of the world. When we do this, farmers in other countries cannot compete with the low price of important American commodities. As a result, some farmers are forced into a cycle of poverty because they can’t make a profit on their crops. Subsidies: A Historical View Governments develop subsidies to cope with industrialization As more and more people make money in other sectors of the economy, outside of agriculture, farmers need more and more help to stay afloat and preserve their way of life. The U.S. began its subsidy programs in earnest in 1933 with the Agricultural Adjustmen Act under the New Deal At the time of the Great Depression, farmers needed help to survive. Most farms were small and most farmers were poor. Most farms today are large commercial farms that do not need subsidies to survive. Q: So Why Do We Still Have Subsidies? A: The Farm Lobby and the Farm Bill The “Iron Triangle” keeps the subsidy system in place: House and Senate Agricultural Committees USDA Farm lobbyists (The American Farm Bureau Federation and The National Farmers’ Union, National Corn Growers’ Association, U.S. Wheat Associates, The National Cotton Council, etc.) The Biofuel Conundrum On the one hand, promoting biofuels increases the prices of grains and seed oils around the world; On the other hand, government subsidies keep the prices of grains and seeds artificially low. Q: So, what’s the problem? Should these competing forces balance out? A: Sometimes, but not all the time. When demand is changing quickly, things can spiral out of control. Ethanol in the United States Three-pronged policy: 1. U.S. government subsidizes ethanol production Ex. Tax credit: If you blend ethanol with your regular gasoline, we will give you a credit on your taxes (i.e., lower your overall tax bill). This allows fuel companie to pay a high price for ethanol because it’s in their interest to use it. 2. We place a tariff on ethanol imports from Brazil and other countries 3. We mandate a minimum level of biofuel (ethanol) use: the Renewable Fuel Standard; Energy Independence and Security Act of 2007 Rice: An Example of How Policy Trumps Supply Looking at the chart on p. 63 in Westhoff, explain why people were, literally, starving for lack of food in 2008, even though world stocks of rice increased during the course of the year. Back to Biofuels in the U.S. If the U.S. eliminates all policy supports for ethanol production, what will happen? One scenario: Demand for ethanol would decrease sharply Demand for corn would decrease Corn price would fall Farmers would plant more soybeans and wheat since corn is less profitable Soybean and wheat prices would also fall Food prices would fall Meat prices would fall and meat production would increase What about other countries who depend on U.S. exports? Food Prices, Ethanol, and Crude Oil If oil prices rise, the demand for ethanol increases Combined with the ethanol tax credit (a subsidy), this would keep ethanol prices relatively high Corn demand increases Food prices increase Food Prices, Ethanol, and Crude Oil If oil prices fall, demand for ethanol decreases Even with the ethanol tax credit (a subsidy), ethanol prices in late 2008 fell considerably Corn demand decreased Food prices decreased The Renewable Fuel Standard (RFS) became “binding,” establishing a “floor” for minimum levels of biofuel use—so the price of biofuels was kept artificially high. Corn prices and food prices remained artificially high. A Closer Look at Tariffs Tariffs increase the price of food in the importing country and decrease the price of food in the exporting country. Ex. If we tax Brazilian sugar, our sugar prices go up, while Brazilian producers must lower their prices to remain competitive in the U.S. and world markets. Export subsidies: allow buyers in importing countries to obtain food at lower-than-market prices. Prices are artificially inflated in the exporting (subsidizing) country and artificially deflated in the importing country. Other Forms of Subsidy and Government Support Quotas Farm credit services Fuel and Fertilizer subsidies Food assistance programs, “Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program” in the U.S. (aka ‘food stamps’) Commodity stores (government stockpiles of grain) What about NAFTA? Is it good or bad? (Here we are again!) Food Regimes A term used to describe “the international food order” (Winders 132) The set of policies in place in countries all over the world that set relative prices of food and encourage specialization in food production Important features of food regimes: 1. “Set the market” and thus structures the production and distribution of agricultural commodities (and shapes the international division of labor of agricultural production) 2. Made possible through state regulation of food markets (tariffs, subsidies, etc.) 3. Control the direction of trade flows 4. Change throughout history More Characteristics of Food Regimes Characterized by play between free market supporters and those seeking more regulation (i.e, “protectionists”) The flow of basic good commodities, especially grain, help to define social, political, and economic relations on a global scale. Flood regimes create relationships of dependence in which some nations rely on others for their food supply. Usually dictated by a “hegemon” or power nation or group of nations that are able to dictate patterns of production, trade, and development (example, Britain in the 19th century, U.S. today) Food regimes play an integral role in establishing and/or threatening food security. Food Security Defined as the condition in which “all people at all times have access to sufficient, safe, nutritious food to maintain a healthy and active life.” (World Food Summit 1996) Includes “physical and economic access to food that meets people's dietary needs as well as their food preferences.” (WHO) Applies to nations, regions, cities, or even households Q: Why is it important to talk about food regimes and food security? A: Because there are a lot of problems involving food around the globe, and we don’t have solutions for them. Some tough binaries to consider: There isn’t enough food to feed everyone in the world. / There is enough food in the world to feed everyone adequately; the problem is distribution. Future food needs can be met by current levels of production. / We are running out of production capacity and the current system is unsustainable. National food security is paramount. / National food independence is not a logical goal because of global trade. Globalization and free trade movements lead to the persistence of food insecurity and poverty in rural communities. / Globalization helps the poor by lowering food costs and efficiently organizing production, distribution, and the division of labor. The U.S. Food Regime Emerged strongly after World War II Fundamentally protectionist •price regulation •purchasing surplus commodities •subsidies •production controls Most significant development was the flood of grain, particularly wheat, into the world food supply U.S. created markets for grain exports and also gave away surplus as “food aid” to impoverished or “developing” countries As U.S. grain became cheaper and more abundant, some nations experienced a collapse of agrarian sectors and “massive rural-to-urban migration” (Winders 136) The Problem with U.S. Food Policy after WWII Relied on a failed attempt to manage supply •Limited the number of acres on which farmers could produce commodity crops •Offered minimum price supports per bushel Combined, these two policies encourage farmers to grow as much as possible on the least amount of land This high-yield revolution was achieved by the invention of chemical fertilizers (the Haber-Bosch process of fixing nitrogen) By the mid 1950’s we were awash in a sea of wheat, cotton, and corn. While the livestock industry took up the extra surplus of corn, the wheat and corn suppliers were in trouble. As a result, the U.S. aim to control supply (production) had failed. We turned to the other side of the coin: consumption and export subsidies. The U.S. and Global Free Trade: GATT 1948—The U.S. used its global influence after WWII to pass GATT, the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade • established “most favored nation” trading status that extended trade preferences to all partners of the agreement • average import duties fell from 40% in 1940’s to 5% by 1989 • did not apply to agriculture! (GATT exempted agriculture from its restrictions on tariffs and subsides and allowed the U.S. and other countries to continue to control supplies/production) •The wheat and cotton lobbies opposed liberalization of agricultural markets in a historical turn around (see Winders 144). •As more and more countries signed on to GATT, they also adopted U.S. supply management practices in order to compete with cheap U.S. exports Food Aid: Charity or Greed? After WWII, the U.S. developed to policies to help reduce the surplus of food commodities, especially wheat Marshall Plan • helped to rebuild Europe while allows U.S. to unload surplus 1954----“PL 480” (Public Law 480) • U.S. sells grain to needy countries at “concessional” prices • Accounted for a whopping 80% of U.S. wheat exports by 1965 Q: Who benefited the most from this “aid”? FAIR Act The Federal Agricultural Improvement and Reform Act of 1996 *Ended supply management policies for U.S. wheat, corn, and soy, but not tobacco or peanuts *Ended federal requirements to leave a certain amount of land unplanted (aka the ARC, or Acreage Reduction Program) *Ended price supports, or minimum prices set by the government for individual commodities like wheat and corn. (If prices fell below these minimums, the government would make up the difference with cash payments to farmers). *Replaced price support payments with direct payments to farmers regardless of market prices (based on a % of total farm expenses and number of acres planted in the past) *Kept export subsidies in place Q: Why do most scholars argue that the FAIR Act was a victory for Republicans? Q: Why did Bill Clinton, a Democrat, sign the FAIR Act? •Corn •Livestock/Chicken •Rise of agribusiness, esp. Cargill and ADM •South shifting to the right Washington Consensus Neoliberalism Green Revolution