What it Means to Have a Sense of Wonder

advertisement

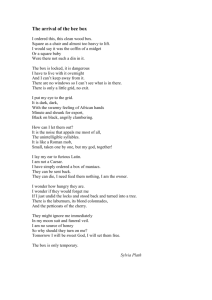

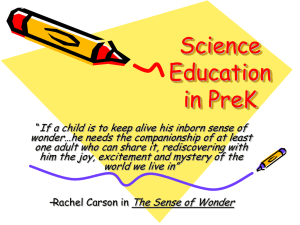

What it Means to have a Sense of Wonder and Why it Matters What it Means to have a Sense of Wonder and Why it Matters Gayle Bodge Ecological Perspectives of a Bioregion: Cobscook Bay Lesley University Chunn, Fessenden, O’Connell and Sprangers August 20, 2011 1 What it Means to have a Sense of Wonder and Why it Matters 3 The Beginning: Excerpts from my Graduate Application Essay I have been looking for a graduate program to deepen my own personal knowledge about the environment, but also how to best engage others in thinking about their relationship with the environment. * This program will push me to really engage with the work that I am doing, and want to do, to reflect upon myself as an environmental citizen and the choices that I make in my daily life, and to share my knowledge with others: my family, co-workers, students, and teachers. * I believe that education is how the world will change, as long as those educational experiences are meaningful. Skills, concepts, content, in other words “the standards” need context in students’ lives. Students need to understand “Why am I learning this? Why is this important to me?” They need to be personally invested in the issues or questions that they are exploring. * Throughout these experiences, students need to be given multiple opportunities to make meaning of the issues for themselves. They need to explore the issues from different angles, using different methods, taking on different roles, working within and outside of their comfort zones. Throughout the process students will not just discover answers to a question, but they will discover themselves as learners. * Students will be able to apply skills and concepts to real life situations as they make meaning of issues and answer questions. * I want to make a difference. I am passionate about education, about teachers, about students, about the environment. I want to engage people with their place, with environmental issues affecting where they live, and enable them to make decisions in their daily lives that will have a positive impact on their own environment. I want to influence people to be better environmental citizens, locally and globally. * This program will make me a better citizen, mom, educator…but aren’t those really all the same thing? *Denotes the end and/or beginning of each excerpt from my application essay. Introduction My biggest challenge coming to Cobscook Bay for the Ecological Perspectives of a Bioregion course was letting go of the everyday, to allow myself to be in the moment. I have a constant to do list that exists in my head. While I’m working on one thing, I’m also thinking about the next. Time outdoors just to sit, breathe, and be, doesn’t make it on the list. The time I do spend outdoors is with my children, trudging around the yard, picking flowers, building fairy houses, and digging in the garden. These were all experiences that filled my childhood, and are ones that I put What it Means to have a Sense of Wonder and Why it Matters 4 great value on and have played a big part in shaping who I am today. I still feel a sense of wonder for nature, and I enjoy watching my children express their own wonder. Although connecting with nature as a child is so important in shaping the adults you will become, I think that maintaining that connection as an adult is equally important. Parents, educators, other adults, institutions – the culture itself – may say one thing to children about nature’s gifts, but so many of our actions and messages – especially the ones we cannot hear ourselves deliver – are very different. And children hear very well. (Louv, 2008, p. 14) Our daily lives are so driven by structure, media, and technology, it is easy to let that connection to nature go. To ensure that my children, family, and the students and teachers I work with build and maintain a personal connection with nature, I need to do so as well. “I need to be the change I want to see.” (Mahatma Gandhi quote) The Sense of Wonder A child’s world is fresh and new and beautiful, full of wonder and excitement. It is our misfortune that for most of us that clear-eyed vision, that true instinct for what is beautiful and awe-inspiring, is dimmed and even lost before we reach adulthood. If I had influence with the good fairy who is supposed to preside over the christening of all children I should ask that her gift to each child in the world be a sense of wonder so indestructible that it would last throughout life, as an unfailing antidote against boredom and disenchantments of later years, the sterile preoccupation with things that are artificial, the alienation from the sources of our strength. If a child is to keep alive his inborn sense of wonder without any such gift from the fairies, he needs the companionship of at least one adult who can share it, rediscovering with him the joy, excitement and mystery of the world we live in. (Carson, 1956, pp. 42-43) What it Means to have a Sense of Wonder and Why it Matters 5 What is a Sense of Wonder The evening was humid, the grass was damp, and the sky was turning that purplish sort of gray it does when the sun sets behind the clouds. It was the perfect weather for slugs. Headed in to get ready for bed my son, aged 1, and daughter, aged 3, spied a slug. He was slowly making its way across a cement patio stone, leaving a trail of slime behind him. “Look at its antennae!”, my daughter said down on her hands and knees, meeting the slug at eye level. My son grunted. He reached out his pudgy hand and batted in the slug’s direction. The slug immediately curled up into a tight ball, my son squealed, so did my daughter! His next approach was gentler, and the slimy, wet, cool slug stuck to his finger. A deep belly laugh resulted. My daughter got close, about an inch before contact with the slug, she recoiled; maybe next time. We said our good nights and thank-yous to the slug, and headed in. I see a sense of wonder in my children. It is expressed through their insatiable curiosity and endless questions, their desire for exploration, adventure, and play, and their ability to observe and focus on things often overlooked. These qualities aren’t unique to them. During my time at Cobscook Bay with my Ecological Teaching and Learning class I shared in several occasions when a sense of wonder deepened someone’s experiences with nature. We were well over our rubber boots in the chilly waters of Cobscook Bay where Dr. Carl Merrill had set us loose in the intertidal zone. We were so enthralled by this mysterious world that can survive the extremes of cold salt water and the hot dry sun that we didn’t care much about the incoming tides. I found a green sea urchin hidden on a rock amongst the knotted wrack. Katie, who was beside me at What it Means to have a Sense of Wonder and Why it Matters 6 the time, had never seen one before. She held him in her hand and shouted to others, “Look, a sea urchin!”, like an excited child would. Katie spent enough time watching the urchin that he became comfortable in her hand and started to creep his way up her arm with his tube feet. “This is my species”, she said, referring to the Council of the Beings, the sea urchin had chosen her. (K. Anderson, personal communication, July 11, 2011) I was in the dining hall working on my journal when Margaret came running in, wide eyes and with a huge smile! “I get it! The Red-Eyed Vireo is a prophet!” she exclaimed. “I was running through the path and all I could hear was the call of the prophet bird, “Where are you? Here I am.” So I hollered back, “I am here! This is now!” On the first night of grad camp as we established norms, Margaret had shared with us that being present in the moment was important to her, and the Red-Eyed Vireo helped her to truly be present in that moment. (M. Burke, personal communication, July 24, 2011) Through a wonderful display of dance, story, and glow sticks, Ryan shared with us during the council of the beings the existence of bioluminescent plankton that lives in the waters of Cobscook Bay. On the last night of grad camp, I accompanied him for a night swim. I was on the waters edge with a flashlight. With the water at high tide, Ryan slowly made his way in, his excitement growing with each step and he could see the waters around his feet beginning to glow. Wading turned into full body submersion followed by splashes, jumping, and throwing water up in the air. “Do you see them?”, Ryan yelled, referring to the glowing plankton, unable to contain his excitement. “Yes! I do see them!” I replied, while What it Means to have a Sense of Wonder and Why it Matters 7 splashing at the shallow waters near my feet. (R. Mayeda, personal communication, July 27, 2011) A sense of wonder exists in us all. At one time having a sense of wonder was essential for our survival. Looking closely at the environment and discovering patterns allowed us to track animals, understand what habitats different plants grew in, and prepare for the change of seasons. Curiosity and exploration brought about new discoveries of places, food, people, and tools for survival. Today it is not apparent how we rely on our environment for survival. Today survival seems to depend upon the price of gas, sales at big box stores, and a good Wi-Fi connection. Today a sense of wonder is most apparent in people who grew up with nature, who live their lives with a connection to the land. What it Means to Have a Sense of Wonder A deep connection to the environment and sense of wonder can still be seen today in native cultures and traditions. You can hear it in their language, see it in their actions, and learn it through their stories. We were blessed to have the opportunity to spend a few days with Fredda Paul, a native Passamaquoddy medicine man, and his wife, Leslie Wood, a talented storyteller. Fredda shared with us many stories about growing up and learning native traditions, stories, and medicines from his grandmother. “Pay attention and you will learn. If you want to be taught, listen.”, was something she commonly said to him. She instilled in Fredda a deep respect and connection to the land through native tradition and culture. What it Means to have a Sense of Wonder and Why it Matters 8 The stories she shared with him, and he with us, demonstrated the wonder and respect native peoples have for plants, animals, land, and water. Everything held powers greater than what most people could see. The eagle carried prayers to the creator, many plants had medicinal properties, and the ocean, or supeq, was holy water. When you swim in salt water at high tide or right after, as the tide goes down, it carries your impurities away. Their respect for the land, for native culture and tradition, and sense of wonder has led Fredda and Leslie to share their passion, knowledge, and talents with others. They have made traditional native medicines and collecting native oral histories their lives’ work. Their wonder, belief, and respect in what they do has healed people and has contributed to keeping alive native traditions and stories by sharing them with younger generations. I’m excited to share these stories with my children and explore our own backyard, wondering what medicinal powers are back there. If we want to truly return to the land, then native traditions can guide us there. (F. Paul and L. Wood, personal communications, July 12 – 13, 2011) In 1765, a member of the Passamaquoddy tribe guided Robert Bell, an immigrant from Scotland, to a river where the fresh water meets the salt. Here, on the shore of Cobscook Bay, Robert started a grist-stone mill using the power of the tides. Today, in its ninth generation, Tide Mill Farms is still in operation by the Bell family. Aaron Bell (8th generation) and his wife, Carly DelSignore share a value for local organic food. They found that it was difficult to find access to the food they desired. Not willing to give up on their values, they began growing and selling organic vegetables, meat, and milk. Through their passion and perseverance, they What it Means to have a Sense of Wonder and Why it Matters 9 are able to provide local organic food to their family and community. (A. Bell and J. Bell, personal communication, July 10, 2011) Their goals for the farm include connecting people to healthy food; educating consumers and their community about the importance of locally farmed, organic food; strengthening their local economy; and rejuvenating agriculture as an economically viable lifestyle in the remote Washington County. The Bell family hopes to leave behind a more enriched environment for the future generations. (http://www.tidemillorganicfarm.com/ourStory.htm) Last summer my father-in-law started a small family farm; laying hens, meat birds, pigs, goats, rabbits, and a vegetable garden. I hadn’t thought much about how meaningful these experiences will be for my kids, my family, growing up knowing where our food comes from, and having a relationship with our food and the land until meeting the Bell family. They view their farm as a schoolyard for their children and integrated into the busy daily farm life for this family are learning experiences for their children. From an early age they learn respect for the land, for plants, for animals, and are given opportunities to explore, grow, and express their sense of wonder. “Everyone wants to be a farmer. Deep down inside, everyone wants to be a farmer”, shared Aaron. (A. Bell, personal communication, July 14, 2011) Being a coastal state, fishing is also an important resource to Maine. Lobstering started in earnest in the 1700’s, and is a big component of coastal Maine culture, supporting families for generations. Jeremy Cates grew up in Cutler, Maine, as did his father, grandfather, and great-grandfather. This 4th generation lobstering What it Means to have a Sense of Wonder and Why it Matters 10 family has experienced the lobster industry grow and evolve in Maine to become the sustainable fishery it is today. Jeremy could have started his lobstering career after graduating high school, but his passion for the sea carried him through his college education, where he gained a greater understanding of lobsters and their role in the Gulf of Maine ecosystem. Jeremy, like many other lobstermen in Maine, has a desire to keep lobster populations, and in turn the lobstering industry, healthy for generations to come through pro-active management practices. He lobbies to maintain these restrictions, believes in them, and sees the results through his lobstering business. Growing up in a lobstering family instills great respect for the ocean, the power of the seas and the life beneath its surface. Jeremy describes his learning experiences and those he desires for his children as, “School is what you make it. It can be anywhere you want it to be.” His experiences growing up, learning on a lobster boat, nurturing his sense of wonder, and continuing to do this today through his lobstering business and his children are evident in his passion when he shares stories from his work, his family, and his life on the sea. (J. Cates, personal communication, July 15, 2011) Growing up with a sense of wonder, with a respect for and knowledge of the land builds deep connections in a child. These connections become evident in adults through the values, actions, and choices they make. Because of their connections to nature, Fredda and Leslie, the Bells, and Jeremy contribute to our survival, through food, medicine, and sharing their passion for nature. What it Means to have a Sense of Wonder and Why it Matters 11 Why it Matters to Have a Sense of Wonder In the space of a century, the American experience of nature – culturally influential around the world – has gone from direct utilitarian to romantic attachment to electronic detachment. (Louv, 2008, p. 16) What if Aaron Bell didn’t grow up on a farm, or Jeremy Cates on a lobster boat, or Fredda Paul without the teachings of his grandmother? What if a child wasn’t given the opportunity to explore the outdoors, learn a respect for the environment, and see these qualities modeled by an adult? What if a child grew up without making memories that connect them to nature? What if they only experienced prescribed play in structured settings with boundaries designed by others? How would this impact these children as adults? I believe that all of us are born with an innate sense of wonder, with deep curiosity, a desire to explore, and an eye for the often unseen, with skills that make us natural learners. It isn’t often that these qualities are expressed in our daily lives as adults and influence the decisions we make and are shared with others. Somewhere, somehow in our experiences growing up, these qualities diminish, or grow dormant. Where do these qualities go? What happens to them? Do kids grow out of these qualities? Can they grow back into them? Or are they taught out of us? By schools, by parents, or by both? Does our culture’s view on what education is, or should be, restrict or limit children from being the natural learners they were born to be? Do we teach kids to forget how to learn? A traditional view and the current structure of schools, of public education is knowledge transfer. Schools have not been designed to offer students experiences, What it Means to have a Sense of Wonder and Why it Matters 12 to give students the opportunity to explore, discover, and make personal meaning, to truly learn. You can know lots of facts, but unless that knowledge is meaningful to you, it won’t influence the values, actions, and decisions you make in your life. We cannot protect something we do not love, we cannot love what we do not know, and we cannot know what we do not see. Or hear. Or sense. (Louv, 2011, p. 104) The goal of education, teachers, and parents should be re-instilling or nurturing the natural learning qualities, a sense of wonder in children. Teachers should play the role of facilitators or mentors and help kids recognize and develop their skills, by presenting them with new experiences and challenges, and by providing the tools and resources to aid them in their own natural learning and the discovery of self and the world around them. So how do you create an environment that not only allows and accepts these things, but also expects them, and fosters them? Change is hard. Implementing lasting change in schools can feel like turning around an ocean liner. Stopping the ship takes a long, long time. Then you need more time to turn it around and yet more time to develop momentum to go in the new direction. And then, if you don’t remember to turn off the autopilot, the ship will return to its old course. (Evans, 2005, p. 251) But change is necessary. The current education system is driven by standards and assessments, the outcomes of which determine the funding a school will receive. The design of this current system has created classrooms dominated by knowledge transfer, with teachers who are pressured into teaching to the test. Despite this current system, change is possible. What it Means to have a Sense of Wonder and Why it Matters 13 Interdisciplinary communication works only if there is a real problem to be solved, and if the representatives from the various disciplines are more committed to solving the problem than to being academically correct. They will have to go into learning mode. They will have to admit ignorance and be willing to be taught, by each other and by the system. It can be done. It’s very exciting when it happens. (Meadows, 2008, p. 183) Currently many states, including Maine, have taken on the challenge of developing an Environmental Literacy Plan for k-12 schools, with the goal of creating an environmentally literate citizenry. If the No Child Left Inside Act is included in the reenactment of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act, then significant funds will be available to states with Environmental Literacy Plans already in place. (http://www.maine.gov/education/lres/scitech/documents/eco_lit_brochure_V56-10.pdf) Change is possible. My Sense of Wonder If I was told at the beginning of my experience at Cobscook Bay that I would come to understand, appreciate, and long for a sit-spot experience, I wouldn’t have believed it. I have spent many nights rocking my beautiful babies, and instead of staring at them, marveling at the miracles they are, I compose emails in my head, answer ongoing questions from work, run through and add to my to do list to make sure my house and family are in order. I can’t seem to turn my brain off. But here, in Cobscook Bay, taken out of my everyday life I have finally found my ability to just be. I didn’t need to be anywhere else. I could just be here. It started with 10 minutes of group silence in a magical mossy spot along the Moosehorn National Wildlife Refuge trail, became an hour at a beautiful cobble What it Means to have a Sense of Wonder and Why it Matters 14 beach with frigid waters along the Quoddy Head State Park coastal trail, and it built up to four hours sitting along the banks of Cobscook Bay looking over reversing falls, watching and listening the tide quickly encroach upon my (not-so) stellar sitspot. I found myself finally able to clear my mind. To just be, to observe and explore my surroundings, to experience them with all my senses, and to give my quiet mind permission to reflect, make connections, and have deep thoughts about this place, about life, about being. Sit. Close your eyes and listen. Do you hear the wind rush past your ears? The waves crashing on the rocks, The water trickling as it recedes. Do you hear the birds calling from the trees behind you? Sit. Close your eyes and smell. Breathe in deeply the sweet salty breeze. Do you feel it fill your lungs with life? Sit. Close your eyes and feel. Embrace the chilly wind as it gives you goose bumps, Rejoice in the sunshine as it gives you warmth. Do you feel the roughness of the rock beneath you, aged and weathered over time? Sit. Open your eyes and look. Look out over the ocean that connects us all, That brings us life, That feeds our soul. Do you see the mystery and beauty of it all? Sit. And be here. (written by me during a sit-spot along the Cutler Coast) I want to play a role in nurturing or re-instilling a child’s sense of wonder. I want to play a role in changing our culture’s views on what education should be. I What it Means to have a Sense of Wonder and Why it Matters 15 want my children to keep growing and learning and being the curious, thoughtful, inquisitive, excited, and appreciative people they are. My sense of wonder for nature, particularly the marine environment led me to pursue a Marine Science degree. My experiences sharing my passion for the marine environment with others has led me to pursue science education. Science is all about asking questions, making observations, collecting data, drawing conclusions, and sharing your findings. To me, I think it is pretty similar to having a sense of wonder; both involve being curious, looking closely, and exploring. But I feel that there is something missing in science, something that having a sense of wonder can provide. Science is based on processes, evidence, and facts. Making personal connections, finding meaning, and gaining appreciation for our natural world and how it works; developing a sense of self-awareness, and respect and responsibility for our environment are not a part of doing science. They may be a side effect, but there isn’t a part of the scientific method that focuses on these aspects, develops them, or nurtures them. Reading Clifford E. Knapp’s article, The “I-Thou” Relationship, Place-Based Education, and Aldo Leopold, gave me a sense and hope for how combining placebased education and science can help to create and nurture a sense of wonder. I find that the components of science inquiry (http://www.nsf.gov/pubs/2000/nsf99148/htmstart.htm) and place-based education (Knapp, 2005, pp. 279-280) align, and that place-based education provides a context for science inquiry. And throughout both of these approaches are What it Means to have a Sense of Wonder and Why it Matters included key elements of a sense of wonder; curiosity, questioning, observations, discovery, and personal learning (as shown in Figure 1). Figure 1: Visualization of the alignment of the processes of Scientific Inquiry, Place-Based Education, and the role of a Sense of Wonder 16 What it Means to have a Sense of Wonder and Why it Matters 17 My current work involves creating curriculum resources for teachers that are driven by scientific inquiry, and are developed around place-based issues. Now that I see how these processes better align, and involve the qualities of a sense of wonder, I will develop resources that create opportunities for students and teachers to nurture and develop their sense of wonder. I’ll also provide teachers with solid experiences, examples, and resources that tie together the need for, and the meaning of having a sense of wonder. There are few professions in which being a truly great human being and embodying the best qualities of humanity (compassion, wisdom, kindness, curiosity, generosity, courage, perseverance and so on) is part of the job description, but teaching is one of them. (http://humaneconnectionblog.blogspot.com/2011/08/what-teachers-arethemselves.html) Nurture a sense of wonder in yourself, encourage it in your children, and share it with others. Ground yourself and your children in your place with an appreciation and deep respect for nature, community, and family and then send them off with hope, possibilities, and dreams. In the words of Jane Bell, “The greatest gift you can give your children is boots and wings.” What it Means to have a Sense of Wonder and Why it Matters 18 References: Carson, R. (1956). A Sense of Wonder. New York, NY: Harper & Row. Evans, A. (2005). Changing Schools: A Systems View. In M. K. Stone & Z. Barlow (Eds.), Ecological Literacy, Educating our Children for a Sustainable World (pp250-257). San Francisco, CA: Sierra Club Books. Knapp, C. E. (2005). The “I – Thou” Relationship, Place-Based Education, and Aldo Leopold. Journal of Experiential Education, 27(3), 277-285. Louv, R. (2008). Last Child in the Woods. Chapel Hill, NC: Algonquin Books. Louv, R. (2011). The Nature Principle. Chapel Hill, NC: Algonquin Books . Meadows, D. H. (2008). Thinking in Systems. White River Junction, VT: Chelsea Green Publishing Company. National Science Foundation. (2000). Foundations Vol. 2 - Inquiry: Thoughts, Views, And Strategies for the K-5 Classroom. Retrieved from http://www.nsf.gov/pubs/2000/nsf99148/htmstart.htm