MULTICULTURAL TEAMING 0901

MULTICULTURAL TEAMING

Objective:

The objective of this session is to examine some of the factors in effective teamwork when team members are drawn from varying cultural backgrounds. The session will address the importance of sensitivity to SEND’s multicultural nature and increasing internationalization, dimensions of cultural values that distinguish different ethnic peoples with a view to understanding the impact of cultural differences on relationships in a ministry team, and fundamental principles for effective multicultural teaming in the various contexts of SEND International.

Outcomes:

Following this session, participants will be able to:

Express the significance of the corporate SEND value of “unity in diversity” for mission relationships;

Explain five dimensions of cultural values and their impact on relationships and team ministry;

Identify their personal cultural value profile and reflect on the points of comparison or contrast with their target culture and potential team cultures;

Explain the basic model of team formation and five key dysfunctional patterns to be avoided in team ministry.

Focus:

How culture impacts everyday team and ministry interaction

Communicating in a multicultural work situation and avoiding misunderstandings

Managing conflicts by understanding the causes and types of conflicts

Impact of culture on leader-member relationships, time management, decision-making

Outline:

Introduction

I. Unity in Diversity – A SEND Value

II. Multiculturalism – Defined and Illustrated

III. Cultural Dimensions in Contrast

IV. Principles of Effective Multicultural Teaming

Conclusion

Introduction

“Culture is more often a source of conflict than of synergy. Cultural differences are a nuisance

at best and often a disaster.” (Geert Hofstede, Emeritus Professor, Maastricht University)

This quote sums up what many of us feel when we find ourselves trying to relate to people of a different cultural background, learn to understand them and their idiosyncratic responses, and attempting to function with them in ministry effectively and smoothly. We hope in this session to look at the reality of cultural diversity in SEND and understand some of the dynamics that make different people respond in varying ways as they relate in teams together, grasp several key principles for effective team ministry in a multicultural team, and then go out to be better team players in the growing cultural mosaic of SEND.

Multicultural Teaming

I. Unity in Diversity – A SEND Value

SEND International holds to a central corporate value of “unity in diversity”:

“We incorporate missionaries of many nationalities in the task of discipling the nations. Our desire is to have a multinational membership working together in harmony towards the fulfillment of the

Great Commission.”

This commitment is intentional (“we incorporate those of many nationalities. . . our desire is to have a multinational membership. . .”). We are pressing forward in a process of internationalization as a mission. We now have about 10% non-North American membership, judging by sending country, but the ethnic diversity within the mission is really more pronounced than this proportion suggests. We value having those of differing backgrounds working together, and each member of SEND should reflect on his or her commitment to this reality.

The goal is harmony out of the mix of cultures and nationalities among the members of SEND.

II. Multiculturalism – Defined and Illustrated

A. The Reality of Multicultural Teams

We arrived for our first church planting work knowing two of the other “units” that we would be working with. One was a couple from Germany with children about the ages of ours. The other was a

Chinese-American woman who had the language and was strongly gifted. As we began to function as a team, it was apparent that our expectations, gifts, and even personalities were very different. We needed to invest significant time in seeking to understand one another, and to come to joint decisions in the ministry of the team. And yet we felt that we needed to model the unity that Christ gives through our diverse backgrounds as His body, even as we planted the church. We had the opportunity to demonstrate that our unity in Christ superseded the cultural differences we brought to the team. Others will have to judge how well we managed in the effort!

B. The Biblical Ideal

Scripture indicates that God has designed for cultural and ethnic diversity in the church, the Body of

Christ, and that this distinctive will endure even in our glorified state (Rev. 5:9, 7:9). The Word of

God also teaches that divisive consequences of ethnic and cultural differences are clearly done away in Christ, so that the church should not be a Body divided by race and ethnicity (I Cor. 12:12-13; Col.

3:11). Thus, we are presented in Scripture with the ideal of an essential unity within a Body that is diverse in its cultural and ethnic expression.

C. Managing Expectations

It is important to anticipate that you will be facing not only a new culture of the people to whom

God is sending you to serve and proclaim Christ, but you also are facing cultural distinctives of those with whom you will be serving, your fellow members of SEND. And often these are the more difficult relationships to accept and grow into harmony with in the work. Expectations are important here, so that you can prepare to meet the reality of the diversity of your team or coworkers.

D. Key “Flashpoints” in Team Relationships

Communication

Decision-making

Conflict resolution

2

Multicultural Teaming

III. Cultural Dimensions in Contrast

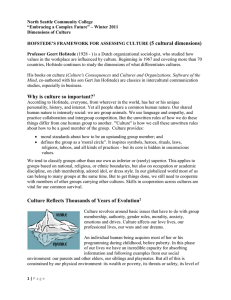

There are various ways to look at differences that people bring to issues and relationships out of their cultural background. We will look at two models that help us develop perspective of our personal cultural profile as it compares with that of people from another culture or country.

A. Model of Cultural Values

Time tension: Event vs. Time

Judgment tension: Holistic vs. Dichotomistic

Crisis management tension: Crisis vs. Non-crisis

Goal tension: Person vs. Task

Self-worth tension: Achievement vs. Status

Vulnerability tension: Vulnerability as strength vs. Vulnerability as weakness

From: S. Lingenfelter and M. Mayers. 1986. Ministering Cross-Culturally. Grand Rapids: Baker.

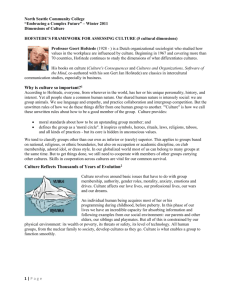

B. Geert Hofstede Cultural Dimensions:

Power Distance Index (PDI) that is the extent to which the less powerful members of organizations and institutions (like the family) accept and expect that power is distributed unequally. This represents inequality (more versus less), but defined from below, not from above. It suggests that a society's level of inequality is endorsed by the followers as much as by the leaders. Power and inequality, of course, are extremely fundamental facts of any society and anybody with some international experience will be aware that 'all societies are unequal, but some are more unequal than others'.

Individualism (IDV) on the one side versus its opposite, collectivism, that is the degree to which individuals are integrated into groups. On the individualist side we find societies in which the ties between individuals are loose: everyone is expected to look after him/herself and his/her immediate family. On the collectivist side, we find societies in which people from birth onwards are integrated into strong, cohesive in-groups, often extended families (with uncles, aunts and grandparents) which continue protecting them in exchange for unquestioning loyalty. The word 'collectivism' in this sense has no political meaning: it refers to the group, not to the state. Again, the issue addressed by this dimension is an extremely fundamental one, regarding all societies in the world.

Masculinity (MAS) versus its opposite, femininity, refers to the distribution of roles between the genders which is another fundamental issue for any society to which a range of solutions are found.

The IBM studies revealed that (a) women's values differ less among societies than men's values; (b) men's values from one country to another contain a dimension from very assertive and competitive and maximally different from women's values on the one side, to modest and caring and similar to women's values on the other. The assertive pole has been called 'masculine' and the modest, caring pole 'feminine'. The women in feminine countries have the same modest, caring values as the men; in the masculine countries they are somewhat assertive and competitive, but not as much as the men, so that these countries show a gap between men's values and women's values.

Uncertainty Avoidance Index (UAI) deals with a society's tolerance for uncertainty and ambiguity; it ultimately refers to man's search for Truth. It indicates to what extent a culture programs its members to feel either uncomfortable or comfortable in unstructured situations. Unstructured situations are novel, unknown, surprising, different from usual. Uncertainty avoiding cultures try to

3

Multicultural Teaming minimize the possibility of such situations by strict laws and rules, safety and security measures, and on the philosophical and religious level by a belief in absolute Truth; 'there can only be one Truth and we have it'. People in uncertainty avoiding countries are also more emotional, and motivated by inner nervous energy. The opposite type, uncertainty accepting cultures, are more tolerant of opinions different from what they are used to; they try to have as few rules as possible, and on the philosophical and religious level they are relativist and allow many currents to flow side by side.

People within these cultures are more phlegmatic and contemplative, and not expected by their environment to express emotions.

Long-Term Orientation (LTO) versus short-term orientation: this fifth dimension was found in a study among students in 23 countries around the world, using a questionnaire designed by Chinese scholars. It can be said to deal with Virtue regardless of Truth. Values associated with Long Term

Orientation are thrift and perseverance; values associated with Short Term Orientation are respect for tradition, fulfilling social obligations, and protecting one's 'face'. Both the positively and the negatively rated values of this dimension are found in the teachings of Confucius, the most influential Chinese philosopher who lived around 500 B.C.; however, the dimension also applies to countries without a Confucian heritage.

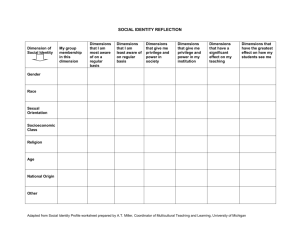

Country

Global

U.S.A.

Canada

Australia

Germany

Russia

Far East Asia

Japan

China

Philippines

U.S.A.:

PDI

55

40

39

36

35

93

60

55

80

94

IND

43

91

80

90

67

39

24

47

20

32

MAS

50

62

47

60

66

36

53

95

66

64

UAI

64

46

61

50

65

95

60

92

30

44

30

31

--

85

LTO

45

29

23

80

118

19

There are only seven (7) countries in the Geert Hofstede research that have Individualism

(IDV) as their highest Dimension: USA (91), Australia (90), United Kingdom (89), Netherlands and Canada (80), and Italy (76).

The high Individualism (IDV) ranking for the United States indicates a society with a more individualistic attitude and relatively loose bonds with others. The populace is more selfreliant and looks out for themselves and their close family members.

The next highest Hofstede Dimension is Masculinity (MAS) with a ranking of 62, compared with a world average of 50. This indicates the country experiences a higher degree of gender differentiation of roles. The male dominates a significant portion of the society and power structure. This situation generates a female population that becomes more assertive and competitive, with women shifting toward the male role model and away from their female role.

The United States was included in the group of countries that had the Long Term Orientation

(LTO) Dimension added. The LTO is the lowest Dimension for the US at 29, compared to the

4

Multicultural Teaming world average of 45. This low LTO ranking is indicative of the societies' belief in meeting its obligations and tends to reflect an appreciation for cultural traditions.

The next lowest ranking Dimension for the United States is Power Distance (PDI) at 40, compared to the world Average of 55. This is indicative of a greater equality between societal levels, including government, organizations, and even within families. This orientation reinforces a cooperative interaction across power levels and creates a more stable cultural environment.

The last Geert Hofstede Dimension for the US is Uncertainty Avoidance (UAI), with a ranking of 46, compared to the world average of 64. A low ranking in the Uncertainty Avoidance

Dimension is indicative of a society that has fewer rules and does not attempt to control all outcomes and results. It also has a greater level of tolerance for a variety of ideas, thoughts, and beliefs.

Canada:

Canada has Individualism (IDV) as the highest ranking (80) Hofstede Dimension, and is indicative of a society with a more individualistic attitude and relatively loose bonds with others. The populace is more self-reliant and looks out for themselves and their close family members. Privacy is considered the cultural norm and attempts at personal ingratiating may meet with rebuff.

The majority of Canadians, as well as citizens of other English speaking countries, (see United

Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, and the United States) have Individualism as their highest ranking Dimension.

Among high IDV countries, success is measured by personal achievement. Canadians tend to be self-confident and open to discussions on general topics; however, they hold their personal privacy off limits to all but the closest friends.

Canadian's lowest ranking Dimension is Long Term Orientation at 23, compared to the average of 45 among the 23 countries surveyed for which scores have been calculated. This low LTO ranking is indicative of societies' belief in meeting its obligations and tends to reflect an appreciation for cultural traditions.

Canada's Power Distance (PDI) is relatively low, with an index of 39, compared to a world average of 55. This is indicative of a greater equality between societal levels, including government, organizations, and even within families. This orientation reinforces a cooperative interaction across power levels and creates a more stable cultural environment.

It should be noted there is tension between the French province of Quebec and other

Canadian provinces. Citizens of Quebec tend to be more private and reserved.

China:

Geert Hofstede analysis for China has Long-term Orientation (LTO) the highest-ranking factor

(118), which is true for all Asian cultures. This Dimension indicates a society's time perspective and an attitude of persevering; that is, overcoming obstacles with time, if not with will and strength. (see Asian countries graph below)

5

Multicultural Teaming

The Chinese rank lower than any other Asian country in the Individualism (IDV) ranking, at

20 compared to an average of 24. This may be attributed, in part, to the high level of emphasis on a Collectivist society by the Communist rule, as compared to one of

Individualism.

The low Individualism ranking is manifest in a close and committed member 'group', be that a family, extended family, or extended relationships. Loyalty in a collectivist culture is paramount. The society fosters strong relationships where everyone takes responsibility for fellow members of their group.

Of note is China's significantly higher Power Distance ranking of 80 compared to the other

Far East Asian countries' average of 60, and the world average of 55. This is indicative of a high level of inequality of power and wealth within the society. This condition is not necessarily forced upon the population, but rather accepted by the society as their cultural heritage.

**There is a strong correlation between Christian faith (especially non-Catholic) and Individualism.

**Breakout:

From what you know, where would the greatest contrast be between your “home” culture and your

“host” culture?

Where would you anticipate the greatest contrast/conflict in potential team relationships?

Communication

Decision-making

Conflict resolution

Other?

IV. Stages of Team Development

Forming

Storming

Norming

Performing

V. Avoiding Five Key Dysfunctions of a Team

Absence of Trust – Trust each other!

Fear of Conflict – Engage in healthy debate!

Lack of Commitment – Commit to team decisions!

Avoidance of Accountability – Hold each other accountable!

Inattention to Results – Focus on team results!

Conclusion

SEND is committed to modeling the wonder of the unity and harmony of the Body of Christ in all of our relationships. We intentionally incorporate those from various ethnic and cultural backgrounds in the work of engaging the least reached to establish reproducing churches. This is not a natural process and demands much of each member of SEND. We are committed to recognizing our personal cultural profile and biases, and working together toward mutual understanding and cooperation to the glory of God in our teams and among the membership in each Area.

6

Multicultural Teaming

Resources:

CultureGPS Professional Edition. iTunes – application for use with iPhone or iPod Touch, compares five-dimension cultural profiles and distinctives of 98 countries and 3 regions with insights on interacting in team or management relationships in international business. Released Nov.

2008.

Elmer, Duane H. 2006. Cross-cultural Servanthood: Serving the World in Christlike Humility.Downers

Grove, Illinois: InterVarsity Press.

Hofstede, Geert. 2001. Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions and

Organizations Across Nations. Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Sage Publications.

____________. 2005. Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind. New York: McGraw-Hill

Publishers.

Lencioni, Patrick. 2002. The Five Dysfunctions of a Team. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Lingenfelter, Sherwood G., and Marvin K. Mayers. 1986. Ministering Cross-Culturally: An

Incarnational Model for Personal Relationships. Grand Rapids: Baker.

Lingenfelter, Sherwood G., and Judith E. Lingenfelter. 2003. Teaching Cross-Culturally: An

Incarnational Model for Teaching and Learning. Grand Rapids: Baker.

Lingenfelter, Sherwood G. 2008. Leading Cross-Culturally: Covenant Relationships for Effective

Christian Leadership. Grand Rapids: Baker.

7