Jelenciakova_Pr _their_Registrability

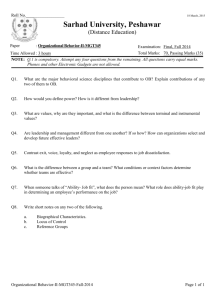

advertisement