JC S - jessbarga

advertisement

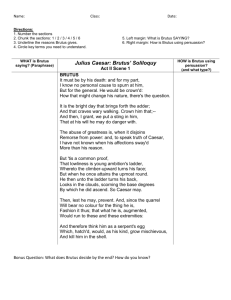

Sample commentary essay: Julius Caesar, William Shakespeare – pp. 61 – 63 [Raw passage without my annotations from commentary planning] Brutus: It must be by his death; and for my part, 10 I know no personal cause to spurn at him, But for the general. He would be crowned. How that might change his nature, there's the question. It is the bright day that brings forth the adder, And that craves wary walking. Crown him that, 15 And then, I grant, we put a sting in him, That at his will he may do danger with. The abuse of greatness is when it disjoins Remorse from power; and, to speak truth of Caesar, I have not known when his affections swayed 20 More than his reason. But 't is a common proof, That lowliness is young ambition's ladder, Whereto the climber-upward turns his face: But when he once attains the upmost round, He then unto the ladder turns his back, 25 Looks in the clouds, scorning the base degrees By which he did ascend; so Caesar may; Then, lest he may, prevent. And, since the quarrel Will bear no colour for the thing he is, Fashion it thus: that what he is, augmented, Would run to these, and these extremities: And therefore think him as a serpent's egg, Which, hatched, would, as his kind, grow mischievous, And kill him in the shell. 30 [Annotated passage from commentary planning – includes all notes, even those not used] possible devices: alliteration [with assonance & consonance, and meter], contradiction, high diction, understatement, metaphor/simile/personification, crescendo or building argument Brutus: It must be by his death; and for my part, 10 I know no personal cause to spurn at him, contradiction But for the general. He would be crowned. How that might change his nature, there's the question. implied rhetorical question It is the bright day that brings forth the adder, metaphor And that craves wary walking. Crown him that, 15 And then, I grant, we put a sting in him, understatement That at his will he may do danger with. ? The abuse of greatness is when it disjoins high diction (extended) Remorse from power; and, to speak truth of Caesar, I have not known when his affections swayed 20 More than his reason. But 't is a common proof, That lowliness is young ambition's ladder, metaphor, personification Whereto the climber-upward turns his face: (extended) But when he once attains the upmost round, He then unto the ladder turns his back, 25 Looks in the clouds, scorning the base degrees By which he did ascend; so Caesar may; Then, lest he may, prevent. And, since the quarrel Will bear no colour for the thing he is, Fashion it thus: that what he is, augmented, 30 Would run to these, and these extremities: And therefore think him as a serpent's egg, Which, hatched, would, as his kind, grow mischievous, And kill him in the shell. (metaphor/simile) Commentary: In this passage, which occurs toward the beginning of Act II, Brutus engages in an eloquent late-night soliloquy that strengthens his resolve to assassinate Julius Caesar. At this point in the play, Cassius has already set his conspiracy in motion, and Brutus has noted what he believes to be Caesar’s growing lust for the crown: the combination of his friend’s persuasion and his own suspicions causes Brutus to feel increasingly uneasy about Caesar’s rising star. During the soliloquy, Brutus muses to himself while his servant is away; his tone is studied and rational throughout, giving the impression that his potential participation in the conspiracy may be a logical response to his concern for Rome, despite his admitted lack of evidence against Caesar. By lacing the speech with understatement; composing it in high, reasoned diction; and building it around several strong metaphors, Shakespeare characterizes Brutus as wise and principled leader who founds his decisions in reason rather than passion. Although Brutus reveals from the outset that any possible plan to restrain Caesar “must be by his death” (10), he goes on to mask his plans rhetorically through understatement. Brutus is well aware that Cassius means for them all to kill Caesar by stabbing him to death; however, when he refers to the act, he says instead that they will “put a sting in him” (16). Later, when he examines the likely outcome of Caesar’s political climb, he indicates that the conspirators must merely “prevent” the senator from reaching the top (28). Finally, he characterizes his issues with Caesar as a “quarrel” (28), resulting from Caesar’s transformation from a rational to a “mischievous” force (33). All of these terms downplay the true object of Brutus’ reflection – namely, an impassioned attempt to preserve Rome from evil ambition by means of a bloody assassination – and thus make it easier for him to reach his conclusion. It is only at the end of his speech, when Brutus has satisfied himself with the counts he levels against Caesar, that he again uses direct language, stating that the conspirators must “kill him in his shell” (34), but even this blunt verb is couched within an extended metaphor likening the ruler to a snake. The diction Shakespeare uses to give Brutus his measured tone is consistently elevated and rational, signaling Brutus’ intelligence and good sense. In contrast to Brutus’ earlier monologues when he was racked with doubt about the conspiracy, by this point he seems to have come to terms with the emotional betrayal of his dear friend, and is viewing the plan in a cold and rational light. Brutus admits candidly that he “know[s] no personal cause to spurn at ” Caesar, but that the better good of Rome compels him to do so (11); as he proceeds through his argument, he lapses into high diction and platitudes, declaring, “The abuse of greatness is when it disjoins / Remorse from power” (18-19). Later, Brutus maintains his lofty, elegant, and highly connotative diction when he describes how an ambitious climber like Caesar “looks in the clouds, scorning the base degrees / By which he did ascend,” using the weight of poetry to move his audience against his foe (26-27). Throughout the passage, Brutus recurs to high-register verbs such as “spurn” (11), “craves” (15), “grant” (16), “swayed” (20), “attains” (24) and “scorning” (26), persuading both himself and the audience at once. The greatest weapons with which Brutus arms himself in this internal battle are his reason and eloquence, and these are what lead him to craft the intricate metaphors that bear most of the weight of the passage. First, Brutus indicates that Caesar has reached a “bright day” when his military and political glory are at their peak, and that such is the day that “brings forth the adder,” or causes the evil, deceptive side of a leader to come to the surface, requiring others to take measures to protect the nation (14). The comparison to a day emphasizes the temporal nature of Caesar’s climactic popularity; the link between Caesar and a snake, which will be extended to the end of the passage, fortifies Brutus’ conviction that he is low, weak, and devious. Next, Brutus considers ambition, comparing Caesar’s to a climber on a ladder who may be devoted to his followers and his modest beginnings as he rises, but who, “when he once attains the upmost round” . . . “then unto the ladder turns his back” . . .”scorning the base degrees / By which he did ascend” (24-27). Here, Brutus illustrates the threat to a nation that a leader who ceases to prioritize his people can pose, drawing what appears to be a logical conclusion about Caesar’s potentially poisonous effect on Rome, even in the absence of its evidence. Finally, closing his arguments with his strongest metaphor, Brutus returns to the snake image, likening Caesar to “a serpent’s egg” that is not yet but will surely grow to be dangerous when “hatched,” effectively justifying his plans to join Cassius in “kill[ing] him in the shell” before he can do any harm to Rome (32-34). Closing with this final simile, Brutus uses a logical progression of metaphors to rationalize the slaying of his close friend. Through an array of persuasive literary devices such as understatement, diction and metaphor, Shakespeare uses Brutus’ soliloquy to characterize his rational and deliberate thought process, demonstrating to the audience how a devoted friend establishes the necessity of the bloody betrayal of a close friend. This characterization is helpful in building the implicit contrast between Brutus and Antony that develops through the last three acts of the play: Brutus’ dispassionate, lucid, and honorable thought process and Antony’s hot-blooded, emotional manipulation are represented as polar opposites, neither of which is a sufficient foundation for making decisions when not tempered by the better parts of the other. Brutus relies on logic to dictate his course rather than accepting the love and loyalty that should play a part in governing the relations between men: this fatal flaw is ultimately his undoing.