PowerPoint discussion and assignment

advertisement

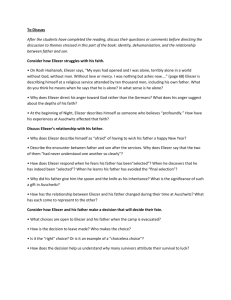

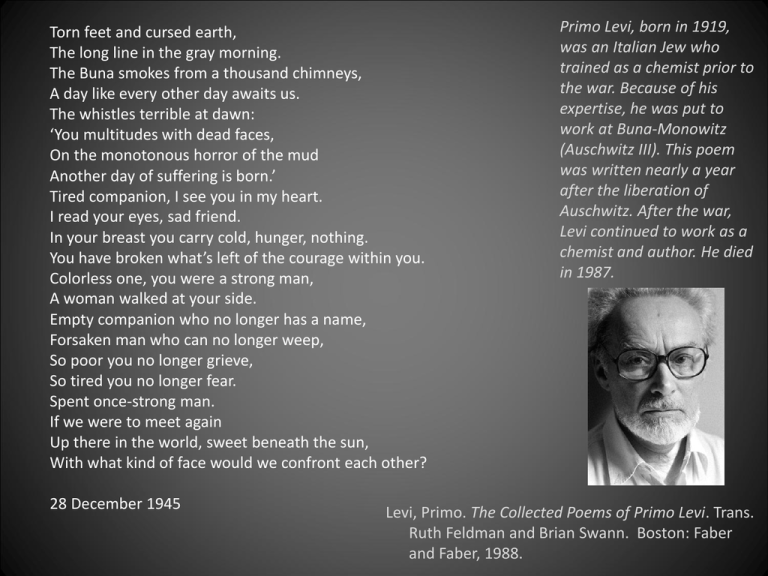

Torn feet and cursed earth, The long line in the gray morning. The Buna smokes from a thousand chimneys, A day like every other day awaits us. The whistles terrible at dawn: ‘You multitudes with dead faces, On the monotonous horror of the mud Another day of suffering is born.’ Tired companion, I see you in my heart. I read your eyes, sad friend. In your breast you carry cold, hunger, nothing. You have broken what’s left of the courage within you. Colorless one, you were a strong man, A woman walked at your side. Empty companion who no longer has a name, Forsaken man who can no longer weep, So poor you no longer grieve, So tired you no longer fear. Spent once-strong man. If we were to meet again Up there in the world, sweet beneath the sun, With what kind of face would we confront each other? 28 December 1945 Primo Levi, born in 1919, was an Italian Jew who trained as a chemist prior to the war. Because of his expertise, he was put to work at Buna-Monowitz (Auschwitz III). This poem was written nearly a year after the liberation of Auschwitz. After the war, Levi continued to work as a chemist and author. He died in 1987. Levi, Primo. The Collected Poems of Primo Levi. Trans. Ruth Feldman and Brian Swann. Boston: Faber and Faber, 1988. Section 4 Overview At Buna, Eliezer and his father endure routine humiliations and random violence. At one point, a Kapo’s assistant tries to take Eliezer’s shoes. Sometime later, a Kapo demands the gold crown on his tooth. On yet another occasion, Eliezer is beaten for no reason at all. At the same time, his father is finding it harder and harder to keep up. Eliezer is torn between anger at him for not knowing how to march and his love for the man. More and more, Eliezer feels he is becoming a “starved stomach.” Although a public hanging troubles him briefly, he and the other men are too hungry to think much beyond their dinner. Then a child and two adult prisoners are hanged for hiding weapons. Watching the boy slowly die, a prisoner asks, “For God's sake, where is God?” Eliezer, deeply moved by the hanging, hears a voice answer, “Where He is? This is where –-hanging here from this gallows.…” (page 65) Consider Elie’s relationship with his father. Give examples of the ways Eliezer’s relationship with his father is changing. What is prompting those changes? How do the changes in his relationship with his father affect the way Eliezer sees himself as an individual? The way he views his father? What does Eliezer mean when he refers to his father as “his weak point”? Is love a human weakness? Consider how the process of dehumanization affects Eliezer and his fellow prisoners. How do words like soup and bread take on new meaning for Eliezer? Why does he describe himself as a “starved stomach”? What did it mean to see bread and soup as one’s “whole life”? (page 52) Eliezer describes two hangings in this section. He tells the reader that he witnessed many others. Yet he chose to write only about these two. Why are these two hangings so important to him? How do they differ from the others? 1.Reread pg 61 – 63. Why did the soup “taste better than ever”? 2.Reread pg 63 – 65. Why did the soup “[taste] of corpses”? Consider how the process of dehumanization affects Eliezer and his fellow prisoners. Why do you think the Germans chose to hang a few prisoners in public at a time when they are murdering thousands each day in the crematoriums? When the young boy is hanged, a prisoner asks, “For God's sake, where is God?” Eliezer hears a voice answer, “Where He is? This is where–-hanging here on this gallows.…” What does this statement mean? Consider the meaning of the word resistance at Auschwitz. What does the word resistance mean to you? Some insist that “armed resistance” is the only form of legitimate resistance. Can you resist without the physical means of defeating your opposition? Others stress the idea that resistance requires organization. Does resistance need a unified plan in order to be effective? Still others argue that resistance is more about the will to live and the power of hope than it is about either weapons or organization. Do you agree? Why or why not? Consider the meaning of the word resistance at Auschwitz. Are the following examples of resistance? If so, who are what are they resisting? • “I refused to give him my shoes. They were all I had left” (48). • Eliezer’s refusal to let the dentist remove his gold crown (51 – 52). • The French girl’s decision to speak in German to Eliezer after he is beaten (53). • Elie’s sacrifice of his gold crown to protect his father (54-56). • The prisoner’s choice to die for soup (59 – 60). • The prisoners who attempted to stockpile weapons, for which they were later hanged Consider the behaviour of other inmates from Wiesel’s perspective. Elie Wiesel said the following of cruel or violent inmates: No one has the right to judge them, especially not those who did not experience Auschwitz or Buchenwald. The sages of our Tradition state point-blank: “Do not judge your fellow-man until you stand in his place.” In other words, in the same situation, would I have acted as he did? Sometimes doubt grips me. Suppose I had spent not eleven months but eleven years in a concentration camp. Am I sure I would have kept my hands clean? No, I am not, and no one can be. Wiesel, Elie. All Rivers Run to the Sea: Memoirs. New York: Knopf, 1995. Consider the behaviour of other inmates from Wiesel’s perspective. Wiesel writes that he prefers to remember “the kindness and compassion” of his fellow prisoners rather than those who were cruel or violent. Assignment: Identify examples found thus far in the book. Add this to your Learning Log Acts of Kindness and Compassion Acts of Cruelty and Violence In what way are all of these people victims?