Financial - Carleton University

advertisement

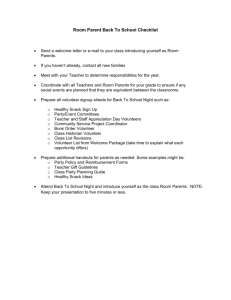

http://home.oise.utoronto.ca/~lmook/carleton0206.htm Agenda: February 27, 2006 9:00 - 9:30 Introductions 9:30 – 10:30 Introduction to Social Accounting 10:30 – 10:45 Break 10:45 – 12:00 Case Study: CCI 12:00 – 12:45 Lunch 12:00 – 2:00 Work Group: OCLF What is Social Accounting? 35 years old Long on critique, primarily of profit-oriented firms narrowness of accounts, externalities Short on working models Not applied to non-profits or co-operatives Our Definition of Social Accounting “A systematic analysis of the effects of an organization on its communities of interest or stakeholders, with stakeholder input as part of the data that is analyzed for the accounting statement” Broadens the domain of items that are included in accounting statements so that social organizations can better tell their story Quarter, Mook & Richmond (2003) Social Economy Viewpoint Separation between social and economic artificial Economic effects have social consequences Social effects have economic consequences Critique of Conventional Accounting Conventional accounting limited to market transactions specific to the organization excludes nonmonetized inputs and outputs—for example, Volunteer contributions/social labour (unpaid member contributions) in mutual associations and co-ops Environmental impacts Presumes that profit reflects and promotes the optimal distribution of limited resources Thus profits, and in turn shareholder returns, are a measure of success, and the resulting behaviour is that profit organisations try to maximize them Critical Accounting The very act of “counting” certain things and excluding others shapes a particular interpretation of social reality, which in turn has policy implications For example, what should "assets" and "liabilities" include/exclude? The answers to questions such as these define the "size," "health," "structure" and "performance" of an organisation From this perspective, the accounts of an organization do not just describe or communicate information about an organisation, but they define its boundaries and shape behaviour Social Economy Public Sector Private Sector Public Sector Nonprofits (B) Social Economy (A), (B), (C) MarketBased Coops and Nonprofits (A) Civil Society Organization s (C) Quarter, Mook & Richmond (2003) Social Economy Some criteria: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. the organization’s statement of purpose emphasizes its social objectives (not necessarily to the exclusion of economic and other objectives) and the social objectives are manifest in its practice; the organization generates some economic value through the services it provides and purchases that it undertakes; the organization is not a government agency, and either has a separate incorporation or formal structure as well as a self-governing character that places it at arm's length from government, government funding—even extensive government funding—notwithstanding; for an organization whose earnings either are predominantly or exclusively from market exchanges, the prerogatives of capital (for example, rate of return, capital valuation) do not dominate over social objectives in its decision making; membership is voluntary and non-discriminatory according to the human rights code; organizations in the social economy provide a venue for civic engagement: engaging people in democratic practices, which may or may not lead to harmony. Quarter (2005) Discussion What behaviours are promoted in current accounting models for social economy organizations and why? In designing new accounting models, what behaviours do we want to promote/change? Break Examples of Recent Case Studies Value Added by Volunteers Canadian Breast Cancer Foundation, Ontario Chapter Canadian Crossroads International Jane/Finch Community and Family Centre Junior Achievement of Rochester, New York Canadian Red Cross, Toronto Region Waterloo Co-operative Residence Inc. Sustainable Building Economically Targeted Investments of Pension Funds Upcoming: Evergreen Commons at the Brick Works Why Report Volunteer Value Excluding volunteer labor in nonprofit accounting statements undervalues a key resource that many nonprofits rely on Including volunteer value within accounting statements provides a more complete picture of the organization’s performance To help funders and donors understand the impact of their investment in the organization To demonstrate the value of volunteers to the organization, the community and policy makers Context Canada 2003: 19 million ‘formal’ volunteers 2 billion hours 7 percent in governance 93 percent in delivering programs/services and fundraising Equivalent to 1 million full-time jobs Virtually all non-profits rely on volunteers to some degree Over half rely solely on volunteers to fulfill their mission (only 46 percent have paid staff) Statistics Canada (2004) Context Statistics Canada (2005) Context Statistics Canada (2005) Context Statistics Canada (2005) Three ways to account for volunteer value 1. 2. 3. As a percentage of all human resources As a percentage of resources received Expanded Value Added Statement Canadian Crossroads International Selected Findings 15-month fiscal period 27 full-time equivalent (FTE) paid staff 609 volunteers contributed: 152,643 hours in the year of the study, or 67 FTEs out-of-pocket expenses totalling $131,029 for which they did not claim for reimbursement Host families also had un-reimbursed out-of-pocket expense totalling $36,143 1.Volunteer FTE hours as a percentage of total human resource hours Information required: 1. 2. FTE of volunteers: 67 FTE of paid employees 27 Total FTE: 67 + 27 = 94 1.Volunteer FTE hours as a percentage of total human resource hours 2.Volunteer contributions as a percentage of total resources received Information required 1. Comparative market value of hours contributed by volunteers Hours contributed by volunteers multiplied by comparative market value rate 2. 3. Out-of-pocket expenses paid by volunteers and host families but not reimbursed (from survey) Total monetary revenues received (from financial statements) Estimating a comparative market value of hours contributed by volunteers Opportunity Cost What is an hour of your time worth to the volunteer? Replacement Cost What is an hour of your time worth to the organization? Mook & Quarter (2004) 2.Volunteer contributions as a percentage of total resources received 15 months Board Committees Animateurs Sub-total Overseas To Canada Interflow Net Corps Sub-total Total # hrs 2,047.5 45,990 1,750 49,788 69,400 23,645 685 9,125 102,855 152,642.5 Rate $28.39 $22.465 $19.08 $25.85 $19.08 $19.08 $25.85 Amount $58,129 1,033,165 33,390 $1,124,684 $1,793,990 451,147 13,070 235,881 $2,494,088 $3,618,772 2.Volunteer contributions as a percentage of total resources received Financial: Revenues received (from financial statements) $3,853,596 Social: Value of volunteer hours contributed $3,618,772 Value of volunteer & host family out-ofpocket expenditures not reimbursed $131,029 + $36,143 $3,785,944 Total $7,639,540 2.Volunteer contributions as a percentage of total resources received 3. Expanded Value Added Statement (EVAS) A supplemental accounting statement based on the Value Added Statement used in the United Kingdom, South Africa and other countries Value Added Statement Proposed in 1954 by Waino Suojanen, a Harvard MBA and economics PhD student at UC Berkeley, to measure the contribution of an organization to society Similar to the income statement in that it uses the same figures and accounts, but significantly different in that it makes the assumption that an enterprise is responsible to all participants and not only to its stockholders. What is value added? Value added measures the wealth that an organization creates by adding value to raw materials, products and services through the use of labour and capital Calculated as: value of final products/services minus value of externally purchased goods and services Raw Materials $1.00 Value Added Final Product $3.00 Raw Materials $1.00 Value Added $2.00 Final Product $3.00 Outputs Direct Indirect 3. Expanded Value Added Statement (EVAS) Information required to report volunteer value in EVAS: 1. 2. 3. Financial statements Comparative market value of volunteer hours Out-of-pocket expenses not reimbursed Back to the CCI Financial: Total Expenditures $3,912,720 Social: Value of volunteer hours contributed $3,618,772 Value of volunteer out-of-pocket expenditures not reimbursed $131,029 + $36,143 $3,785,944 Comparative Market Value of Primary Outputs $7,698,644 3. Expanded Value Added Statement (EVAS) 3. Expanded Value Added Statement (EVAS) Reporting: EVAS Disclaimer “This statement provides social data to accompany the organization’s financial report. It is specific to the year and circumstances reported. It cannot be used to compare with results from other organizations or this organization at other times. It is provides a partial account of the value of volunteer contributions.” 3. Expanded Value Added Statement (EVAS) The Expanded Value Added Statement takes a broader look at an organization integrates social and financial information takes a stakeholder approach the particular example in this presentation highlights the role of volunteers, but it can be modified to include other social and environmental impacts Skills development Environmental impacts Discussion Risks and Benefits Discussion What behaviours are promoted in current accounting models for non-profits and why? In designing new accounting models, what behaviours do we want to promote/change? Lunch Ontario Community Loan Fund Labour hours 16% Paid Staff Volunteers 84% 8% 1% 7% Interest on Loans 18% City of Ottawa Trillium 42% Donations Application fees Investment Income 24% Including volunteers 6% 1% 6% Interest on Loans 20% City of Ottawa 33% Trillium Donations Volunteer hours Application fees 15% Investment Income 19% Expanded Value Added 24% Financial Social 76% Ideally … Low cost Not time consuming Easy to use and analyze Easy to present results No need for extensive training Results can be used by beneficiaries, staff as well as by funders and government officials Takes into consideration … CED core values and beliefs Different stakeholders, for example: Funders/donors Government officials Staff Beneficiaries References Mook, Laurie & Jack Quarter (2003). How to assign a monetary value to volunteer contributions. Toronto: Canadian Centre for Philanthropy. Available from Internet URL http://www.kdc-cdc.ca/ Quarter, Jack, Laurie Mook & Betty Jane Richmond (2003). What counts: Social accounting for nonprofits and cooperatives. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. Richmond, Betty Jane (1999). Counting on each other: A social audit model to assess the impact of nonprofit organizations. Ph.D. diss., University of Toronto. Statistics Canada (2004). Cornerstones of community: Highlights of the national survey of nonprofit and voluntary organizations. Available from Internet URL http://www.statcan.ca/ Statistics Canada (2005). Satellite account of nonprofit institutions and volunteering. Ottawa: Ministry of Industry. Available from Internet URL http://www.statcan.ca Suojanen, Waino W. (1954). Accounting theory and the large corporation. The Accounting Review 29 (3): 391-398. Thank you! Contact information: Laurie Mook, OISE/University of Toronto Social Economy Centre 252 Bloor St. W., Toronto, Ontario M1L 3S9 Email: Lmook@oise.utoronto.ca Website: http://socialeconomy.utoronto.ca http://home.oise.utoronto.ca/~lmook/carleton0206.htm