ANSWERS TO THE REVIEWERS' REPORTS Reviewer 1

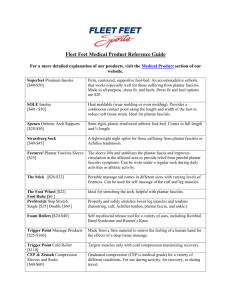

advertisement

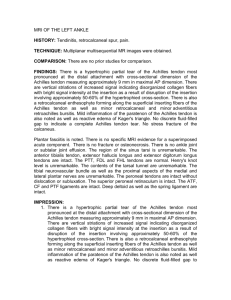

ANSWERS TO THE REVIEWERS’ REPORTS Reviewer 1 The cohort of the study consisted of 48 consecutive ambulant or potentially ambulant patients with spastic paralysis due to cerebral palsy. The majority of the patients were hemiplegic and diplegic, while only 4 were tetraplegic with limited ambulation. One of our prerequisite for split tibialis tendon transfers was the ability of the patients for walking or the potential of standing and ambulation, as it is unnecessary to restore the muscle balance of feet in nonambulatory patients. In these cases, the deformity can be corrected in a later stage by performing bone surgery. The underlying cause of the foot deformity in both groups were the cerebral palsy, which is a non-progressive neurological condition, justifying thus better final results than any other progressive one. Reviewer 2 It was referred that no revisions needed. Reviewer 3 Major In the contrary, we mentioned that although the gait analysis and the dynamic EMG are of a great importance, they are not available in every Institution. It is suggested not only from us but from the recent literature as well the use of these tools for diagnostic purposes. For the completion of our study this was not available. The overactivity of PT causes not only varus but equinus hind-foot deformity as well, and the cause of the deformity cannot be clinically identified in some cases, especially when Achilles shortening co-exists. Under these circumstances, we can intraoperatively identify the percentage of the equinus due to Achilles shortening and/or to posterior tibial tendon overactivity. It is corrected through the whole text that one of the inclusion criteria is the patients to be ambulant or potentially ambulant. The equinus position of the hindfoot should be addressed if it is >5°. The plantar soft tissue release is the Steindler procedure (open release of the plantar aponeurosis+release of the plantar muscles from their insertion to the calcaneus). 1 We used tables to indicate the results as a percentage according to the involvement, the supplementary operations performed concomitant with the main operation (SPLATT) and supplementary operations performed concomitant and after the main operation (SPOTT). Evaluation of the results was carried out using the clinical criteria of Hoffer et al in group one and Kling and Kaufer in group two. All figures have been re-arranged in a more suitable way so as to be clearer to the reader. Minor All the corrections concerning the English language were addressed. Additionally: Line 19: all the deformities were flexible as mentioned concerning the inclusion criteria Line 33: the muscle-tendon unit is contracted Line 40: index operation (main procedure) Line 58: spasticity of the gastrocnemius-soleus complex which turns into tightness after a long period of time. Line 83: a sliding lengthening of the Achilles (Hoke procedure) was performed. Reviewer 4 The aim of the study has not been expressed properly as our goal was “to identify the causative muscle producing the deformity and apply the most suitable technique”, as the cause of the deformity was the cerebral palsy, a non-progressive neurological condition. As two different clinical assessments of outcome between the two groups have been used, our intention was not to compare against each other, but to identify the muscle causing the deformity and performing the appropriate technique as the deformity can be clinically unidentifiable in some cases, when Achilles shortening co-exists producing foot equinus. We performed the Hoke procedure (sliding technique) for the Achilles lengthening in 18 feet. The cavus component was presented in feet which underwent supplementary operations performed concomitant with the index operation. The two major additional operations that have been performed were: the plantar soft tissue 2 release, the most common out of these procedures, as it lengthens the shortened base of the foot, and its contribution to the successful outcome for the correction of the cavus component cannot be overemphasized, and the the extensor tendons transfer to the metatarsals which aimed to improve the metatarsophalangeal dysfunction, to enhance ankle dorsiflexion and in association with the transcutaneous flexor tenotomies in several toes to correct the clawing. In complex deformities, other supplementary procedures may be required to achieve the best possible outcome. It could be argued that the validity and reliability of our results may have been affected by the assessors used being closely involved with the design of the study and measurement of outcomes, thus allowing for a possible experimenter bias. However, the patients were seen by two independent orthopaedic surgeons, and the range of objective and subjective outcome data used led us to conclude that there was sufficient triangulation for the results to be seen as reliable. Additional corrections by authors 1. The abbreviations for split anterior and posterior tibial tendons have been corrected to SPLATT and SPOTT. The purpose of doing split tendon transfers instead of whole transfers in children with cerebral palsy has been included to the discussion. 2. It was clarified though the text according to the inclusion criteria that the children should be ambulators or potentially ambulators. Patient’s status in Fig 1c was potentially ambulatory becoming full ambulatory postoperatively. We divided the study groups into those with more prominent forefoot and midfoot inversion (group I) and those with more prominent hindfoot varus (group II) and proposed the SATT for group I and the SPTT for group II. Patient in Figs 1d, 2d was an isolated forefoot and midfoot inversion and was treated by SPOTT. 3. The split lateral half of the tendon was passed into the holes made in the cuboid and sutured either to itself under moderate tension whenever there was sufficient length, or we performed the technique of anchoring the stump (pull- out wire, suturing to the periosteum etc). See surgical procedure part. 3