The Weather Channel and weather.com

advertisement

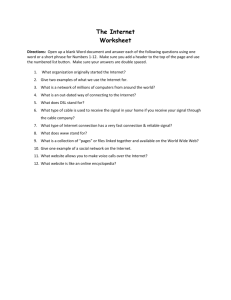

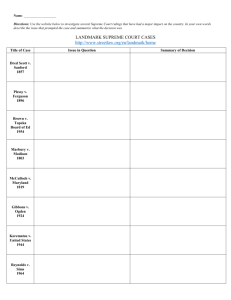

The Eye of the Storm: The Turbulent Rise of the Weather Channel Allison Chin, Jordan Esten, Kathryn Gadkowski, Peter Holzaepfel, Elizabeth Morbeck, Jessica Powers 11/11/2011 ENTREPRENEURSHIP AND INNOVATION STRATEGY TUCK SCHOOL OF BUSINESS Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 2 Landmark’s Hunt for Undiscovered Media Properties: The Growth of Telecable........................................ 3 The Fight that Changed Everything: The Advent of Satellite Distribution ................................................... 4 The Big Idea: A 24/7 Weather Channel ........................................................................................................ 4 Expectations of Opportunity and Size........................................................................................................... 5 The Innovation Ecosystem ............................................................................................................................ 6 Unrealistic Expectations: The Weather Channel Struggles for Survival ..................................................... 11 An Evolution in the Ecosystem: Cable Operators Need More .................................................................... 12 Leading the Ecosystem................................................................................................................................ 13 Carryover Into New Businesses .................................................................................................................. 14 First Mover Advantage: The Weather Channel and weather.com ............................................................. 15 Conclusion ...................................................................................................... Error! Bookmark not defined. Introduction On July 5th2008 Landmark Communications, a privately held, family owned media company headquartered in Virginia, entered into a definitive agreement to sell The Weather Channel Companies (TWCC) for $3.5 billion to a consortium of buyers including NBC Universal, the Blackstone Group and Bain Capital.1 During its 26 year history, TWCC became the market leader in providing weather information on TV and on the Internet. From its launch in 1982, The Weather Channel grew from a single cable network to a cross platform media company with multiple businesses. In 2008, The Weather Channel (TWC) cable network reached 96 million TV households.2 TWCC was the #1 provider of weather related content and The Weather Channel brand was one of the most recognized and trusted media brands in the U.S.3 TWCC became Landmark’s most lucrative asset, accounting for 25% of the company’s estimated $2 billion plus revenue in 2007.4 When analyzing the launch and subsequent growth of The Weather Channel, it is apparent that Landmark Communications had a flawed strategy based on unrealistic expectations about the growth of cable television and only achieved success because of an unexpected change in the cable ecosystem. Landmark buys two cable television franchises and begins operating them as TeleCable 1954 1964 CNN launches with 1.7 million subscribers 1975 Frank Batton joins Landmark HBO transmits Ali-Frazier bout nationally 1 Landmark launches TWC with 4.2 million subscribers ESPN launches with 1.0 million subscribers 1979 1980 Compuvid develops a system to display weather information on television screens, (precursor to WeatherStar) The Weather Channel reaches 9.4 million subscribers May 8 1981 1982 1983 1984 TWC partners with WSI to manage NWS data Struck deal with National Weather Service for data in a standardized format 15 largest cable operators sign deals to pay TWC 5 cents per subscriber Deborah Kinzer and Michael Altberg, “The Weather Channel Companies Rated 'B+'; Secured Loan Rated 'BB' (Recovery Rating: 1),” S&P Ratings Services 14 Aug. 2008. 2 Ibid 3 Connie Sage, Frank Batten, The Untold Story of the Founder of The Weather Channel (Charlottesville: University of Virgina Press 2011) 4 Philip, Walzer, “Landmark Completes Sale of the Weather Channel to NBC,” The Virginian-Pilot 13 Sept. 2008 Landmark’s Hunt for Undiscovered Media Properties: The Growth of Telecable Frank Batten took over the role of President of Landmark Communications from his uncle, Colonel Samuel Slover in 1954. Overnight, the 27 year old became head of a newspaper publishing company that had nearly 500 employees and grossed $8.7 million.5 With experienced Landmark veterans running the newspaper business, Batten focused his attention on finding ways to grow the company. With competition in the newspaper business picking up, Batten looked for a “media business that hadn’t yet been discovered.”6 In 1964, Landmark bought its first cable franchise and started a cable operating business under the name Telecable. Telecable became a profitable business for Landmark and a key factor in the company’s ability to start The Weather Channel. When Landmark entered into the cable television business, the industry was in its infancy. In those days, cable television was simply a central antenna that supplied television pictures to rural towns that were too distant from television transmitters to receive strong signals. Barriers to entry were low but capital intensive. To enter a market, cable operators acquired the franchise from the local government, built an antenna that could receive distant signals and modulate them onto coaxial cables, and connected the cables to subscribers’ homes by hanging the wires on existing telephone and power poles.7 Before cable television was invented, people put 20 to 30 foot antennas on top of their homes in order to pick up distant local broadcast television signals. Cable television was a much better technology because it provided customers with a much more reliable, higher quality picture. Telecable’s strategy for growth was to develop cable franchises in areas where cable systems did not previously exist. By building cable operations from the ground up, Telecable was able to take advantage of capital expenditure tax write-offs and each franchise earned a quick return on capital. A far superior technology to antennas, the demand for cable was high and household penetration averaged 90% for Telecable franchises.8 By the time Landmark Communications launched The Weather Channel, Telecable had a subscriber base of several million people, which provided The Weather Channel a guaranteed audience. 5 Frank Batten and Jeffrey Cruikshank The Weather Channel: The Improbable Rise of a Media Phenomenon (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 2002) 6 Ibid 7 Ibid 8 Ibid The Fight that Changed Everything: The Advent of Satellite Distribution Before the 1970s, television program providers relied on land based towers to pick up and relay television broadcast signals across long distances. These towers were heavily regulated by the FCC and costly to build. Heavy rain or electrical interference caused signal problems. Without the ability to easily send signals across cable systems, program providers did not have the ability to capture the large audiences necessary to earn substantial revenue from advertising to cover capital and operating expenses. As a result, cable operators had few options for the content that was broadcast. In the early days, cable television programming was limited to content produced by low quality, local program providers. In some cases, cable operators resorted to filming gold fish swimming in fish bowls to fill the channels on their stations. In 1975, however, HBO used satellite technology to transmit the Ali-Frazer boxing match to subscribers nation-wide. The ability to broadcast programming to a national audience represented an evolution in technology that changed the cable ecosystem and sparked the growth of the cable industry. Broadcast satellites were, not surprisingly, astronomically expensive. Individual program providers could not afford the capital investment to launch and maintain these devices. Each satellite, however, had room for multiple transponders to beam different programs signals back to earth and across cable networks. The key for Landmark was not launching its own satellite, but instead leasing a transponder on a currently operating satellite. An additional challenge facing program providers was leasing a transponder on a desirable satellite. Each satellite transmitted a different signal that required cable operators to invest in a different dish to receive the specific satellite broadcast signal. Dishes cost between $75,000-100,000, a cost that limited the number of dishes cable operators were willing to purchase.9 In order to reach the largest audience possible, it was critical to lease a transponder on a satellite dish with a high cable operator penetration rate. The Big Idea: A 24/7 Weather Channel By the late 1970’s, the cable operator industry was saturated and opportunities for further expansion were limited. In search of the next growth opportunity, Landmark looked to the program provider business. With its success in the newspaper business, Landmark believed there was great opportunity in a 24 hour cable news station.10 9 Frank Batten and Jeffrey Cruikshank The Weather Channel: The Improbable Rise of a Media Phenomenon (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 2002) 10 Ibid Just as Landmark was about to move forward with its new idea, Landmark President Frank Batten was diagnosed with throat cancer and the project was put on hold. After two years of treatment, Batten was ready to reconsider a move into television programming. By 1980, however, the program provider field was more crowded and Ted Turner had already launched both CNN and Headline News. At the time, cable television only included twelve channels and the demand for another news channel was limited. After exploring several opportunities within the television industry, Batten and his team at Landmark found one idea that many venture capital firms had previously passed on – a 24 hour weather station. While others envisioned a 24 hour station focused on national and regional weather, Batten and his team at Landmark believed that detailed local weather information in additional to national forecasting was the critical element to make the channel valuable to viewers.11 Beyond attracting a strong viewer base and the necessary advertising revenue to sustain its operations, building the type of weather channel that Landmark envisioned would require access to vast amounts of weather data and new technology to deliver both national and localized weather information. Expectations of Opportunity and Size In 1981 there were approximately 18 million cable subscribers in the US, constituting about 23% of households with TV sets. The pace of cable construction was accelerating rapidly and industry analysts expected the wiring of larger markets to generate 26 million new cable subscribers by 1990.12 Landmark believed channel upgrades along with cable construction would create the opportunity for a weather channel to gain wide distribution in a rapidly growing cable marketplace. Although traditional twelvechannel cable systems already had a channel reserved for weather, Landmark believed that a superior product could easily replace existing weather channels.13 Projections for adoption, audience ratings, advertising, and revenue made during Landmark’s due diligence were largely based on best-guess estimates and approximations. Based on surveys conducted with cable companies, Landmark concluded that most cable operators who already carried local textbased weather channels would replace them with The Weather Channel and that new cable systems and systems that were adding channel capacity, would rapidly adopt a free weather channel.14 Landmark did not expect to charge cable operators a fee to carry The Weather Channel, the company was completely dependent on advertising for all of its revenue. Gaining wide distribution and adoption would be critical to securing advertising. The US television advertising market was enormous at an 11 Frank Batten and Jeffrey Cruikshank The Weather Channel: The Improbable Rise of a Media Phenomenon (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 2002) 12 Ibid 13 Ibid 14 Ibid estimated $11.3 billion and growing. Landmark determined that a national weather channel would only have to take about 0.1 percent of that market to break even. Landmark believed it would be able to capture at least 2 to 3 percent share of cable advertising, assuming optimistic projections about the growth of advertising revenues on cable.15 These assumptions were predicated on The Weather Channel’s ability to gain a Neilson rating, the key measure advertisers used to judge a television program’s appeal and consequently the attractiveness for advertisers. In order to garner a Neilson rating, a station needed to reach at least 15 million subscribers. Landmark expected to receive a Nielson rating slightly below the rating then claimed by CNN.16 Although the most attractive advertisersupported networks—ESPN, CNN and USA—were also reaping revenues from fees charged to cable operators, Landmark believed The Weather Channel would still be attractive from a profit standpoint. Landmark projected that programming costs would be low because it would not be required to pay for the rights to sports events or movies. All in, Landmark estimated a loss of $924,000 for the first year of operation and a profit of just over $2.7 million for the second year. 17 The Innovation Ecosystem The rise of The Weather Channel was predicated on six critical elements. Each element of the ecosystem was equally important. Without a single piece, success would not be possible. 15 Frank Batten “Out of the Blue and into the Black,” Harvard Business Review 2002 Frank Batten and Jeffrey Cruikshank The Weather Channel: The Improbable Rise of a Media Phenomenon (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 2002) 17 Ibid 16 Satellite Transponder In order to deliver The Weather Channel to subscribers across the nation, Landmark needed to acquire a lease on a satellite transponder. While finding available transponders was not a difficult task, getting a transponder lease on the right satellite was. With substantial investment costs in signal receiving technology (satellite dishes) for cable operators and different dishes needed to receive signals from different satellites, Landmark knew it was essential to secure a lease on a satellite with other highly demanded program providers. Landmark wanted a lease on RCA’s Satcom 1 satellite alongside HBO and the Turner networks, which reached 95% of cable households in the US.18 Upon initial inquiry, all of the satellites 24 transponders were under contract. In June of 1981, a transponder lease became available on Satcom 1 and was open for bidding. Though Landmark was bidding against companies with much deeper pockets, it was able to make bigger and riskier bids as a private company than many of its public competitors, which were subject to shareholder scrutiny. Landmark’s bold bidding ultimately secured its lease on Satcom 1 and satisfied one critical component of its path to launching The Weather Channel. WeatherSTAR technology Landmark believed that cable operators would have no interest in a 24 hour weather station if it did not provide local weather information to subscribers. The company had to find a way to broadcast localized text information around the nationally focused video programing. Local cable weather stations already existed that would switch between text display and video images. Landmark’s ability to provide a value added product to customers rested in its capacity to do both simultaneously to a national audience. Landmark used internal talent and hired additional resources to tackle much of its technological challenge. Its internal team ultimately developed a way to intersperse video and text with the broadcast signal so that the two elements could be displayed concurrently. They also developed the capability to attach tags to the signal so that the appropriate local weather information would be picked up by the proper cable operators and delivered accurately to the right subscribers. While much of the broadcast signal technology was developed internally, Landmark partnered with Salt Lake City based Compuvid to develop the device that would ultimately broadcast the unique signal. Once again, Landmark’s flexibility as a private company afforded it the ability to internalize much of the technological innovation risk by tapping its own employee talent pool, hiring the necessary additional people and providing its team its requisite capital. With the ability to broadcast across the nation and the technology to provide its innovative weather programming, Landmark was edging towards launch. 18 Frank Batten and Jeffrey Cruikshank The Weather Channel: The Improbable Rise of a Media Phenomenon (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 2002) Weather Data The Weather Channel would need detailed weather data, which Landmark did not have. The US government’s National Weather Service (NWS) with 500 weather stations across the country, was the obvious choice for supplying weather information. Throughout the 1970s and early ‘80s, the NWS was facing major potential funding cuts as members of government looked to eliminate unnecessary public spending. In negotiations with NWS, Landmark highlighted its ability to elevate the agency’s importance by guaranteeing to cite its data throughout its programming and by distributing its valuable severe weather watches and warnings to subscribers. In return, Landmark needed the agency to standardize its weather data. The threatened abolition of the NWS in conjunction with Landmark’s commitment to breathe new life into the agency, however, was enough to push the agency to agree and complete the necessary standardization quickly. Landmark not only needed weather data, but also it needed help managing all of the data. The company looked to Weather Services International (WSI) for help. WSI was a Massachusetts based firm that specialized in taking large amounts of information, storing it in databases and providing it to customers in a manageable form. What it needed most from WSI was a way to tag all of the information so that its Weather STAR technology could process it properly and deliver it to local audiences. Given its core competencies, WSI easily met Landmark’s needs. With the necessary technology and data, Landmark had satisfied two major needs within its ecosystem. Getting its product into customers’ homes and making money had yet to be accomplished. Cable Operators Cable operators were critical to distributing The Weather Channel to customers. While Landmark was fortunate to have an initial audience from its TeleCable business, the Telecable subscriber base was not enough to bring in advertising dollars. Its lease on Satcom 1 provided additional ease into US households, as most cable operators had the necessary dish to receive its satellite signal. Landmark pushed a hard sell to cable operators, not demanding a fee to distribute their programing like other program providers and detailing the utility of their product citing that “The Weather Channel will save lives.”19 However, space for cable programming was in high demand and Landmark’s weather channel was competing against programmers such as CNN, Nickelodeon and ESPN, which delivered more tested and traditional television programming. Despite its challenges, Landmark was able to secure contracts with 19 Frank Batten and Jeffrey Cruikshank The Weather Channel: The Improbable Rise of a Media Phenomenon (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 2002) seven of the top 13 cable operators. By its launch in 1982, The Weather Channel had 4.2 million subscribers, a launch record for cable operators. 20 While attracting cable operators to distribute The Weather Channel to subscribers was essential, cable operators generated no revenue for Landmark to sustain the channel. In the beginning, Landmark was relying on advertising as its sole source of revenue. Advertisers Advertising on cable networks in 1980 was worth $45 million compared to $15.6 billion in newspapers and $11.3 billion in traditional broadcast television. The cable advertising business, however, was expected to grow to $2.2 billion in 1990. It was this growing market that Landmark hoped to profit from its weather channel.21 Though Landmark had more than 4 million subscribers to The Weather Channel at its launch, it was far from the 15 million subscribers it needed for its Neilson rating and access to the most lucrative advertising dollars.22 Nonetheless, Landmark pursued an aggressive advertising strategy looking for advertisers whose products fit well with The Weather Channel’s programing such as cough medicines, tires and other travel related items. In addition, Landmark looked to the same technology that delivered text based local weather forecasts to deliver text based local advertising. TWC partnered with national companies to target their advertisements to specific markets. These localized commercials were unique to The Weather Channel and provided critical revenue to The Weather Channel in its infancy as it gained subscribers and worked towards major advertising contracts. Customers With the rise of 24 hour news stations such as CNN and Headline News, a similar station devoted solely to weather seemed reasonable. Given the impact of weather on people’s lives, viewers regularly tuned into to weather broadcasts. Prior to the launch of The Weather Channel, weather related programming accounted for merely 15 minutes of daily broadcasting, typically just quick segments on traditional news programs. Alternatives to a potential weather channel were basic. Many cable systems carried 24 hour weather stations that provided a text image interspersed with low quality images of temperature and wind dials. The potential to tell a 24 hour weather story with news like anchors and local detail was very valuable to potential customers. At the time, a survey conducted by Neilson indicated that nearly half of the survey 20 Frank Batten and Jeffrey Cruikshank The Weather Channel: The Improbable Rise of a Media Phenomenon (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 2002) 21 Ibid 22 Frank Batten “Out of the Blue and into the Black,” Harvard Business Review 2002 population had significant interest in a 24 hour weather channel. 23 Risk Assessment of The Weather Channel’s Ecosystem From the start of The Weather Channel venture, Landmark was consistent in its strategy to internalize many of the technological risks it faced and continued to find ways to mitigate the risks it encountered in its ecosystem of interconnected players. In assessing the risks, Landmark knew it had to allocate internal resources to the project and rely heavily on its in-house human capital to develop several key technologies that were essential to the launch of The Weather Channel. While this forced Landmark to take on much of the initiative risk, it was able to significantly lower its dependence on complementary innovators and did not face substantial co-innovation risk. With the exception of the National Weather Service, which had a strong incentive to move quickly to standardize its data and did not require significant technological innovation, Landmark’s internalization of much of the innovation helped ensure its ability to be a first mover in the space. In addition to initiative risk, the successful launch of The Weather Channel required overcoming substantial adoption risk. To sustain The Weather Channel, cable operators needed to pick up the channel and offer it to its customers. Only after customers began watching the channel could Landmark expect to attract advertisers and the associated revenue. Table 1 below details the risks faced by Landmark and the steps they took to mitigate the risk in order to successfully launch its product. 23 Frank Batten and Jeffrey Cruikshank The Weather Channel: The Improbable Rise of a Media Phenomenon (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 2002) Table 1 Unrealistic Expectations: The Weather Channel Struggles for Survival Following the launch of The Weather Channel, Landmark struggled to attract the large number of new subscribers it needed to meet Neilson’s 15 million subscriber hurdle for its all-important rating. The company was adding 125,000 new subscribers per week, but at that rate, it would take the company more than a year and half to build a subscriber base of 15 million households. In addition, it was costing Landmark more in capital investments to bring new subscriptions than it was earning in advertising revenue.24 These initial struggles were largely due to failed due diligence expectations for both subscribership and advertising revenue that The Weather Channel’s model was predicated on. While cable television was in its relative infancy and Landmark had little data to pull from to make projections, assuming that it could achieve 15 million subscribers when the whole cable market was just 18 million subscribers was unrealistic. Coupled with the lower than expected advertising revenue were higher than expected programming costs. During due diligence, Landmark projected that costs to acquire necessary weather information and data for its programming would be low given that there were no related licensing fees that were characteristically high for other program providers such as ESPN for sports and HBO for movies. However, the cost to process and distribute its weather data as well as provide quality weather programming was more costly than Landmark expected. Other major program providers such as ESPN and CNN were losing significant amounts of money in the early 1980s as well. Operating expenses to develop and broadcast programming was greater than the revenue from advertising and paltry subscription fees. The Wall Street Journal reported that ESPN was losing $20 million a year in the early ‘80s.25 Without a broad base of cable subscribers and the major advertising contracts, Landmark didn’t believe it could keep The Weather Channel afloat. As the company considered shutting down operations or finding a buyer, the dynamics within its ecosystem changed. An Evolution in the Ecosystem: Cable Operators Need Programming As cable operators moved into major urban areas to grow their subscription base, their value proposition also had to change. Previously, the greatest benefit of cable television to consumers was a clear and consistent picture quality. While programing was important, it wasn’t nearly as critical to cable’s rural success as it would be to its urban success. In urban areas, proximity to microwave based broadcast signals provided viewers with a high quality video image. Additionally, access to a large number of viewers ensured advertising revenue and, therefore, higher quality programing. For cable to compete in this market, it would have to win on programing. 24 Frank Batten “Out of the Blue and into the Black,” Harvard Business Review 2002 Ibid. 25 At the same time, cable system technology advanced to allow a broader range of stations, 35-60 stations versus the traditional 12 stations.26 However, many of the early program providers were terminating their services because of unfavorable profit potential in cable programing. The need for cable operators to fill their channel capacity and provide customers with a diverse menu of programs to gain traction in the urban areas incentivized cable operators to support program providers. The Weather Channel had yet to shut down operations when cable operators began offering to pay Landmark to broadcast The Weather Channel to subscribers. By the end of 1983, fifteen of the largest cable companies had signed three year deals with Landmark for The Weather Channel.27 Revenue from cable operators along with millions of new subscribers and major advertising contracts set Landmark and The Weather Channel on a stable path to success. Leading the Ecosystem Table 2 highlights that Landmark was clearly the leader of its innovation ecosystem. It was capable of generating the surplus to align the necessary actors and overcome its technological and information needs to launch The Weather Channel. Based on its expectations and need to gain substaintial subscribers for sucess, however, The Weather Channel ultimatly was subject to the development of the larger cable ecosystem, which it was not poised to lead. Had landmark been more attuned to challenges in the broader cable industry, it could have waited for the necessary development of the cable ecoystsem to lauch its product or taken a minimal vaible footrint approach that would have been less costly and more sustainable given its niche advertising possibilities. With the poor quality of 24 hour weather rivals, a simply superior product rather than a vastly superior product could have allowed The Weather Channel to develop a proftable foothold in the cable industry through which it could have further developed its product once the cable ecosystem was advanced enough to support it with major advertising revenue. 26 Frank Batten and Jeffrey Cruikshank The Weather Channel: The Improbable Rise of a Media Phenomenon (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 2002) 27 Ibid. Table 2 Carryover Into New Businesses Throughout the ‘80s and ‘90s, The Weather Channel grew its businesses to become the most trusted name in weather. Landmark’s leadership was notorious for spotting opportunity and during the internet boom in the 1990’s, Landmark was early to the internet game claiming the domain name “weather.com”. The Weather Channel on the internet brought a new medium and a new type of conversation to consumers. With time and space limits on The Weather Channel, weather.com gave consumers additional relevant information such as airport delays, climatology databases, hour-by-hour forecasts, ten-day forecasts, and thousands of current conditions and forecasts for international cities.28 Just as it did on TV, The Weather Channel aimed to differentiate its web site from poor quality 28 Frank Batten and Jeffrey Cruikshank The Weather Channel: The Improbable Rise of a Media Phenomenon (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 2002) competitors using the same public data from NWS. Weather.com focused on visual design and constantly updated, detailed information as their differentiating factor, which required a considerable investment in technology. In the same way that NWS gained from its brand credibility in the early days of The Weather Channel, The Weather Channel’s own brand and consumer following become critical to its success as it reached into related businesses. It was brand trust and consumer loyalty that carried over from The Weather Channel and made its new properties in television, radio, and business-to-business weather services, as well as digital properties such as weather.com and wireless platforms successes. [1] First Mover Advantage: The Weather Channel and weather.com When Landmark Communications decided to move forward with The Weather Channel venture, Frank Batten realized that he had to move quickly in order to be the first high-quality 24/7 weather channel. The idea for this type of station was well known and there certainly wouldn’t be room for two weather channels. With weather, there is little room for editorializing like with news. Additionally, all weather stations would be based on the same underlying weather data from the NWS. With the advent of national broadcasting, competition was heating up among program providers as they battled for slots on satellites and for cable operator’s channels. Given the initial scarcity of distribution channels for program providers, being the first to market was critical to the success of The Weather Channel. Gaining the first mover advantage had always been a critical part of Landmark Communications strategy. As a newspaper publisher, Landmark understood that in many markets, there was only room for one widely circulated newspaper. In the cable operating business, local governments award franchises to a single cable operator. Given the significant investment necessary to build a cable system from the ground up and the undifferentiated product offering of television cable – services, being first to the party in a given area was critical for Telecable’s success.29 While The Weather Channel was one of the first to make weather data available to consumers directly over the internet, being the first to the internet was not key to the success of weather.com. The Weather Channel’s trusted brand and ability to provide its customers with a more detailed as well as a differentiated product were these keys to its online success. [1] The Weather Channel Backgrounder, http://press.weather.com/company.asp Subramanian Rangan and Ron Adner, “Profits and the Internet: Seven Misconceptions” MIT Sloan Review (Summer 2001) 29 Conclusion Frank Batten’s instance on developing new ideas was certainly the foundation of The Weather Channel’s success. Batten and his team were flawless at envisioning the value of its weather channel product and managing relationships with partners to bring it to market. Where Landmark failed was in its expectation of the cost of operating its channel, estimating the size of the cable industry and generating the necessary advertising revenues to turn a profit. What ultimately saved The Weather Channel from extinction was the broader cable ecosystem’s need for high-quality programing. The increased demand for Landmark’s product and revenue from subscription fees that resulted from a change in the cable operator ecosystem sustained and helped grow The Weather Channel into the lucrative success that it remains today.