Lecture Outlines

Chapter 17

Physics, 3rd Edition

James S. Walker

© 2007 Pearson Prentice Hall

This work is protected by United States copyright laws and is provided solely for

the use of instructors in teaching their courses and assessing student learning.

Dissemination or sale of any part of this work (including on the World Wide Web)

will destroy the integrity of the work and is not permitted. The work and materials

from it should never be made available to students except by instructors using

the accompanying text in their classes. All recipients of this work are expected to

abide by these restrictions and to honor the intended pedagogical purposes and

the needs of other instructors who rely on these materials.

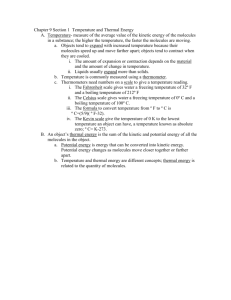

Chapter 17

Phases and Phase Changes

Units of Chapter 17

• Ideal Gases

• Kinetic Theory

• Solids and Elastic Deformation

• Phase Equilibrium and Evaporation

• Latent Heats

• Phase Changes and Energy

Conservation

17-1 Ideal Gases

Gases are the easiest state of matter to

describe, as all ideal gases exhibit similar

behavior.

An ideal gas is one that is thin enough, and far

away enough from condensing, that the

interactions between molecules can be ignored.

17-1 Ideal Gases

If the volume of an ideal

gas is held constant, we

find that the pressure

increases with

temperature:

17-1 Ideal Gases

If the volume and

temperature are kept

constant, but more gas is

added (such as in

inflating a tire or

basketball), the pressure

will increase:

17-1 Ideal Gases

Finally, if the

temperature is constant

and the volume

decreases, the pressure

increases:

17-1 Ideal Gases

Combining all three observations, we write

where k is called the Boltzmann constant:

17-1 Ideal Gases

Rearranging gives us the equation of state for

an ideal gas:

Instead of counting molecules, we can count

moles. A mole is the amount of a substance

that contains as many elementary entities as

there are atoms in 12 g of carbon-12.

17-1 Ideal Gases

Experimentally, the number of entities (atoms

or molecules) in a mole is given by

Avogadro’s number:

Therefore, n moles of gas will

contain

molecules.

17-1 Ideal Gases

Avogadro’s number and the Boltzmann constant

can be combined to form the universal gas

constant and an alternative equation of state:

17-1 Ideal Gases

The atomic or molecular mass of a substance

is the mass, in grams, of one mole of that

substance. For example,

Helium:

Copper:

Furthermore, the mass of an individual atom

is given by the atomic mass divided by

Avogadro’s number:

17-1 Ideal Gases

Boyle’s law, which is

consistent with the ideal

gas law, says that the

pressure varies inversely

with volume. These curves

of constant temperature are

called isotherms.

17-1 Ideal Gases

Charles’s law, also

consistent with the

ideal gas law, says

that the volume of a

gas increases with

temperature if the

pressure is constant.

17-1 Ideal Gases

In this photograph,

the balloon was

inflated at room

temperature and

cooled with liquid

nitrogen. The

decrease in volume

of the air in the

balloon is obvious.

17-2 Kinetic Theory

The kinetic theory relates microscopic

quantities (position, velocity) to macroscopic

ones (pressure, temperature). Assumptions:

• N identical molecules of mass m are inside a

container of volume V; each acts as a point

particle.

• Molecules move randomly and always obey

Newton’s laws.

• Collisions with other molecules and with the

walls are elastic.

17-2 Kinetic Theory

Pressure is the result

of collisions between

the gas molecules

and the walls of the

container.

It depends on the mass and speed of the

molecules, and on the container size:

17-2 Kinetic Theory

Not all molecules in a gas will have the same

speed; their speeds are represented by the

Maxwell distribution, and depend on the

temperature and mass of the molecules.

17-2 Kinetic Theory

We replace the speed in the previous

expression for pressure with the average

speed:

Including the other two directions,

Therefore, the pressure in a gas is

proportional to the average kinetic energy of

its molecules.

17-2 Kinetic Theory

Comparing this expression with the ideal gas

law allows us to relate average kinetic energy

and temperature:

The square root of

mean square (rms) speed.

is called the root

17-2 Kinetic Theory

Solving for the rms speed gives:

17-2 Kinetic Theory

The rms speed is slightly greater than the

most probable speed and the average speed.

17-2 Kinetic Theory

The internal energy of an ideal gas is the sum

of the kinetic energies of all its molecules. In

the case where each molecule consists of a

single atom, this may be written:

17-3 Solids and Elastic Deformation

Solids have definite shapes (unlike fluids), but

they can be deformed. Pulling on opposite

ends of a rod can cause it to stretch:

17-3 Solids and Elastic Deformation

The amount of

stretching will depend

on the force; Y is

Young’s modulus and is

a property of the

material:

17-3 Solids and Elastic Deformation

Another type of deformation is called a shear

deformation, where opposite sides of the

object are pulled laterally in opposite

directions.

17-3 Solids and Elastic Deformation

As expected, the deformation is proportional

to the force. S is the shear modulus.

17-3 Solids and Elastic Deformation

Finally, if a solid is uniformly compressed, it

will shrink.

17-3 Solids and Elastic Deformation

Here, the proportionality constant, B, is called

the bulk modulus.

17-3 Solids and Elastic Deformation

The applied force per

unit area is called the

stress, and the resulting

deformation is the

strain. They are

proportional to each

other until the stress

becomes too large;

permanent deformation

will then occur.

17-4 Phase Equilibrium and Evaporation

If a liquid is put into a sealed container so that

there is a vacuum above it, some of the

molecules in the liquid will vaporize. Once a

sufficient number have done so, some will

begin to condense back into the liquid.

Equilibrium is reached when the numbers

remain constant.

17-4 Phase Equilibrium and Evaporation

The pressure of the gas when it is in

equilibrium with the liquid is called the

equilibrium vapor pressure, and will depend

on the temperature.

17-4 Phase Equilibrium and Evaporation

The vaporization curve determines the boiling

point of a liquid:

A liquid boils at the temperature at which its

vapor pressure equals the external pressure.

This explains why water boils at a lower

temperature at lower pressure – and why you

should never insist on a “3-minute egg” in

Denver!

17-4 Phase Equilibrium and Evaporation

This curve can be expanded. When the liquid

reaches the critical point, there is no longer a

distinction between liquid and gas; there is

only a “fluid” phase.

17-4 Phase Equilibrium and Evaporation

The fusion curve is the

boundary between the solid

and liquid phases; along that

curve they exist in

equilibrium with each other.

Almost all materials have a

fusion curve that resembles

(a); water, due to its unusual

properties near the freezing

point, follows (b).

17-4 Phase Equilibrium and Evaporation

Finally, the sublimation curve marks the

boundary between the solid and gas phases.

The triple point is where all three phases are in

equilibrium. This is shown on the phase

diagram below.

17-4 Phase Equilibrium and Evaporation

A liquid in a closed container will come to

equilibrium with its vapor. However, an open

liquid will not, as its vapor keeps escaping – it

will continue to vaporize without reaching

equilibrium. As the molecules that escape

from the liquid are the higher-energy ones, this

has the effect of cooling the liquid. This is why

sweating cools us off.

17-4 Phase Equilibrium and Evaporation

If we look at the Maxwell speed distributions for

water at different temperatures, we see that there

is not much difference between the 30° C curve

and the 100° C curve. This means that, if 100° C

water molecules can escape, many 30° C

molecules will also.

17-4 Phase Equilibrium and Evaporation

This same evaporation process can cause a

planet to lose its atmosphere – some molecules

will have speeds exceeding the escape velocity.

The evaporation process will be faster for

lighter molecules and for less massive planets.

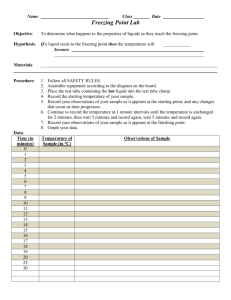

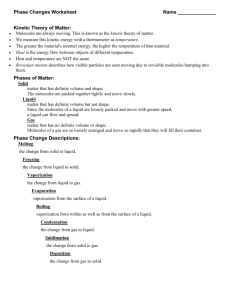

17-5 Latent Heats

When two phases coexist, the temperature

remains the same even if a small amount of

heat is added. Instead of raising the

temperature, the heat goes into changing the

phase of the material – melting ice, for

example.

17-5 Latent Heats

The heat required to convert from one phase to

another is called the latent heat.

The latent heat, L, is the heat that must be

added to or removed from one kilogram of a

substance to convert it from one phase to

another. During the conversion process, the

temperature of the system remains constant.

17-5 Latent Heats

The latent heat of fusion is the heat needed to

go from solid to liquid; the latent heat of

vaporization from liquid to gas.

17-6 Phase Changes and Energy

Conservation

Solving problems involving phase changes is

similar to solving problems involving heat

transfer, except that the latent heat must be

included as well.

Summary of Chapter 17

• An ideal gas is one in which interactions

between molecules are ignored.

• Equation of state for an ideal gas:

• Boltzmann’s constant:

• Universal gas constant:

• Equation of state again:

• Number of molecules in a mole is Avogadro’s

number:

Summary of Chapter 17

• Molecular mass:

• Boyle’s law:

• Charles’s law:

• Kinetic theory: gas consists of large

number of pointlike molecules

• Pressure is a result of molecular collisions

with container walls

Summary of Chapter 17

• Molecules have a range of speeds, given by

the Maxwell distribution

• Relation of kinetic energy to temperature:

• Relation of rms speed to temperature:

Summary of Chapter 17

• Internal energy of monatomic gas:

• Force required to change the length of a

solid:

• Force required to deform a solid:

Summary of Chapter 17

• Pressure required to change the volume of a

solid:

• Applied force per area: stress

• Resulting deformation: strain

• Deformation is elastic if object returns to its

original size and shape when stress is

removed

Summary of Chapter 17

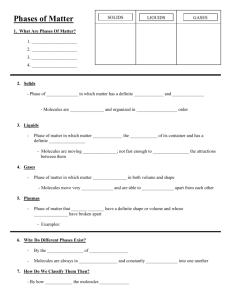

• Most common phases of matter: solid, liquid,

gas

• When phases are in equilibrium, the number

of molecules in each is constant

• Evaporation occurs when molecules in liquid

move fast enough to escape into gas phase

• Latent heat: amount of heat required to

transform from one phase to another

• Latent heat of fusion: melting or freezing

Summary of Chapter 17

• Latent heat of vaporization: vaporizing or

condensing

• Latent heat of sublimation: sublimation or

condensation directly between gas and solid

phases

• When heat is exchanged within a system

isolated from its surroundings, the energy of

the system is conserved