detailed 8 pg doc

advertisement

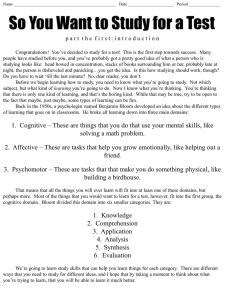

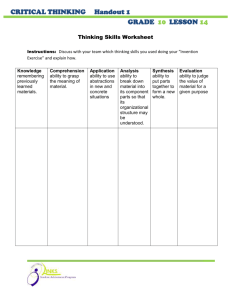

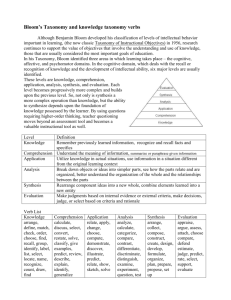

Name _________________________________________________ Date ______________________ Period _______________ So You Want to Study for a Test part the first:introduction Congratulations! You’ve decided to study for a test! This is the first step towards success. Many people have studied before you, and you’ve probably got a pretty good idea of what a person who is studying looks like: head bowed in concentration, stacks of books surrounding him or her, probably late at night, the person is disheveled and panicking…you get the idea. Is this how studying should work, though? Do you have to wait ‘till the last minute? No, dear reader, you don’t. Before we begin learning how to study, you need to know what you’re going to study. Not which subject, but what kind of learning you’re going to do. Now I know what you’re thinking. You’re thinking that there is only one kind of learning, and that’s the boring kind. While that may be true, try to be open to the fact that maybe, just maybe, some types of learning can be fun. Back in the 1950s, a psychologist named Benjamin Bloom developed an idea about the different types of learning that goes on in classrooms. He broke all learning down into three main domains: 1. Cognitive – These are things that you do that use your mental skills, like solving a math problem. 2. Affective – These are tasks that help you grow emotionally, like helping out a friend. 3. Psychomotor – These are tasks that that make you do something physical, like building a birdhouse. That means that all the things you will ever learn will fit into at least one of these domains, but perhaps more. Most of the things that you would want to learn for a test, however, fit into the first group, the cognitive domain. Bloom divided this domain into six smaller categories. They are: 1. Knowledge 2. Comprehension 3. Application 4. Analysis 5. Synthesis 6. Evaluation We’re going to learn study skills that can help you learn things for each category. There are different ways that you need to study for different ideas, and I hope that by taking a moment to think about what you’re trying to learn, that you will be able to learn it much better. Name _________________________________________________ Date ______________________ Period _______________ So You Want to Study for a Test part two:knowledge This first part will teach you about knowledge questions. A knowledge question is something that you simply know or do not know. Some examples are below: 1. “What is the final electron acceptor in cellular respiration?” 2. “Who was the first president of the United States of America?” 3. “Where is the largest tree in the world located?” You see, these questions are not things that you can figure out on scrap paper, or ones that you can think about for a while and figure out; you really just have to have the knowledge in your head. Many times, these questions begin with one of the question words (who, what, where, when, why or how), and they make excellent multiple-choice questions. These are questions that you shouldn’t spend too much time on if you’re confused, because if you don’t know it, you just don’t know it. In order to study for these types of questions, drill and practice are necessary. While this type of learning concerns mostly facts that you simply have to know, there are techniques that can help you remember things better. 1. Make a list of main concepts in order of importance to help you remember. Often, when facts are put into a context (such as rank-ordering), they are much easier to remember, because they’re not just a “bunch” of facts, but a nice, neat list. Example: President, Vice President, Speaker of the House, President Pro Tempore of the Senate, Secretary of State. 2. Make flash cards with pictures on them. The pictures do not have to be related to the topic, but they have to be something with which you may associate the topic. Example: Put a picture of a cat on a card about caterpillars, to help you associate the ideas. 3. Make pictograms on paper or on flash cards. Clever little phrases or pictures can help you remember what something is or what it does. Example: A picture of a house and a burger with a purse can help you remember that the House of Burgesses had the “power of the purse” in colonial America. 4. Make mnemonic devices. These are any rhymes or devices that are helpful to the memory. Example: Make an acronym using the first letters of the major taxa to form a phrase like “King Phillip Came Over For Grape Soda” (Kingdom, Phylum, Class, Order, Family, Genus, Species). 5. Write out each individual idea or word that you need to remember on a note card, then lay out the cards in groups on the ground according to what they’re about. The groups will help you associate terms, and make them easier to remember. Example: Group together “ATP, mitochondrion, inner membrane, matrix and NADH” in cluster of words about cellular respiration. Name _________________________________________________ Date ______________________ Period _______________ So You Want to Study for a Test part three:comprehension This particular section will teach you about comprehension questions. A comprehension question is designed to make sure that you understand the basis behind an idea, in addition to knowing what it is. It is one step above a knowledge question. Some examples are below: 1. “Explain the purpose of voting in your own words.” 2. Why is smoking not a good idea? 3. What kind of person was Goldilocks? Again, these are not questions that you could figure out on scrap paper, but they are a little more complex than just knowing or not knowing something. To know what kind of person Goldilocks was, you would need to understand what happened in the story and be able to explain it to someone else. These are questions that you shouldn’t spend too much time trying to figure out, but they are often worth guessing on. Chances are that you know something about the subject, and partial credit on tests can often be allowed. These questions are best studied for with a partner or a group. This way, you can build off the ideas of others, and find other ways to phrase difficult ideas. 1. Make a flow chart. This can help you put events or ideas in order, and separating ideas visually is a good way to make them stick in your head. Remembering what happens before or after something else can often help you figure out why or where it was happening. Example: Make a flow chart of the events in Romeo and Juliet, so you know who died when. Remembering the order of events can often make answering comprehension questions easier. 2. Write a précis. A précis is a short summary, much like an abstract, that gives just the bare facts of a situation. The physical act of writing can help you remember facts more easily by involving another part of your brain. Example: Write one paragraph on human circulation. You can re-read it at any point to refresh your memory, and it is a great way to keep the big picture in your mind, so you don’t get lost in the details. 3. Make a Mad Lib®. By making a story with blanks in it, you can force yourself or others to remember specific events or details. They’re fun, too! Example: “One day, a _____________ was making some ATP, when his _________ membrane collapsed, and the protons could no longer form a ___________.” 4. Make a song, play or small skit with a group of friends. After you perform the skit or song, you will be able to associate one of your friends with a concept or other character. Example: Turn your room at home into a cell, assigning your little brother to be the lysosome. 5. Make a landscape. A picture is worth a thousand words! Example: Draw a landscape with monsters and heroes to represent the events in Beowulf. Name _________________________________________________ Date ______________________ Period _______________ So You Want to Study for a Test part four:application This section will introduce you to application questions. Application questions are one step above comprehension questions, but they really aren’t any harder. An application question simply asks you to use a concept that you learned with one idea, and use it with another. Some examples are below: 1. “How are badgers like people?” 2. “How can you use soap to clean an elephant?” 3. “Why do birds sing in the morning?” These types of questions require you to take knowledge or information that you know from one situation, and then use them in another situation. For example, if you wanted to know how to wash an elephant with soap, you would have to know how to use soap. You could probably figure out what to do, even if you haven’t ever washed an elephant, because you know how to use soap to wash things. These questions are usually worth spending a little time on, even if you’re not completely sure of the answer. This is because you can at least put down what you know about the situation (washing), even if you don’t know all of it (how to wash an elephant). 1. Play a pretend game. Pretend that you can no longer use a skill for what it is intended, and instead, try to figure out how else you can use it. This helps you apply ideas from one situation to another, new one. Example: Pretend that you need to use English grammar in a made-up language. Where would commas go? What about capital letters and quotation marks? 2. Make a chart. You can use a graph or Venn diagram to show the similarities and differences between two sets of ideas. Example: Make a chart, with one side showing how you can use elephant-washing skills on an elephant, and with the other side showing how you might apply those skills to washing a car. 3. Write an instruction manual for your topic. By writing down what ideas or skills you need to perform a task or complete an assignment, you can often help yourself understand it more. Maybe your manual could teach others, too! Example: Write an instruction manual on how to get a protein inside a cell against its concentration gradient. Share it when you’re done so others can benefit, too! 4. Write out your ideas in equation form. By simplifying your ideas down to an equation, you can worry less about the actual topic and more about how that topics works. Example: Write an equation for how to construct an essay. Something like “Essay = introduction + body paragraphs + summary + conclusion.” If it’s already a mathy-type class (like math…or science), try reversing the process and writing out your equation in words! 5. Think of another planet or a civilization. By projecting your idea onto another, distant place, you can separate the concept that you’re trying to apply from the actual facts. Example: How could people live on mars? What would we need to live there? Name _________________________________________________ Date ______________________ Period _______________ So You Want to Study for a Test part five: analysis This section will introduce you to analysis questions. Analysis questions are one step above application questions, but they really aren’t any more complex. An analysis question asks you to take what you know about a subject, and see how well it was applied to another. Some examples are below: 1. “What was the main theme of the book?” 2. “How is Shakespeare similar to Lady Gaga?” 3. “What are some of the motives for the murder?” These types of questions require you to use what you know about the world and come up with an opinion or criticism of the topic at hand. You might not know much about the topic, but you can certainly try and see if you can form an opinion of it. For example, if you are asked to write an essay about politics, you could say that the republicans and democrats are not all that different on many issues, but on some, key ones, they have very strong opinions. You’ve got to take what you know, turn it about in your head, and come up with some critique or summary of the situation. These questions are usually worth spending a little time on, and they’re usually longer, essay-type questions. Make sure you read the question carefully, so you know what “lens” to look through when you’re creating your analysis. 1. Make a pretend sportscast of the idea. By forcing yourself to summarize and present information on the subject to an audience, you’ll automatically have to analyze it. Example: “It’s the bottom of the ninth, and Romeo is still alive…no…wait, he’s kissed Juliet’s lips…he’s getting some poison, what will his next move be? It looks like he doesn’t want to live without her!” 2. Write a newspaper review. Even something like a math problem can be reviewed. Point out what was hard, what was easy, and what didn’t make sense. This can help you identify strengths and weaknesses. Example: “This math problem was easy. FOILing is simple for me, so I didn’t have much trouble with it. I don’t like having to find the GCF, though.” 3. Make a puzzle or game. This will help you figure out which pieces need to go where. Example: Make a puzzle with each step of cellular respiration on a separate piece. Then you can hook them together and analyze which order of steps makes sense to you. 4. Make a flow chart to show how one item connects to another. This can help you envision a complex idea. Example: Show how the story line of Hamlet goes along with a chart. 5. Make a commercial to sell a product featuring your idea. By identifying what is important about a particular idea, you can easily figure out what to study first. Example: Try and sell glucose to cells. Tell them how rich in energy the bonds are, and how easy it is to break glucose down into two pyruvates. What a great way to make ATP! But wait! There’s More! Name _________________________________________________ Date ______________________ Period _______________ So You Want to Study for a Test part six: synthesis This section will introduce you to synthesis questions. Synthesis questions are one step above analysis questions, and they tend to be quite a bit more complex. A synthesis question asks you to take two separate bits of knowledge and fit them together in a way that makes sense and forms some new bit of knowledge. Some examples are below: 1. “What would happen if you added baking soda to vinegar?” 2. “How can you build a machine to make scrambled eggs?” 3. “What are some different ways to make pancakes?” These types of questions require you to use what you know about two or more topics and smash that knowledge together. Synthesis questions are very important, because often times we learn a certain fact in one context, but need to use it with several other facts in a different context. As an example, just knowing how a hammer works isn’t very useful unless you can figure out how it works together with nails, your hand, lumber, etc. Synthesis questions can appear difficult and are often a bit more complex than some of the other types of questions, but once you realize what bits of information you’re being asked to combine, the question can become much more straightforward. These questions are usually worth spending a little time on, even if it’s just to figure out what to (or three or four or…) things you are being asked to combine. Even if you can’t get the complete answer correct, just knowing what two areas of knowledge you’re dealing with can get you partial credit. 1. Make a physical diagram of the problem. By drawing or writing out what you need to know, you can fill in what you already have, then work on what you need to find out. Example: Draw out a plan of a house that you’re working on to figure out where the best places for the windows, doors and light fixtures should be. Label wattages, temperatures, etc. 2. Make a list of directions for someone else to follow. By enumerating the steps that you have to take to solve a problem or perform a task, you’re likely to see the individual bits of knowledge that are needed. Example: Write a set of directions for using a micropipettor. Include all the steps so that even a person who has never used one before would be able to do so. 3. Put your task or problem to music. By making the words that you’re working with memorable and synthesizing them with music, your brain is more likely to understand them. Use a well-known melody or make up your own. Either way, you’re synthesizing. Example: “Do you know the wingnut man, the wingnut man, the wingnut man….” 4. Design a CD insert or magazine cover about your subject. By synthesizing it with a new idea or format, you can come to understand it in a different light. Example: Make a CD insert that describes the songs in the life of Charles Darwin. You might include such hits as “I naturally select you!” or “Why don’t you evolve an opposable thumb?” Putting two (perhaps silly!) ideas together can actually help your brain remember them both much better. Name _________________________________________________ Date ______________________ Period _______________ So You Want to Study for a Test part seven: evaluation This section will introduce you to evaluation questions. Evaluation questions are one step above synthesis questions, but that doesn’t mean that they’re anymore complex, just that they might take a little longer to answer. An evaluation question asks you to make a judgment call about an ideabased on some set of characteristics, not necessarily your own. Some examples are below: 1. “What is the best kind of apple to eat?” 2. “Who is the best impressionist painter?” 3. “How would you feel if you had blue hair?” These types of questions require you to make some kind of judgment. The tricky part is that you can’t just assume that the question is asking you to use your particular set of feelings about the world, or that you can apply your opinion to anything. We view different situations and idea with different sets of lenses. For example, you might be able to determine the relative value of a racehorse and a painting, but you certainly wouldn’t be looking for the same things in each case. So it’s important to be able to identify what particular set of characteristics you should use to evaluate something, then make sure you can back up your evaluation with concrete evidence. Even beauty can have evidence; a person’s eyes, hair or clothes might make them beautiful. The exciting part is that there are rarely “correct” answers to evaluation questions, so long as you can back up what you say in a logical way. These questions are almost always essay or short-answer questions, because they ask you to take in information, compare it to a set of characteristics, then explain what you did. Just because you need to write a bit doesn’t make it difficult; just make sure you keep the objectives of the question in mind when you’re working. 1. Really, truly, the easiest way to study for these types of questions is to write a lot. Example: You can keep a journal, make your own newspaper articles about current events, start a blog, post on someone else’s blog, respond on online forums. Any form of writing will make it easy for you to express your thoughts clearly! 2. Pretend you are a lawyer and you need to win a case in favor of your particular assignment. By thinking out your argument, you will come across a lot of different characteristics of whatever topic you’re working on. Example: Prepare to defend the chloroplast who has been accused of not making enough sugar. What factors might influence this? How could you defend the poor chloroplast? 3. Pretend you’re writing a report to the head of a company. By listing all the attributes of what your topic has done over a year, you will more completely understand it. Example: Provide a year-end report about a company that makes airplanes. Explain what materials were used, how much of each material, the cost, any potential savings and suggestions for future directions of the company. Name _________________________________________________ Date ______________________ Period _______________ So You Want to Study for a Test part eight: rigor and relevance Bloom worked on his Taxonomy way back in 1956. While it’s still a useful tool, we’ve come a long way as a society, country and species since then. We’ve put people in space, built supersonic planes and invented the internet. So it behooves us to take good ol’ Bloom and update him a bit. The matrix below shows you how Bloom’s ideas match up with some real-life expectations. For example, if you’re doing an activity that falls in area A on the matrix, you’re not using very high level thinking, and you’re not applying skills that can be used in real life. THIS IS NOT A BAD THING. For example, the first time you learn to ride a bike, you don’t want to be analyzing and evaluating the bike, or trying to figure out what to do if you hit a bump. You just want to focus on acquiring the skill of not falling over. Then, once you have mastered the basic skillz, you can move on to higher level thinking.