AT: Legalism K

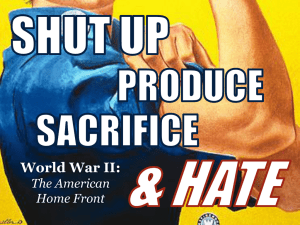

advertisement