Describing-accents

advertisement

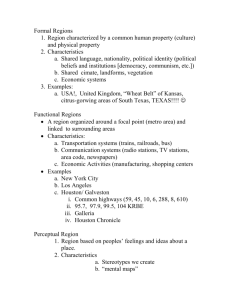

LELA 10082 Lecture II Describing accents II 1/22 Differences between X and RP 1. Differences of phoneme system Additional phoneme distinctions; “missing” phonemes 2. Differences of distribution X and RP have equivalent phonemes, but the phonetic contexts in which they occur differ 3. Differences of incidence X and RP have equivalent phonemes, but in particular words, a different phoneme is chosen 4. Differences of realisation X and RP have equivalent phonemes, but the phonetic and/or allophonic realisation differs 2/22 3. Differences of incidence • One phoneme rather than another in certain words – Systematic differences more interesting – Some differences are more arbitrary • Accents have both phonemes (or equivalent) • Difference can be defined in terms of phonetic (or other) context/condition 3/22 3. Differences of incidence • Northern “flat A” – Note “flat” is not a phonetic term: /a/~/A/ (front~back) • Northern accents have /a/ rather than /A/ before voiceless fricatives and consonant clusters beginning with a nasal: laugh, path, pass, sample, answer, aunt, branch, slander – But some exceptions: pant, romance, mansion, band, camp • But /A/ when there’s an ‘r’ or ‘l’ in the spelling, or before voiced fricatives: half, hearth, calm, farm, parcel, father, camouflage, and a few other words 4/22 3. Differences of incidence (1) pat, bad, cap, can, gas, land (2) path, laugh, grass (3) dance, grant, demand (4) part, bar, cart (5) half, palm, banana, can’t How do you pronounce these words? • RP /a/ in (1), /A/ elsewhere • Midlands, N England /a/ in (1)-(3) • Scots, N Irish has only /a/ in all 5 • SW England contrast is variable, but mostly have long [a] (ie /A/?) • All of the above subject to exceptions 5/22 Northern A • Some words with /a/ look like they should have /A/, giving rise to hypercorrection, and even some variation in RP – gas, salmon, graphic, lather, transfer, plastic, elastic, Elastoplast, gymnastic, Atlantic, Gesellschaft (!) • Realisation of /A/ varies in Northern accents (more later) /a/ in path /A/ in path Contrast absent or in doubt 6/22 3. Differences of incidence • Conservative RP has // rather than // before voiceless fricative in off, lost, cloth • Some Northern accents have /u/ rather than // where there is ‘oo’ in spelling, eg look, book, cook – Hypercorrection tooth /tT/ – System shift: luck~look~Luke /lk~luk~ljuk/ • Some Northern accents have // rather than (expected) // where there is ‘o’ in spelling, eg once, tongue, one, none, nothing, among 7/22 4. Differences of realisation • Especially in the vowel systems, many accents have same number of phonemes, used in the same words, but they differ phonetically – often systematically • Quite often we see the whole vowel system “shifted round” in some way • Example: – RP and Brummie 8/22 bee boy bay RP Brummie bee boy bay buy buy 9/22 4. Differences of realisation • Tyneside “inverted diphthongs” • Belfast similar • Diphthongs appear as monophthongs in several accents RP Tyneside example eI o u a – /eI/ = /e/ in Scots, /E/ in Lancs – /ou/ = /o/ in Scots, // in Lancs – etc. • /A/ is long /a/ in Scouse: cat~cart • Realisations sometimes make systematicity more obvious 10/22 4. Differences of realisation • Scouse voiceless stops /p,t,k/ affricated, or even realized as fricatives (esp. in word-final position, and especially /t/): – cup [kp, kp, kxp, x] ( = bilabial fricative) – but [bts, bts, bs] so but = bus – back [bakx, bax] – echo [Exu] • Stop phonemes in general characterized by lax articulation, leading to affrication or replacement by fricatives – bread and butter [brEz n bsE] 11/22 4. Differences of realisation • Equivalent phonemes (sometimes called “diaphone”) • Particularly vowel phonemes, absolute differences can be quite significant • Experimental evidence shows that hearers can adjust to the appropriate vowel system within a few utterances … • … even if the accent is unfamiliar • This underlines the idea of systematicity 12/22 4. Differences of realisation u /ou/ as in go u, E, ou Eo u a u u 13/22 Beyond phonemes • Suprasegmentals – Intonation • Patterns • Range – Stress, Rhythm, Loudness • Voice quality features 14/22 Intonation • Accents can differ in use of intonation patterns • Patterns described in terms of start position (high, mid, low) and direction (rise, fall, fall-rise, steady) • Pattern differences, like phonemes, can be analysed as follows – (see Ladd DR 1996. Intonational Phonology. Cambridge:CUP) – – – – Semantic differences (same tune, different meaning) Systemic differences (same meaning carried by different tune) Realisation differences Phonotactic differences (intonation patterns combine in different ways) • Lots of work done on IViE corpus – Multiple recordings of nine urban accents from around the British Isles – http://www.phon.ox.ac.uk/IViE/ 15/22 Intonation • Semantic differences: same tune different meaning • Systemic differences: same meaning different tune • Some overlap here: our example could be either semantic or systemic 16/22 Intonation: example • Use of (mid) rise in declarative statements • Most accents of English use low rise for yes/no questions or requests for confirmation – Did you go the party? – Who was at the party? • Same intonation when used with declarative statement implies element of questioning, eg request for confirmation – I come from Wigan (have you ever heard of it?) • This pattern increasingly used for simple declaratives – Evidence that this use originated with Australian adolescent females, spread to males, and then spread overseas, through soaps, though it is also a feature of some British accents, notably Ulster 17/22 Intonation: example • From Grabe E, Post B “Intonational variation in the British Isles”, in [book], available at http://www.phon.ox.ac.uk/~esther/GP2002.d oc • Intonation used for declarative statements • Data based on multiple recordings of informants from various regions 18/22 Intonation range • Even if patterns are the same, a difference in range may be typical of an accent • “Range” means how high/low the rises and falls are • Some accents characterised as “sing song” – eg South Wales, Brummie • Range variation can also be idiolectal 19/22 Stress, rhythm, loudness • Stress placement in individual words, or (rarely) in general, can be dialectal (eg Newcastle), and also interacts with choice of phoneme (weak forms) • Rhythm differences are usually idiolectal, but can be associated with regional dialects – eg some rural accents characterised as having a slower pace of delivery – Some non-UK accents might have distinctive rhythmic patters due to influence of other local languages (eg West Indian accents have more even rhythm, fewer weak forms) – Once again, beware of sociological stereotyping that has nothing to do with linguistics! • Loudness differences are almost always idiolectal – Some languages are typically louder than others, but this doesn’t seem to be the case with accents 20/22 Voice quality features • Voice quality include things like pitch, range and loudness, but also eg – Breathiness, nasality, pharyngealisation, velarisation, … • Voice quality usually idiolectal, but there are some regional tendencies 21/22 Voice quality features • Several accents can be described as “nasal” – New York, middle class southern English • Liverpool and N Wales accents often have a velarised or pharyngealised quality: tongue is raised towards back of mouth, giving a “strangled” quality • Some southern Irish accents can sound “breathy” due to (pre-)aspiration of stops (influence of Gaelic), and weak voicing of vowels • Flexibility of lip-movement might give an accent a certain quality (tight- or stiff- lipped) 22/22