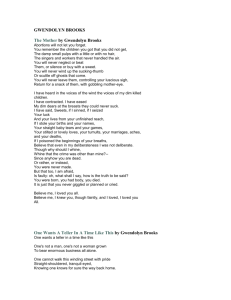

Gwendolyn Brooks Packet

advertisement

Gwendolyn Brooks From Annie Allen 1. the birth in a narrow room Weeps out of western country something new. Blurred and stupendous. Wanted and unplanned. Winks. Twines, and weakly winks Upon the milk-glass fruit bowl, iron pot The bashful china child tipping forever Yellow apron and spilling pretty cherries. Now, weeks and years will go before she thinks "How pinchy is my room! how can I breathe! I am not anything and I have got Not anything, or anything to do!"But prances nevertheless with gods and fairies Blithely about the pump and then beneath The elms and grapevines, then in darling endeavor By privy foyer, where the screenings stand And where the bugs buzz by in private cars Across old peach cans and jelly jars. 1 Gwendolyn Brooks 2. Maxie Allen Maxie Allen always taught her Stipendiary little daughter To thank her Lord and lucky star For eye that let her see so far, For throat enabling her to eat Her Quaker Oats and Ceram-of-Wheat, For tongue to tantrum for the penny, For ear to hear the haven’t-any, For arm to toss, for leg to chance, For heart to hanker for romance. Sweet Annie tried to teach her mother There was somewhat of something other. And whether it was veils and God And whistling ghosts to go unshod Across the broad and bitter sod, Or fleet love stopping at her foot And giving her its never-root To put into her pocket-book, Or just a deep and human look, She did not know; but tried to tell. Her mother thought at her full well, In inner voice not like a bell (Which though not social has a ring Akin to wrought bedevilling) But like an oceanic thing: What do you guess I am? You’ve lots of jacks and strawberry jam. And you don’t have to go to bed, I remark, With two dill pickles in the dark, Nor prop what hardly calls you honey And gives you only a little money. 2 Gwendolyn Brooks From Maud Martha 1. Description of Maud Martha What she liked was candy buttons, and books, and painted music (deep blue, or delicate silver) and the west sky, so altering, viewed from the steps of the back porch: and dandelions. She would have liked a lotus, or China asters or the Japanese Iris, or meadow lilies—yes, she would have liked meadow lilies, because the very word meadow made her breath more deeply, and either fling her arms or want to fling her arms, depending on who was by, rapturously up to whatever was watching in the sky. But dandelions were what she chiefly saw. Yellow jewels for everyday studding the patched green dress of her back yard. She liked their demure prettiness second to their everydayness; for in that latter quality she thought she saw a picture of herself, and it was comforting to find that what was common could also be a flower. And could be cherished! To be cherished was the dearest wish of the heart of Maud Martha Brown, and sometimes when she was not looking at dandelions (for one would not be looking at them all the time, often there were chairs and tables to dust or tomatoes to slice or beds to make or grocery stores to be gone to, and in the colder months there were no dandelions at all), it was hard to believe that a thing of only ordinary allurements—if the allurements of any flower could be said to be ordinary00was as easy to love as a thing of heart-catching beauty. Such as her sister Helen! Who was only two years past her own age of seven, and was almost her own height and weight and thickness. But oh, the long lashes, the grace, the little ways with the hands and feet. 3