Unit 7B Notes

advertisement

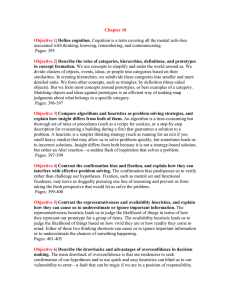

Unit 7B Notes: Cognition--Thinking, Problem Solving, Creativity, and Language Unit Overview The first part of Unit 7B deals with thinking, with emphasis on how people logically - or times illogically - use tools such as algorithms and heuristics when making decisions and solving problems. Also discussed is the type of thinking that leads to creativity, as well as several common obstacles to problem solving. These include fixations that prevent us from taking a fresh perspective on a problem and our bias to search for information that confirms rather than challenges existing hypotheses. The section concludes with discussions of the power and perils of intuition and the effects of framing on decision making. The rest of the unit is concerned with language, including its structures, development in children, and relationship to thinking. Two theories of language acquisition are evaluated: Skinner's theory that language acquisition is based entirely on learning and Chomsky's theory that humans have a biological predisposition to acquire language. Interconnecting----This content links well with concepts in other units: Thinking: connect this content with Unit 2, Research Methods, where Myers discusses scientific thinking. Problem solving: connect this content with Unit 14, Social Psychology, where Myers discusses stereotyping. Creativity: connect this content with Unit 11, Testing and Individual Differences, where Myers discusses definitions of intelligence. Language: connect this content with Unit 9, Developmental Psychology, where Myers discusses cognitive development. Thinking 1. Define cognition, and describe the roles of categories, hierarchies, definitions, and prototypes in concept formation. Cognition refers to the mental activities associated with thinking, knowing, remembering, and communicating. Cognitive psychologists study these activities including the logical and illogical ways we create concepts, solve problems, make decisions and form judgments. To think about the countless events, objects, and people in our world, we organize them into mental groupings called concepts. To simplify things further, we organize concepts into category hierarchies. Although we form some concepts by definition - for example, a triangle has three sides - more often we form a concept by developing a prototype, a mental image or best example of a particular category. For example, a robin more closely resembles our "bird" category than does a penguin. The more closely objects match our prototype of a concept, the more readily we recognize them as examples of a concept. Once we place an item in a category, our memory of it later moves in the direction of the category prototype. Jean Piaget’s idea of schemas (Unit 9): Piaget called the basic unit of cognition a schema, and upon these schemas people would base their conceptions of the world. As people process information, they will either assimilate it or accommodate it. Assimilation involves putting the new information into an existing category. Accommodation requires one to change or adapt a category to suit the new information that conflicted with or added to the old category. 2. Compare algorithms, heuristics, and insight as problem-solving strategies, and identify the factors associated with creativity. We approach some problems through trial and error, attempting various solutions until stumbling upon one that works. For other problems, we may follow a methodical rule or step-by-step procedure called an algorithm. Because algorithms can be laborious, we often rely instead on simple thinking strategies called heuristics. Speedier than algorithms, heuristics are also more error-prone. Sometimes, however, we are unaware of using any problemsolving strategy; the answer just comes to us as a sudden flash of insight. Researchers have identified brain activity associated with insight. Teaching tip: you can study more effectively if you are adept at making concept hierarchies (mind maps). Textbooks are commonly divided into these hierarchies. Main concepts are usually put in bold and in typeface that is bigger than normal text. Sub-concepts fall under each main category, and while these have a different look as well, they aren’t as big or bold as the main concepts. Finally, important terms fall within the narrative of the textbook, but are usually in boldface to separate them from other words. When you use SQ3R, you will recognize these concept hierarchies as you study, then you will see the big picture the textbook authors are trying to communicate, leading to better understanding the text. Connect Myer’s discussion of problem solving with Unit 7A by understanding how you view problems can determine whether or not you will succeed in solving them. If you are generally pessimistic, then you will view problems as obstacles that pervade and ruin your life. If you are optimistic, you will tend to view problems as challenges YOU have the power to overcome! In general, a certain level of aptitude is necessary but not sufficient for creativity (the ability to produce novel and valuable ideas). Studies suggest five other components of creativity: expertise, imaginative thinking skills, a venturesome personality, intrinsic motivation, and a creative environment. The brain regions supporting the convergent thinking tested by intelligence tests (requiring a single correct answer) differ from those supporting the divergent thinking that imagines multiple solutions to a problem (such as how many uses you can think of for a brick). Troubleshooting: People often get convergent and divergent thinking confused. To see the difference focus on the root words: converge (meaning, to come together to one point) and diverge (meaning, to separate into multiple points). Convergent thinking requires focusing on one answer, while divergent thinking asks people to consider multiple answers. Intrinsic motivation is discussed more thoroughly in Unit 8A. Intrinsic motivation is different from extrinsic motivation, which is based on external rewards rather than internal ones. People who are creative don’t necessarily need external rewards in order to pursue their interests. 3. Explain how confirmation bias and fixation can interfere with effective problem solving. A major obstacle to problem solving is our eagerness to search for information that confirms our ideas, a phenomenon known as confirmation bias. This can mean that once people form a wrong idea, they will not budge from their illogic. Another obstacle to problem solving is fixation - the inability to see a problem from a fresh perspective. The tendency to repeat solutions that have worked in the past is a type of fixation called mental set. It may interfere with our taking a fresh approach when faced with problems that demand an entirely new solution. Our tendency to perceive the functions of objects as fixed and unchanging is called functional fixedness. Perceiving and relating familiar things in new ways is an important aspect of creativity. 4. Explain how the representativeness and availability heuristics can cause us to underestimate or ignore important information, and describe the drawbacks and advantages of overconfidence in decision making. The representativeness heuristic involves judging the likelihood of thinking in terms of how well they seem to represent, or match, particular prototypes. If something matches our mental representation of a category, the fact usually overrides other considerations of statistics or logic. The availability heuristic operates when we base our judgments on the availability of information in our memories. If instances of an event come to mind readily, perhaps because of their vividness, we presume such events are common. Both heuristics enable us to make snap judgments. However, these quick decisions sometimes lead us to ignore important information or to underestimate the changes of something happening. The representativeness heuristic is a form of stereotyping. We judge people according to the likelihood that they fit our representation of groups to which we feel they should belong! I like the “bumper” sticker quote on pg. 305! Overconfidence, the tendency to overestimate the accuracy of our knowledge and judgments, can have adaptive value. People who err on the side of overconfidence live more happily, find it easier to make tough decisions, and seem more credible than those who lack self-confidence. At the same time, failing to appreciate one's potential for error when making military, economic, or political judgments can have devastating consequences. Myers points out that overconfidence has its benefits. It is important to point out that many of the concepts in this unit – heuristics, framing, overconfidence, belief perseverance – do have their drawbacks, but if they did not have any value, people would not rely on them so much. If we use these concepts in this unit appropriately, they can add value to our lives by making decision making easier. 5. Describe the effects that belief perseverance, intuition, and framing can have on our judgments and decisions making. We exhibit belief perseverance, clinging to our ideas in the face of contrary evidence, because the explanation we accepted as valid lingers in our minds. Once beliefs are formed and justified, it takes more compelling evidence to change them than it did to create them. The best remedy for this form of bias is to make a deliberate effort to consider evidence support in the opposite position. Belief perseverance may be an underlying reason for the results found in the “Pygmalion in the Classroom” study by Robert Rosenthal and colleagues in 1972. This famous study demonstrated that teachers’ expectations can influence whether students perform well in school. Teachers who believe their students are not capable may not change their minds if they see evidence to the contrary. Although human intuition is sometimes perilous, it can be, whether conscious or unconscious, remarkably efficient and adaptive. Moreover, it feeds our expertise, our creativity, our love, and our spirituality. Smart intuition is born of experience. As we gain expertise in a field, we become better at making quick, adept judgments. Experienced nurses, firefighters, art critics, hockey players, and anyone who develops a deep and special knowledge learn to size up a situation in an eye-blink. Intuition is powerful, but sometimes perilous, and especially so when we over-feel and under-think, as we do when judging risks. So, we need to check our intuitions against reality. Check out Confucius’ quote on pg. 307 (what is knowledge.) The same issue presented in two different but logically equivalent ways can elicit quite different answers. This framing effect suggests that our judgments and decisions may not be well reasoned and that those who understand the power of framing can use it to influence important decisions - for example, by working survey questions to support or reject a particular viewpoint. Teaching tip: People can be seduced by the way products are framed. For example, people may buy more during a “25% off” sale even though they may end up spending more money than they would if there hadn’t been a sale. Also, people tend to over-eat foods that are labeled “low-fat,” believing that more of that food is the same as smaller serving of higher-fat foods, instead of realizing that the amount of fat they consume in either case is about the same. Myers suggests that sleeping on a problem may produce the best results for decision making. Refer to Unit 5 for a discussion of the work of William Dement, who showed that people can solve brain teaser better after having slept on the problem. Remember….. a good night’s sleep is one of the most important factors in good performance! The two-track mind is a recurring idea in psychology. Parallel processing, discussed in Unit 7A, is one way our two-track mind works. We can work consciously on one task while thinking unconsciously about other tasks. This often results in creative thinking and insight, as discussed elsewhere in this unit. Check out Table 7B.1 on pg. 310 Language 6. Describe the basic structural units of a language, including the rules that enable us to communicate meaning. Language is our way of combining words to communicate meaning. Spoken language is built from basic speech sounds, called phonemes; elementary units of meaning, called morphemes, and words. Finally, language must have a grammar, a system of rules that enables us to communicate with and understand others. Semantics refers to the rules we use to derive meaning from the morphemes, words, and sentences; syntax refers to the rules we use to order words into grammatically sensible sentences. In all 6000 human languages, the grammar is intricately complex. Teaching tip: some scholars have called language the most complex body of knowledge known to humanity. Consider this: Languages are composed of a limited number of symbols that can be combined according to particular rules. These symbols and rules can then be put together to create an unlimited number of messages. As long as someone is using the basic symbols and follows the basic rules of the languages, he or she can be understood! What an amazing ability we have! 7. For example: Even language that doesn’t make meaningful sense can still be grammatically correct – and be understood. o What is so unusual about the sentence below? (Aside from the fact it does not make a lot of sense.) “Jackdaws love my big sphinx of quartz.” o Answer: It’s the shortest sentence in the English language that includes every letter of the alphabet! Grammar is more than just a set of rules students learn in English class. o Mechanics are rules that govern how language is written. These are the concepts around which most English grammar lessons are structured. Use of commas, capitalization, and end mark rules are considered part of English mechanics. o Pragmatics are the usually unwritten rules about what language is appropriate to use at particular times. People use language differently in a job interview than when they are hanging out with friends. Trace the course of language acquisition from the babbling stage through the two-word stage. Children's language development moves from simplicity to complexity. Their receptive language abilities mature before their productive language. Beginning at about 4 months, infants enter a babbling stage in which they spontaneously utter various sounds at first unrelated to the household language. By about age 10 months, a trained ear can identify the language of the household by listening to an infant's babbling. Around the first birthday, most children enter the oneword stage, and by their second birthday, they are uttering two-word sentences. This two-word stage is characterized by telegraphic speech. This soon leads to their uttering longer phrases (there seems to be no "Three-word stage), and by early elementary school, they understand complex sentences. Teaching tip: Babies even younger than 4 months old use language. Cooing occurs at around 3-5 weeks of age. Infants at this age will repeat basic vowel sounds without using consonants. Holographic speech appears around one year of age and involves using single words to stand for a whole sentence of meaning. For example, the word “ball” could mean “I want the ball” or “Where is the ball?” depending on the inflection. Teaching tip: When you read Table 7B.2, on pg. 316, remember that the timeline given is NOT set in stone. The developmental milestones provided here are averages. In development, the sequence of language development is set, but the timeline is not. Babies vary in when they reach these milestones. 8. Discuss Skinner's and Chomsky's contributions to the nature-nurture debate over how children acquire language;, and explain why statistical learning and critical periods are important concepts in children's language learning. The debate between the behaviorist view that emphasizes learning and the view that each organism comes with innate predispositions surfaces again in theories of language development. Representing the nurture side of the argument, behaviorist B.F. Skinner argued that we learn language by the familiar principles of association (of sights of things with sounds of words), imitation (of words and syntax modeled by others), and reinforcement (with success, smiles, and hugs after saying something right). Challenging this claim, and representing the nature side of the debate, Noam Chomsky notes that children are biologically prepared to learn words and use grammar (they are born with what Chomsky called a language acquisition device already in place). He argues that children acquire untaught words and grammar at too fast a rate to be explained solely by learning principles. Moreover, there is a universal grammar that underlies all human language. Cognitive neuroscientists suggest that the statistical analysis that children perform during life's first years is critical for the mastery of grammar. Skinner's emphasis on learning helps explain how infants acquire their language as they interact with others. Chomsky's emphasis on our built-in readiness to learn grammar helps explain why preschoolers acquire language so readily and use grammar so well. Nature and nurture work together. Childhood does seem to represent a critical (or "sensitive") period for certain aspects of learning. Research indicates that children who have not been exposed to either a spoken or signed language by about age 7 gradually lose their ability to master any language. Learning a second language also becomes more difficult after the window of opportunity closes. For example, adults who attempt to master a second language typically speak it with the accent of their first. Teaching tip: most researchers recognize a distinctions between “critical” and sensitive” periods. Typically, critical periods are more rigid than sensitive periods. Critical periods suggest a finite amount of time during which a skill must be learned. Sensitive periods suggest an ideal amount of time during which a skill ought to be learned, but if the skill is not learned in time, it can be learned eventually, but perhaps not as easily. Teaching tip: Noam Chomsky has been one of the most cited persons in academia over the last century. His study of language as a brain function rather than a social phenomenon led to the emergence of cognitive science as a dominant perspective in psychology. Not only has Chomsky been influential in the area of linguistics, but he has also been an ardent political activist. He has written several books protesting U.S. military endeavors carried out, as he believes, primarily to support U.S. interests abroad. 9. Discuss Whorf's linguistic determinism hypothesis in relation to current views regarding thinking and Language, and describe the value of thinking in images. Although Benjamin Whorf's linguistic determinism hypothesis suggests that language determines thought, it is more accurate to say that language influences thought. Language expresses our thoughts, and different languages can embody different ways of thinking. Many bilinguals report that they have a different sense of self, depending on which language they use. We use language in forming categories, and words can influence our thinking about colors. Perceived differences grow when we assign different names to colors. Given the subtle influence of words on thinking, we ought to choose our words carefully. Studies of the effects of the generic pronoun he and the ability of vocabulary enrichment to enhance thinking reveal the influence of words. We might say that our thinking influences our language, which then affects our thoughts. We often think in images. In remembering how we do things, for example, turning on the water in the bathroom, we use non-declarative (procedural) memory - a mental picture of how we do it. Artists, composers, poets, mathematicians, athletes, and scientists all find images to be helpful. Researchers have found that thinking in images is especially useful for mentally practicing upcoming events and can actually increase our skills. Research suggests that mental rehearsal can help one to achieve an academic goal. Teaching tip: Cognitive maps are mental representations of the spatial environment. They represent the world as we believe it to exist. If students are asked to think of the layout of the house in which they grew up, or are asked the shortest route from class to the library, they think in terms of images, not words. Sometimes our cognitive maps are very detailed and accurate; in other cases, they may be sketchy and bear little correspondence to reality. Overgeneralization: The concept of overgeneralization can be linked to Piaget’s concepts of assimilation and accommodation (Unit 9). As children learn the rules of language, they assimilate them into their language schemas. But some rules don’t apply to all words. Adults and older children correct them, and they gradually accommodate their schemas to include these exceptions, eventually learning how to speak in a more grammatically correct fashion as they age. Overgeneralization occurs in a couple of different ways. Sometimes children over-extend rules in the ways Myers points out in the text. In addition, they may call all four-legged animals “doggies” or all flying machines “airplanes.” At other times, children under-extend language rules. They will identify a certain object with a word and insist that only that object fits that description. For example, they may believe a “cookie” is a particular type of cookie, like chocolate chip. This type of mistake can be frustrating if you don’t have anything other than chocolate chip cookies available!