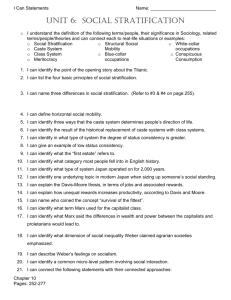

Chapter 7 Social Stratification: United States and Global Perspectives

advertisement

Chapter 7 Social Stratification: United States and Global Perspectives Melanie Hatfield Soc 100 Wealth Your wealth is what you own. A house (minus the mortgage), a car (minus the car loan), and some appliances, furniture, and savings (minus the credit card debt). Bill Gates Wealth In the mid-1990s: The richest 1% of American households owned nearly 39% of all national wealth. The richest 10% owned almost 72%. The poorest 40% of American households owned .2% of all national wealth. The bottom 20% had negative net worth. Patterns of Wealth Inequality Wealth inequality has been increasing since the early 1980s. 62% of the increase in national wealth in the 1990s went to the richest 20%. The US has surpassed all other highly industrialized countries in wealth inequality. Between 50 and 80% of the net worth of American families now comes from transfers and inheritances. Policies that seek to redistribute income from the wealthy to the poor may not get at the root of economic inequality. The Distribution of National Income among Households, US Global Inequality Almost 20% of the world’s population lacks adequate shelter. Over 20% lacks safe water. About 1/3 of the world’s population are without electricity. Over 40% lack adequate sanitation. In the US, there are 626 phone lines for every 1,000 people, but in Cambodia, Congo, and Afghanistan there is only 1 line per 1,000 people. Global Inequality Annual health expenditures in the US is $2,765 per person, whereas in Vietnam it’s $3 per person. The average education expenditure for an American child is $11,329 per year, compared with $57 in China. The richest 10% of Americans earn 10,000 times more than the poorest 10% of Ethiopians. There are still about 27 million slaves in Mozambique, Sudan and other African countries. Inequality Global Inequality: Differences in the economic ranking of countries. Crossnational variations in internal stratification: Differences between countries in their stratification systems. Measuring Internal Stratification The Gini index is the measure of income inequality. Its value ranges from zero (which means that every household earn exactly the same amount of money) to one (which means that all income is earned by a single household). Household Income Inequality Inequality and Development Foraging Societies Societies in which people live by searching for wild plants and hunting wild animals. Predominated until about 10,000 years ago. Inequality, the division of labor, productivity, and settlement size are very low in such societies. Horticultural and Pastoral Societies About 12,000 years ago, people established agricultural settlements based on horticulture and pastoralism. These innovations enabled people to produce a surplus above what they needed for subsistence. A small number of villagers controlled the surplus and significant social stratification emerged. Agrarian Societies People developed plow agriculture about 5,000 years ago and were able to increase production and surpluses. Agrarian societies developed religious beliefs justifying steeper inequality. People viewed large landowners as “lords.” If you were born a peasant, you and your children were likely to remain peasants. Industrial Societies Emerged in Great Britain in the 1780s. Productivity, the division of labor, and settlement size increased substantially. Social inequality was substantial during early industrialism and declined as the industrial system matured. Postindustrial Societies Societies in which most workers are employed in the service sector and computers spur increases in the division of labor and productivity. Shortly after World War II, the U.S. became the first postindustrial society and led the world into an era of prosperity social equality under the liberal “Development Project” up to early 1970s In most of the world, social inequality has been increasing - and accelerating - since early 1970s., under the neoliberal “Globalization Project Marx’s Theory of Stratification During the Industrial Revolution industrial owners were eager to produce more efficiently to earn higher profits, their competition drove them to ceaseless innovations, higher concentration, and increasing the absolute & relative exploitation of their labor. Thus, as the ownership class (bourgeoisie) grew richer and smaller, the working class (proletariat) grew larger and more impoverished: modernity led to exponential social inequality. Marx believed that capitalist growth would inevitably convulse in national proletarian revolutions, but also would lay, through “socialized production” the groundwork for a multistate world “socialist” society, which would eventually lead to no more classes (or states) and therefore no more class/international conflict: “communism” - no more social inequalities! Marx (cont.) Marx felt that industrial workers would ultimately become aware of their exploitation: “class consciousness” This would encourage class organizastion and mobilization in all “advanced” capitalist countries: the growth of unions & workers’ political parties. These “vanguard” organizations would eventually win state power and implement the socialist program: “From each according to their ability, to each according to their work” usher a new “communist” world in which there would be no private wealth: “From each according to their ability, to each according to their needs.” Critical Evaluation of Marx’s Conflict Theory 1. 2. 3. Why didn’t things work out the way Marx predicted? They did, up to WWII! After WWII industrial societies did not polarize into 2 opposed classes engaged in bitter conflict. While Marx correctly argued that investment in technology makes it possible for capitalists to earn high profits, he did not expect investment in technology to also make it possible for rich country workers to earn higher wages in the era of imperialism: The New Deal! Socialism took root not where industry was most highly developed, as Marx predicted, but in semiindustrialized countries such as Russia in 1917 and in the colonial world (after China in 1948) Functionalist theories of inequality: The Davis-Moore Thesis This theory argues that inequality is necessary and desirable: Jobs in modern society differ in importance. How can the limited number of talented people be motivated to undergo the long training they need to serve? The incentives are money and prestige. Social stratification is necessary (or “functional”) because the prospect of high rewards motivates people to undergo the sacrifices needed to obtain higher education, etc., in a meritocratic society. Critical Evaluation of Functionalism 1. 2. 3. The question of which occupations are most important is not clear-cut. Also, what kind of “job” is being rich by inheritance? It stresses how inequality helps society discover talent, but it ignores the pool of talent lying undiscovered because of inequality. It fails to examine how advantages are passed from generation to generation. Weber’s Theory of Stratification Like the functionalists, Max Weber argued that the emergence of a classless society is highly unlikely. Like Marx, he recognized that under some circumstances people can act to lower the level of inequality in society. Weber recognized that 2 types of groups other than classes – status groups and parties – have a bearing on the way society is stratified. Weber’s Stratification Scheme Social Mobility Peter Blau and Otis Dudley Duncan did work on social mobility – The American Occupational Structure (1967). They took on the task of figuring out the relative importance of inheritance vs. individual merit in determining one’s place in the stratification system. Blau and Duncan’s answer was that America is based mainly on individual achievement heavily influenced by family & educational factors. Blau and Duncan’s Model of Occupational Achievement Social Mobility Other research has shown that from WWII-1960s: The rate of social mobility for men in the US was high and that most mobility was upward. Mobility within a single generation (intragenerational mobility) was generally modest. Mobility over more than one generation (intergenerational mobility) could be substantial. Most social mobility was the result of change in the occupational structure (known as structural mobility). There was only small differences in rates of social mobility among the highly industrialized countries. Group Barriers to Upward Social Mob. If you compare people with the same level of education and similar family backgrounds, women and members of racial/ethnic minority groups tend to attain lower status than white men. The existence of such group disadvantages suggests that American society is not as open as Blau and Duncan made it out to be. Prestige and Power Inequality is not based on money alone but also on prestige and power. Members of status groups tend to signal their rank by means of material and symbolic culture. They seek to distinguish themselves from others by taste in fashion, food, music, literature, manners, and travel, all of which is subject of mass marketing: cat & mouse Power Power is a second non-economic dimension of stratification: the ability to have commands obeyed. Power has a profound impact on the distribution of opportunities and rewards in society. Power is exercised formally in politics, and politics can reshape the class structure by changing laws governing people’s rights to own property, have access to opportunities & benefits, etc. U.S. Politics and the Plight of the Poor since 1980 Broadly speaking, most Democrats want government to play an important role in helping to solve the problem of poverty. Most Republicans want to reduce government involvement with the poor so people can solve their problems themselves through markets. We can see the effect on government policy on poverty by examining fluctuations in the poverty rate over time. The poverty rate is the percentage of Americans who fall below the “poverty threshold.” The Poverty Threshold To establish the “poverty threshold” the US Department of Agriculture first determines the cost of an economy food budget. The poverty threshold is set at three times that budget. It is adjusted for the number of people in the household, the annual inflation rate, whether the individual adult householders are younger than 65 years of age, whether they live in Hawaii or Alaska (where the cost of living is relatively high) or in the rest of the US. Poverty Rate The 1930s: The Great Depression During the Great Depression (1929-39), 30% of Americans were unemployed, and many of the people who had jobs were barely able to make ends meet. In response to the suffering of the American people and the large, violent labor strikes of the era, President Franklin Roosevelt introduced such programs as Social Security, Unemployment Insurance, and Aid to Families with Dependent Children (FDC). The Great Depression (Cont.) For the first time, the federal government took responsibility for providing basic provisions to citizens who were unable to do so themselves. Because of Roosevelt’s “New Deal” policies, and rapidly increasing prosperity in the decades after WWII, the poverty rate fell dramatically, reaching 19% in 1964. The 1960s: War on Poverty In 1964, President Lyndon Johnson declared a “war on Poverty.” Millions of southern blacks who migrated to northern and western cities in the 1940s and 1950s were unable to find jobs. Many African Americans demanded at least enough money from the government to allow them to survive. President Johnson soon broadened access to AFDC and other welfare programs. In 1973 the poverty rate dropped to 11.1%. The 1980s: “War against the Poor” Reagan explained the tough economic times the nation was having was the result of too much government. He argued that cutting government services and the taxes that fund those services supposedly stimulates economic growth and reduce relief to the poor. Many saw this as a “war against the poor.” Because a large proportion of welfare recipients were African Americans and Hispanics, some analysts believed that this move was fed by racist sentiment. Poverty rates rose. Myths about the Poor Myth 1: The majority of poor people are African- or Hispanic-American single mothers with children. In 2006, fully 44% of the poor were non-Hispanic whites Female-headed families represented 53% of the poor, 38% lived in married-couple families. Myths about the Poor Myth 2: People are poor because they don’t want to work. More than 37% of the poor over age 15 worked in 2006, nearly 12% full time. 44% of poor people are under age 18 or over 65. Many of the poor are unable to work due to health or disability issues. Myths about the Poor Myth 3: Poor people are trapped in poverty. Only about 12% of the poor remain poor 5 or more years in a row Myths about the Poor Myth 4: Welfare encourages married women with children to divorce so they can collect welfare, and it encourages single women on welfare to have more children. Women on welfare have a lower birthrate than women in the general population. Welfare payments are very low and recipients suffer severe economic hardship. Myths about the Poor Myth 5: Welfare is a strain on the federal budget. “Means-tested” welfare programs require recipients to meet an income test to qualify. Such programs accounted for only 6% percent of the federal budget in 2001. Perception of Class Inequality Research shows that we know we live a class-divided society. Why then do we think inequality continues to exist? Most Americans agree with the statement, “inequality continues because it benefits the rich and powerful.” Most Americans also agree with the statement, “inequality continues because ordinary people don’t join together to get rid of it.” Government’s Role in Reducing Poverty Despite widespread awareness of inequality and considerable dissatisfaction with it, most Americans are opposed to the government playing an active role in reducing inequality. Most Americans remain individualistic and self-reliant. On the whole, we persist in the belief that opportunities for mobility are abundant and that it is up to the individual to make something of those opportunities by means of talent and effort.