Jacaranda - Turquoise Moon

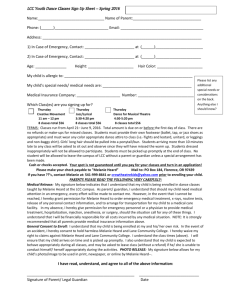

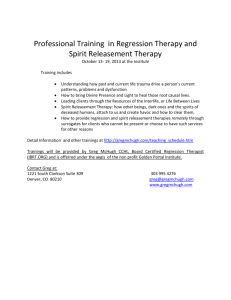

advertisement