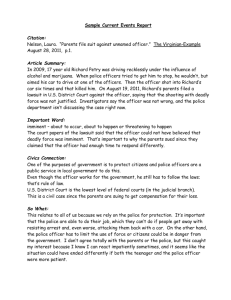

The Use of Restorative Justice by the Police in England and Wales

advertisement