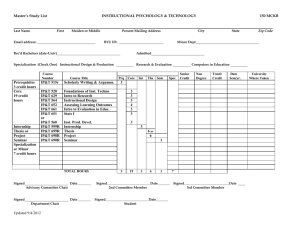

TI Proposal - East Carolina University

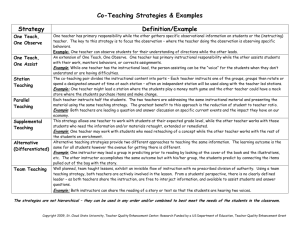

advertisement