Healy, Patrick - Queer Foundation

advertisement

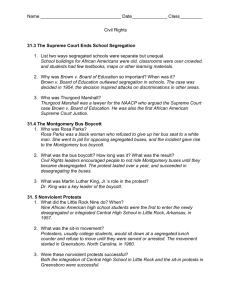

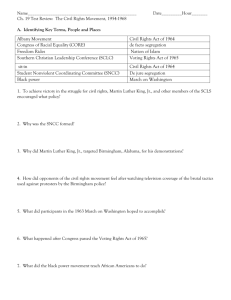

How did the events of the African American Civil Rights Movement in Alabama from 1950-1969 compare to the events of the Gay Rights Movement in California from 19601979? Patrick Healy Southeast High School Bradenton, FL Introduction African Americans and Homosexuals have historically been discriminated against in the United States. Both social groups have been victims of job persecution, police violence, and theft of human rights by legislature. Today, however, this prejudice is far less than it was in the 20th century.1 The shift in societal and legal attitudes towards African Americans and Homosexuals is attributed to the events of the African American Civil Rights Movement and the events of the Gay Rights Movement. In reference to the African American Civil Rights Movement, this investigation will focus on events occurring in Alabama between 1950 and 1969 that resulted in abolishment of segregation, advancement of African American voting rights, and creation of equality between African Americans and Whites. In reference to the Gay Rights Movement, this investigation will focus on events occurring between 1960 and 1979 that resulted in the abolishment of sodomy laws, creation of gay rights ordinances, and made it safe and comfortable for homosexuals to be open about their sexual orientation. The research question to be addressed is: How did the events of the African American Civil Rights Movement in Alabama compare to the events of the Gay Rights Movement in California? This topic is worthy of study because bigotry and the need for social change is an ever present issue in society. By comparing these two movements in relation to each other, their similarities and differences will make it apparent as to how prejudice is eradicated and that injustice is and has been present in many settings. Evidence for this argument will be derived from scholarly books, newspaper articles, documentaries, internet resources, interviews, and newscasts. It is evident that these social movements compare by the actions of the organizations supervising the movements, the types of protests used, the manner in which issues were dramatized, and the activities of leaders in the movements. 1 Pamela, 2014 Organizations and the Conditions of their Followers Despite the differences in the types of injustice experienced by African Americans and Homosexuals, both social groups dealt with extreme animosity from police forces. Police in Alabama often mistreated African Americans in multiple ways. Police would push African Americans on streets, call them racial slurs such as “nigger”, and enforce the laws of Jim Crowe with brute force. It was not uncommon for an African American to be beaten by Police if they came slightly too close to a facility designated Whites only or attempted to eat at an all-White dining location.2 In the early 1960’s police animosity towards homosexuals in California greatly increased.3 If two homosexuals were seen in public, police would commonly break them apart and possibly arrest them for public indecency.4 Essentially, any public display of homosexuality was met with violence as well as slurs such as “faggot” or “queer”. Known meeting places for homosexuals, such as parks, were also patrolled by Police, resulting in many arrests. 5 Police animosity towards homosexuals however was most commonly seen in bars catering to the homosexual community, known as gay bars. Police invaded gay bars and extorted customers by beating them with night sticks.6 In fact, this practice was so common that the heterosexual population of California expected it to occur.7 Both African Americans and Homosexuals experienced prejudice and police brutality, thus making a need for social reformation. In both social movements, overarching organizations were founded to mediate the events of the movements. Founded in Montgomery, AL in August 1957, the Southern Christian 2 Leeth, 2014 Bullough ,1997 4 Pamela, 2014 5 Bullough, 1997 6 Bullough, 1997 7 Epstein, 1984 3 Leadership Conference (SCLC) played a large role in organizing protests and demonstrations for the African American Civil Rights Movement. The SCLC was created from the Montgomery Bus Boycott and elected Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. as its first president.8 The SCLC worked throughout the Southern United States but its influence was present most in Alabama.9 The Gay Rights movement counterparts to the SCLC are the Mattachine Society and Taverns Guild. The Mattachine Society is considered the earliest gay rights organization.10 Founded in 1950 by Harry Hay and several other homosexuals in Los Angeles, CA, the Mattachine Society focused primarily on self-discovery for homosexuals as well as improvement and protection of their rights.11 By 1953 the Mattachine Society had over 100 chapters in Southern California. The Taverns Guild was a union among gay bars to protect each other, prevent police raids, and advance homosexual rights.12 The Taverns Guild was first established among bars in San Francisco in the mid 1950’s but soon extended to Los Angeles.13 The SCLC, Mattachine Society, and Taverns Guild played similar roles in their respective social movements because of their overarching nature. Action was organized throughout Alabama and California by these organizations. In addition, all 3 of these organizations also held voting registration drives.14 15 This voter registration allowed African Americans and Homosexuals to be involved in elections, thus providing the influence to pass or eradicate legislation and representatives to promote their rights. More specifically, both movements also had smaller organizations which worked at a local level. For example, the Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA) was the group 8 Steele, 2010 Carrier, 2004 10 Bullough, 1997 11 Adam, 1995 12 Bullough, 1997 13 Adam, 1995 14 Sargent, 2004 15 Bullough, 1997 9 responsible for organizing and controlling the Montgomery Bus Boycott.16 The San Franciscan Society of Individual Rights (SIR) was also an organization in the Gay Rights Movement which focused on San Francisco.17 All of these organizations, both overarching and local, had to fundraise. The SCLC thrived on donations by benefactors. Martin Luther King acquired donations for the SCLC from lawyers of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), an organization that worked throughout the United States for African American rights.18 SIR held events to raise money for the cause. One specific instance of this was a New Year’s Eve Ball held at the Glide Memorial Baptist Church.19 It was one of the largest events held to promote homosexual rights, therefore it was a target for police to intervene. During the festivities, police invaded the ball claiming a safety inspection, thus causing commotion resulting in multiple arrests and some violence.20 The event was monitored by the media which made it a prime public example of police animosity towards homosexuals.21 The conditions before the African American Civil Rights Movement and Gay Rights Movement both contain injustice and police brutality. Proprieting these movements took the efforts of both national and local organizations having protests and voter registration drives. The Montgomery Bus and Coors Beer Boycotts Boycotts are a form of economic protest in which a group of people refuse to use a service or business in revolt against some issue. In the African American Civil Rights Movement, no boycott is as infamous as the Montgomery Bus Boycott. In Montgomery, AL African Americans were required to sit in the back of public buses, and, if more White 16 Winters, 2000 Alensas, 2008 18 Carrier, 2004 19 “Cops invade homosexual,” 1965 20 Alensas, 2008 21 “Cops invade homosexual,” 1965 17 passengers got on, give up their seats.22 This was the common practice until the evening of December 1, 1955 when Rosa Parks, an African American seamstress, refused to give up her seat to a White man.23 Despite being ordered by the bus driver to move, Parks held her ground. She was promptly arrested and found guilty of violating segregation laws.24 This arrest caught the attention of the NAACP which decided to use Parks’ arrest as the platform to begin a boycott of the buses in Montgomery.25 Flyers were printed and distributed announcing a boycott of the buses to begin on December 5th, the following Monday. At a meeting of African American leaders in Montgomery, Martin Luther King Jr. was elected to lead the boycott, and the MIA was founded to help run the mass protest.26 African Americans were to boycott the bus system until the following demands were met: No more segregation on the buses, and the hiring of African American bus drivers on primarily African American routes.27 African Americans were common patrons of the public bus system, thus their absence created economic distress for the city of Montgomery. In order to sustain the boycott, an intense network of carpooling was formed and many people walked.28 During the time of this boycott, animosity of Montgomery police towards African Americans was increased. The animosity was so intense that Montgomery even adopted a “get tough” policy in which police tried to force African Americans on the buses using force and intimidation.29 In addition, the homes of both Martin Luther King Jr. and E.D. Nixon were bombed by White supremacists;30 tension in Montgomery was high. Despite the violence and hardship, on November 13, 1956, the United States Supreme Court ruled that segregation on 22 Sargent, 2004 Barron, 2013 24 Barron, 2013 25 Sargent, 2004 26 Sargent, 2004 27 Winters, 2000 28 Sargent, 2004 29 Sargent, 2004 30 McKissack, 1991 23 public buses was unconstitutional and on December 20, 1956 the demands of the MIA were met and the boycott ended.31 The African Americans rode again, but unsegregated. The Montgomery Bus Boycott was one of the first major victories of the African American Civil Rights movements. It demonstrated the influence of African Americans when they stood together and established boycotts as a useful means of protest. In the Gay Rights Movement, there is also a significant boycott, the Coors Beer Boycott of San Francisco, CA. However, the Coors Boycott held significance in a different way than the Montgomery Bus Boycott. The brainchild behind this boycott was Harvey Milk. Milk was a resident of San Francisco, CA, living in a neighborhood called The Castro, a predominantly homosexual neighborhood. Before Milk arrived, the straight-owned businesses of the Castro discriminated against homosexuals and treated them unjustly. Milk changed this by making lists of those businesses which were gay-friendly and those which were not. The homosexuals of The Castro then did not shop at the non-gay-friendly stores, and they went out of business.32 However, this small boycott was the predecessor of the Coors Beer Boycott. Coors Beer at this time had a well-known history of being conservative and anti-labor union. Many cities around the country were attempting to boycott Coors Beer, but unsuccessfully.33 The homosexual population’s influence in eradicating homophobic businesses caught to the attention of Alan Behr, the president of the San Francisco chapter of the Teamsters Union.34 Behr met with Harvey Milk and asked him to help them with the Coors Beer Boycott. Within a month, Milk and the homosexual population of San Francisco got Coors Beer out of every gay bar in the city. The momentum only progressed from there, eventually all bars got rid of the beer, and San Francisco 31 Sargent, 2004 Van Sant, 2008 33 Van Sant, 2008 34 Epstein, 1984 32 was successfully boycotting Coors.35 The Coors Beer Boycott did not directly advance Gay Rights. However, its success with the help of homosexuals established the homosexual population as influential. Also, Harvey Milk gained strong allies with the Teamsters and other labor unions. Harvey Milk was later elected to the San Francisco Board of Supervisors, and became the first openly gay man elected to public office in the United States.36 Milk’s allies gained in the Coors Beer Boycott contributed significantly to this success. The Montgomery Bus Boycott and Coors Beer Boycott are both significant economic protests in their respective social movements. They were both great victories and established African Americans and Homosexuals as influential social groups, providing momentum for their movements. Dramatization of Issues Social movements are made up not only of protests, but also demonstrations. A demonstration in a social movement is an activity performed by the members of the movement that may seem unrelated to the issue but nevertheless dramatizes the issues and creates change. In the African American Civil Rights Movement some of the most powerful demonstrations are the marches of African Americans and their supporters from Selma, AL to Montgomery, AL in protest of ludicrous voting laws in Selma. In order to create change, the legislature must be voted on, and the African Americans needed to vote to create this change. However, in Selma, there existed ridiculous voting laws that prevented African Americans from being able to register to vote. One of these was the Grandfather Clause in which a person could not register if their grandfather was a slave; this eliminated most of the African American population. Another such practice was an impossible literacy test which the African Americans could not pass, and thus 35 36 Epstein, 1984 Russell, 1995 could not register to vote.37 In response to this injustice, the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and SCLC organized a march from Selma to Montgomery to take place on March 7, 1965. 600 people began at the Brown Chapel in Selma and marched toward Montgomery.38 As the marchers made their way out of Selma they encountered a hoard of AL state troopers on the Edmund Pettus Bridge. The troopers ordered the demonstrators to turn back but they continued on. The troopers then retaliated on the marchers by beating them with clubs and releasing tear gas. The marchers dispersed and these acts of violence gave March 7, 1965 the name “Bloody Sunday”. On March 9, 1965, another march was held but instead of crossing the Edmund Pettus Bridge and risk more violence, the marchers knelt in prayer and then turned around, giving this day the name, “Turnaround Tuesday”.39 President Lyndon B. Johnson took notice of these demonstrations and on March 17, 1965 he declared that all restrictions to voting that inhibited African Americans would be struck down. On March 21, 1965, a 3rd march was held which successfully made it to Montgomery.40 The intense crowds and actions of people in these demonstrations dramatized the issue of voting rights, which led to change in legislature. Homosexuals in California held a comparable demonstration in San Francisco on June 25, 1978 known as the Gay Freedom Day Parade. At the time of this parade, the Gay Rights Movement was very active in San Francisco due to the election of Harvey Milk. The most prominent issue at the moment was Proposition 6. Proposition 6 was a controversial legislature introduced by California senator John Briggs which would eliminate all homosexuals from teaching positions in public schools.41 The parade dramatized the issue of this Proposition by demonstrating large support of the homosexual community, and that this Proposition was 37 Carson, 2003 Carson, 2003 39 Carson, 2003 40 Carson, 2003 41 Hirshman, 2012 38 unjustly. The parade, composed floats and thousands of marchers, began in The Castro and continued down Market Street where it ended at the San Francisco Civic Center, one block from San Francisco City Hall.42 At the conclusion of the parade, Harvey Milk gave a monumental speech in which he called upon the federal government, President Jimmy Carter, and the people of California to not support Proposition 6.43 Milk also called upon homosexuals to come out of the closet as to eliminate stereotypes and prejudice towards them. This demonstration had great influence. On the day of the parade, John Briggs agreed to have a public debate with Harvey Milk about the Proposition.44 This debate occurred on September 6, 1978, and it exposed flawed logic in the proposition.45 Also, later that year, Jimmy Carter openly opposed Proposition 6 in a public appearance.46 The effects and dramatizations of the 1978 Gay Freedom Parade were very significant and contributed to the voting down of Proposition 647. Another way in which issues were dramatized in the African American Civil Rights movement was the mass arrest of children at Birmingham, AL, protests. Birmingham was Alabama’s largest city, thus it was a target for the SCLC to end segregation. Organized by a Birmingham Minister named Fred Shuttlesworth and the SCLC, the first protests occurred on April 3, 1963.48 The protests utilized in Birmingham were primarily marches. Many people gathered at various churches in Birmingham and marched to Birmingham City Hall. The goal of these marches was to get as many people arrested as possible, thus bringing national attention to the issues of segregation in Birmingham. Under the lash of Birmingham Public Safety Commissioner Theophilus Eugene "Bull" Connor, this would not be a problem. Connor was “40000 join peaceful,” 1977 SF Pride, 2012 44 Van Sant, 2008 45 “Harvey milk meets, 1978 46 Epstein, 1984 47 Van Sant, 2008 48 Carson, 2003 42 43 notorious for brutal arrests. However, it was hard to get many people to participate in these protests because most adults in Birmingham could not afford the financial toll of being arrested.49 This issue was solved by the SCLC by allowing children to participate in the marches. There were thousands of children willing to participate and the arresting of minors would draw enormous public attention. On May 2, 1963, hundreds of children marched in Birmingham.50 Connor ordered the mass arrests of the children; so many were taken into custody that when the police ran out of paddy wagons, school buses were used to haul them to jail. On May 3, 1963, hundreds more children marched in Birmingham, but instead of arresting them, Connor had them attacked with fire houses and attack dogs because all the jails were full.51 This animosity and violence drew enormous media attention and let the entire world know about the injustice in Birmingham. President John F. Kennedy even remarked at a press conference that he felt for the victims in Birmingham.52 By the end of the Birmingham protests, segregation was eradicated, and the arrest of children played a significant role in this victory. Using arrests to dramatize issues was also used in the Gay Rights Movement to repeal California Sodomy Laws. Repealing of sodomy laws was the primary task of activist Troy Perry. Perry was the founder and president of the Metropolitan Community Church (MCC).53 The MCC was a powerful Christian church that served the homosexual community with a message that their lifestyle was not a crime against God. By 1970 the MCC had thousands of members and chapters in San Francisco, Los Angeles, San Diego, Chicago, and Honolulu.54 In partnership with the Gay Liberation Front (GLF), Perry organized a demonstration in which lawyers of the 49 Carson, 2003 Sargent, 2004 51 Carson, 2003 52 Carson, 2003 53 Hirshman, 2012 54 Hirshman, 2012 50 GLF performed a citizen’s arrest on 3 couples for admitting to having anal sex in May 1974.55 The couples were a lesbian, heterosexual, and gay couple which included Troy Perry. The couples were taken to the Los Angeles district attorney who declared that the government had no right to intervene in the private lives of consenting adults.56 He thus avoided prosecuting the powerful Troy Perry which would have been a major media blunder. This declaration started the momentum for the California Sodomy Laws to be repealed in 1975.57 In both cases of the African American Civil Rights Movement and the Gay Rights Movement, arrests were used to dramatize issues and bring media attention, which successfully brought social change. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Harvey Milk An essential aspect of any movement is the work of its leaders. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. is practically the face of the African American Civil Rights Movement. He was the leader of the Montgomery Bus Boycott, president of the SCLC and a speaker at the African American March on Washington.58 There are many characteristics of King’s leadership but one of the most significant is his opposition to violence. A powerful example of this occurred during the Montgomery Bus Boycott. On January 30, 1956, while King was conducting a meeting at Abernathy’s Church, his home was bombed. It is believed to have been retaliation by the Ku Klux Klan, a white supremacy terrorist group. The night of the bombing, a crowd of people gathered outside King’s home wielding weapons and preparing for a riot, but in response, King talked down the crowd by telling them violence was not the way to respond.59 This is but one example in which King prevented violence and maintained peace. Harvey Milk played an extremely similar role in calming the homosexuals of San 55 Hirshman, 2012 Hirshman, 2012 57 Adam, 1995 58 D’Emilio, 1979 59 McKissack, 1991 56 Francisco. On June 7, 1977 a vote was held in Miami-Dade County, FL to repeal the county’s Gay Rights Ordinance which protected homosexuals from persecution.60 The action to put this issue on the ballot was largely perpetrated by Anita Bryant, a Florida Orange Juice spokesperson who became a public figure against Gay Rights.61 To the homosexuals of the nation, especially those in San Francisco, this was a major attack. The ordinance was successfully repealed which caused the homosexuals of The Castro to flood into the streets.62 As the crowd grew larger and more aggressive it was apparent that a riot was to ensue. In order to prevent this violence, Milk received police permission to march the crowd to San Francisco City Hall. Milk told the crowd that instead of releasing their anger with a riot they should march the streets. By marching the crowd, instead of letting their aggression spill out in The Castro, Milk avoided senseless violence which could have set back the Gay Rights Movement. Both King and Milk used their persuasion skills to prevent violence, strategies extremely essential to their respective movements. Tragically, King and Milk were both assassinated. Ironically, the deaths of these peaceful leaders both led to extreme riots. At the time of his death, King was in Memphis, TN helping to protest for the rights of sanitation workers. On the evening of April 4, 1968 King was leaving the Lorraine Motel to have dinner with a Memphis minister when he was shot in the head on the balcony.63 King was shot by James Earl Ray, an escape convict from the Missouri State Penitentiary.64 King was rushed to the hospital but proclaimed dead that night. By the end of the following day, riots had begun in major U.S. cities such as Chicago, IL, Newark, NJ, Los 60 Adam, 1995 Hirshman, 2012 62 Van Sant, 2008 63 US National Archives, 1979 64 US National Archives, 1979 61 Angeles, CA and Birmingham, AL.65 The riots did not last for longer than 2 days at most but they still demonstrated public outcry for the death of King. Harvey Milk was killed by fellow San Francisco supervisor Dan White along with Mayor George Moscone on November 27, 1978 at San Francisco City Hall.66 Dan White had recently resigned from his position but wanted his job back.67 However, he was not going to be reinstated which led to his killing of Moscone and Milk. It was Moscone’s responsibility to reappoint someone else to the Board of Supervisors and White had been a political enemy to Milk. Following the assassination a candlelight march was held in San Francisco, riots did not ensue until 5 months later when White was only convicted of voluntary manslaughter and sentenced to 7 years in prison.68 White’s lawyers claimed that White’s diet of junk food led to his insanity, and he was thus not responsible for the murders; this would later be called be “Twinkie” Defense.69 Public anger for the meager sentence culminated in the White Night Riots which led to destruction in much of the downtown San Francisco area, especially around city hall. These riots were the largest in the Gay Rights Movement. Despite the peaceful leadership of King and Milk, both of their assassinations led to riots and mass destruction. Conclusion The African American Civil Rights Movement and Gay Rights Movement may be different but the events and outcomes compare in multiple ways. There were multiple supervising organizations for the movements which focused on national and local levels. Some overarching organizations were the SCLC, Taverns Guild, and Mattachine Society, all of which held voting registration drives. Some focused on local levels were the MIA and SIR. In both 65 Coates, 2014 Epstein, 1984 67 Epstein, 1984 68 Epstein, 1984 69 Van Sant, 2008 66 movements, boycotts were used to establish their groups as influential and create change. The Montgomery Bus Boycott was a large victory for African Americans and ended public bus segregation. The Coors Beer Boycott demonstrated the influence of the homosexual population in San Francisco and gave them allies with labor unions. Dramatization of issues and goals were also prevalent. The Selma to Montgomery marches and Gay Freedom Day parade were demonstrations of support for African American Civil Rights and Gay Rights which caught attention of the government. Arrests were used in Birmingham, AL when children were arrested for marching and in Los Angeles, CA when 3 couples were arrested for having anal sex. These mass arrests both led to social change in which Birmingham segregation ended and California repealed its Sodomy Laws. Finally, the actions of movements’ leaders Martin Luther King Jr. and Harvey Milk compare in that they both prevented violence by talking down aggressive crowds and that their followers responded with riots to their assassinations. This comparison of events in the African American Civil Rights Movement demonstrates that ending prejudice is most effective in this specific way, and that bigotry exists in all places, and in all forms. In this example more than ever it is apparent that history does repeat itself. Works Cited Interviews: Leeth, E. (2014, July 14). Interview by P. Healy [Personal Interview]., Bradenton, FL. Pamela, M. (2014, July 04). Interview by P. Healy [Personal Interview]., Seminole, FL. Newspaper Articles: Cops invade homosexual benefit ball. (1965, January 02). San Francisco Chronicle 40000 join peaceful march for homosexual rights. (1977, June 27). New York Times Newscasts: Harvey milk meets john briggs [Television series episode]. (1978). In KPIX-TV Special Report. San Francisco, CA: CBS. Retrieved from https://diva.sfsu.edu/collections/sfbatv/bundles/190667 Books: Adam, B. (1995). The rise of a gay and lesbian movement. New York, NY: Twayne Publishers. Alensas, L. (2008). Gay america. New York, NY: HNA. Bullough, V. (1997). Before stonewall: Activists for gay and lesbian rights in historical context. Binghamton, NY: Harrington Park Press. Carrier, J. (2004). A traveler's guide to the civil rights movement. Orlando, FL: Harcourt, Inc. Carson, C. (2003). Civil rights chronicle: The african-american struggle for freedom. Lincolnwood, IL: Publications International. D'Emilio, J. (1979). The civil rights struggle: Leaders in profile. New York, NY: Facts on File. Hirshman, L. (2012). Victory: the triumphant gay revolution. New York, NY: Harper Collins Publishers. McKissack, P. (1991). The civil rights movement in america. (2nd ed.). Childrens Press. Russell, P. (1995). The gay 100. Secaucus, NJ: Citadel Press. Sargent, F. (2004). The civil rights revolution. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc. Winters, P. (2000). The civil rights movement. San Diego, CA: Greenhaven Press, Inc. Documentaries: Epstein, R. (Director) (1984). The times of harvey milk [DVD]. Van Sant, G. (Director) (2008). Milk [DVD]. Websites: Barron, C. (2013, February 01). Rosa parks’s little protest led to big change. Retrieved from http://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/kidspost/rosa-parkss-little-protest-led-to-bigchange/2013/02/01/a2cc0746-5e5b-11e2-a389-ee565c81c565_story.html Coates, J. (2014). Riots follow killing of martin luther king jr.. Retrieved from http://www.chicagotribune.com/news/nationworld/politics/chi-chicagodays-kingriotsstory-story.html SF Pride. (2012, September 04). Come out with joy, speak out for justice. Retrieved from http://www.sfpride.org/heritage/1978.html Steele, K. (2010, February 21). Our history sclc national. Retrieved from http://sclcnational.org/our-history/ US National Archives. (1979). Findings on mlk assasination. Retrieved from http://www.archives.gov/research/jfk/select-committee-report/part-2a.html