Money, Banking And The Financial Sector

advertisement

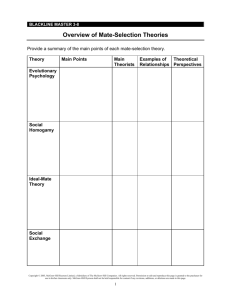

Money, Banking and the Financial Sector Chapter 13 © 2003 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. 13 - 2 Laugher Curve A central banker walks into a pizzeria to order a pizza. When the pizza is done, he goes up to the counter to get it. © 2003 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. 13 - 3 Laugher Curve The clerk asks him: “Should I cut it into six pieces or eight pieces?” The central banker replies: “I’m feeling rather hungry right now. You’d better cut it into eight pieces.” © 2003 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. 13 - 4 Introduction Real goods and services are exchanged in the real sector of the economy. For every real transaction, there is a financial transaction that mirrors it. © 2003 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. 13 - 5 Introduction The financial sector is central to almost all macroeconomic debates because behind every real transaction, there is a financial transaction that mirrors it. © 2003 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. 13 - 6 Introduction All trade in the goods market involves both the real sector and the financial sector. © 2003 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. 13 - 7 Why Is the Financial Sector So Important to Macro? The financial sector is important to macroeconomics because of its role in channeling savings back into the circular flow. © 2003 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. 13 - 8 Why Is the Financial Sector So Important to Macro? Savings are returned to the circular flow in the form of consumer loans, business loans, and loans to government. © 2003 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. 13 - 9 Why Is the Financial Sector So Important to Macro? Savings are channeled into the financial sector when individuals buy financial assets such as stocks or bonds and back into the spending stream as investment. © 2003 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. 13 - 10 Why Is the Financial Sector So Important to Macro? For every financial asset there is a corresponding financial liability. Financial assets such as stocks and bonds, are obligations or financial liabilities of the issuer. © 2003 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. 13 - 11 The Financial Sector as a Conduit for Savings, Fig. 13-1, p 307 Pension funds CDs Savings deposits Chequing deposits Stocks Bonds Government Securities Life insurance Outflow from spending stream Inflow from spending stream Gov’t Households Corporations Gov’t Saving Loans Financial sector Households Corporations Large business loans Small business loans Venture capital loans Construction loans Investment loans © 2003 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. 13 - 12 The Role of Interest Rates in the Financial Sector While price is the mechanism that balances supply and demand in the real sector, interest rates do the same in the financial sector. © 2003 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. 13 - 13 The Role of Interest Rates in the Financial Sector The interest rate is the price paid for use of a financial asset. Bonds are promises to pay a certain amount plus interest in the future. © 2003 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. 13 - 14 The Role of Interest Rates in the Financial Sector When financial assets such as bond make fixed interest payments, the price of the financial asset is determined by the market interest rate. © 2003 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. 13 - 15 The Role of Interest Rates in the Financial Sector When interest rates rise, the value of the flow of payments from fixed-interestrate bonds goes down because more can be earned on new bonds that pay the new, higher interest. © 2003 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. 13 - 16 The Role of Interest Rates in the Financial Sector As the market interest rates go up, price of the bond goes down. As the market interest rates go down, the price of the bond goes up. © 2003 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. 13 - 17 Savings That Escape the Circular Flow Some economists believe that the interest rate does not balance the demand and supply of savings, causing macroeconomic problems. © 2003 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. 13 - 18 Savings That Escape the Circular Flow In order to make sense of the problem, macroeconomics divides the flows into two types of financial assets. © 2003 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. 13 - 19 Savings That Escape the Circular Flow In order to make sense of the problem, macroeconomics divides the flows into two types of financial assets. © 2003 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. 13 - 20 Savings That Escape the Circular Flow The first type include bonds and loans which work their way into the system. The second type, money held by individuals, is not necessarily assumed to work its way back into the flow. © 2003 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. 13 - 21 The Definition and Functions of Money Money is a highly liquid financial asset. To be liquid means to be easily changeable into another asset or good. Social customs and standard practices are central to the liquidity of money. © 2003 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. 13 - 22 The Definition and Functions of Money Money is generally accepted in exchange for other goods. Money is used as a reference in valuing other goods. Money can be stored as wealth. © 2003 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. 13 - 23 The Canadian Central Bank: Bank of Canada Bank of Canada – The Canadian central bank whose liabilities (bank notes) serve as cash in Canada. © 2003 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. 13 - 24 Bank of Canada A bank is a financial institution whose primary function is holding money for, and lending money to, individuals and firms. Individuals’ deposits in savings and chequing accounts serve the same function as does currency and are also considered money. © 2003 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. 13 - 25 Functions of Money Money is a medium of exchange. Money is a unit of account. Money is a store of wealth. © 2003 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. 13 - 26 Money As a Medium of Exchange Without money, we would have to barter—a direct exchange of goods and services. Money facilitates exchange by reducing the cost of trading. © 2003 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. 13 - 27 Money As a Medium of Exchange Money does not have to have any inherent value to function as a medium of exchange. All that is necessary is that everyone believes that other people will exchange it for their goods. © 2003 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. 13 - 28 Money As a Medium of Exchange The Bank of Canada’s job is to not issue too much or too little money. If there is too much money, compared to the goods and services at existing prices, the goods and services will sell out, or the prices will rise. © 2003 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. 13 - 29 Money As a Medium of Exchange If there is too little money, compared to the goods and services at existing prices, there will be a shortage of money and people will have to resort to barter, or prices will fall. © 2003 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. 13 - 30 Money As a Unit of Account Money prices are actually relative prices. A single unit of account saves our limited memories and helps us make reasonable decisions based on relative costs. © 2003 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. 13 - 31 Money As a Unit of Account Money is a useful unit of account only as long as its value relative to other prices does not change too quickly. In a hyperinflation, all prices rise so much that our frame of reference is lost and money loses its usefulness as a unit of account. © 2003 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. 13 - 32 Money as a Store of Wealth Money is a financial asset. It is simply a government bond that pays no interest. © 2003 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. 13 - 33 Money as a Store of Wealth As long as money is serving as a medium of exchange, it automatically also serves as a store of wealth. © 2003 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. 13 - 34 Money as a Store of Wealth Money’s usefulness as a store of wealth also depends upon how well it maintains its value. Hyperinflations destroy money’s usefulness as a store of value. © 2003 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. 13 - 35 Money as a Store of Wealth Our ability to spend money for goods makes it worthwhile to hold money even though it does not pay interest. © 2003 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. 13 - 36 Alternative Measures of Money Since it is difficult to define money unambiguously, economists have defined different measures of money. They are called M1, M2 and M3, M1+, M2+ and M2++. © 2003 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. 13 - 37 Alternative Measures of Money: M1 M1 consists of currency in circulation and chequing account balances at chartered banks. Chequing account deposits are included in all definitions of money. © 2003 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. 13 - 38 Alternative Measures of Money: M2 M2 is made up of M1 plus personal savings deposits, and non personal notice deposits (that can be withdrawn only after prior notice) held at chartered banks. Time deposits are also called certificates of deposit (CDs), or term deposits. © 2003 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. 13 - 39 Alternative Measures of Money: M2 The money in savings accounts is counted as money because it is readily available. © 2003 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. 13 - 40 Alternative Measures of Money: M2 All M2 components are highly liquid and play an important role in providing reserves and lending capacity for chartered banks. © 2003 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. 13 - 41 Alternative Measures of Money: M2 The M2 definition is important because economic research has shown that the M2 definition often most closely correlates with the price level and economic activity. © 2003 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. 13 - 42 Beyond M2: “The Pluses” Numerous financial assets also have some attributes of money. That is why they are included in some measures of money. There are measures for M3, M1+, M2+ and beyond. © 2003 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. 13 - 43 Beyond M2: “The Pluses” The broadest measure is M2++. It includes almost all assets that can be turned into cash on short notice. Broader concepts of asset liquidity have gained greater appeal than the measures of money, because money measures have been rapidly changing. © 2003 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. 13 - 44 Beyond M2: “The Pluses” M1, M2 and M3 measures only include deposits held at chartered banks. Measures containing a “+” also include deposits at other financial institutions (near banks). © 2003 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. 13 - 45 Components of M2 and M1, Fig . 13-2, p 313 © 2003 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. 13 - 46 Measures of Money in Canada: M1, M2 and M2+, Fig. 13-3, p 314 © 2003 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. 13 - 47 Distinguishing Between Money and Credit Credit card balances cannot be money since they are assets of a bank. In a sense, they are the opposite of money. © 2003 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. 13 - 48 Distinguishing Between Money and Credit Credit cards are prearranged loans. Credit cards affect the amount of money people hold. Generally, credit card holders carry less cash. © 2003 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. 13 - 49 Banks and the Creation of Money Banks are both borrowers and lenders. Banks take in deposits and use the money they borrow to make loans to others. Banks make a profit by charging a higher interest on the money they lend out than they pay for the money they borrow. © 2003 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. 13 - 50 Banks and the Creation of Money Banks can be analyzed from the perspective of asset management and liability management. © 2003 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. 13 - 51 Banks and the Creation of Money Asset management is how a bank handles its loans and other assets. Liability management how a bank attracts deposits and how it pays for them. © 2003 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. 13 - 52 How Banks Create Money Banks create money because a bank’s liabilities are defined as money. When a bank incurs liabilities it creates money. © 2003 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. 13 - 53 How Banks Create Money When a bank places the proceeds of a loan it makes to you in your chequing account, it is creating money. © 2003 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. 13 - 54 The First Step in the Creation of Money The Bank of Canada creates money by simply printing currency and exchanging it for bonds. Currency is a financial asset to the bearer and a liability to the Bank of Canada. © 2003 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. 13 - 55 The Second Step in the Creation of Money The bearer deposits the currency in a chequing account at the bank. The bank holds your money and keeps track of it until you write a cheque. © 2003 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. 13 - 56 Banking and Goldsmiths In the past, gold was used as payment for goods and services. But gold is heavy and the likelihood of being robbed was great. © 2003 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. 13 - 57 From Gold to Gold Receipts It was safer to leave gold with a goldsmith who gave you a receipt. The receipt could be exchanged for gold whenever you needed gold. © 2003 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. 13 - 58 From Gold to Gold Receipts People soon began using the receipts as money since they knew the receipts were backed 100 percent by gold. At this point, there were two forms of money – gold and gold receipts. © 2003 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. 13 - 59 The Third Step in the Creation of Money Little gold was redeemed, so the goldsmith began making loans by issuing more receipts than he had gold. He charged interest on the newly created gold receipts. © 2003 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. 13 - 60 The Third Step in the Creation of Money When the goldsmith began making loans by issuing more receipts than he had in gold, he created money. © 2003 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. 13 - 61 The Third Step in the Creation of Money The gold receipts were backed partly by gold and partly by people’s trust that the goldsmith would pay off in gold on demand. © 2003 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. 13 - 62 The Third Step in the Creation of Money The goldsmith soon realized that he could make more money in interest than he could earn in goldsmithing. The goldsmith had become a banker. © 2003 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. 13 - 63 Banking Is Profitable As the goldsmiths became wealthy, others started competing in offering to hold gold for free, or even offering to pay for the privilege of holding the public’s gold. © 2003 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. 13 - 64 Banking Is Profitable That is why most banks today are willing to hold the public’s money at no charge – they can lend it out and in the process, make profits. © 2003 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. 13 - 65 The Money Multiplier Banks lend a portion of their deposits keeping the balance as reserves. Reserves are cash and deposits a bank keeps on hand, or at the central bank, enough to manage the normal cash inflows and outflows. © 2003 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. 13 - 66 The Money Multiplier The desired reserve ratio is the ratio of reserves to total deposits. © 2003 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. 13 - 67 The Money Multiplier Banks used to be required by the Bank of Canada to hold a percentage of deposits - the required reserve ratio. If banks chose to hold an additional amount, this was called the excess reserve ratio. © 2003 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. 13 - 68 The Money Multiplier Banks “hold” currency for people and in return allow them to write checks for the amount they have on deposit at the bank. © 2003 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. 13 - 69 Determining How Many Demand Deposits Will Be Created To determine the total amount of deposits that will eventually be created, the original amount that is deposited is multiplied by 1/r, where r is the reserve ratio. © 2003 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. 13 - 70 Determining How Many Demand Deposits Will Be Created For an original deposit of $100 and a reserve ratio of 10 percent, the formula would be: 1/r = 1/0.10 = 10 10 X $100 = $1,000 © 2003 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. 13 - 71 Determining How Many Demand Deposits Will Be Created This means that $900 of new money was created ($1,000 -$100). © 2003 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. 13 - 72 Calculating the Money Multiplier The ratio 1/r is called the simple money multiplier. The simple money multiplier is the measure of the amount of money ultimately created per dollar deposited in the banking system, when people hold no currency. © 2003 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. 13 - 73 Calculating the Money Multiplier The higher the reserve ratio, the smaller the money multiplier, and the less money will be created. © 2003 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. 13 - 74 An Example of the Creation of Money The first 10 rounds of the money creation process is illustrated in the following table. Assume a deposit of $10,000 and a desired reserve ratio of 20 percent. © 2003 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. 13 - 75 An Example of the Creation of Money, Table 13-1, p 319 Bank Gets Initial deposit Second stage Third stage Fourth stage Fifth stage Sixth stage Seventh stage All other stages TOTAL 10,000 8,000 6,400 5,120 4,096 3,277 2,621 10,486 50,000 Bank Keeps (Reserve Ratio: 20%) 2,000 1,600 1,280 1,024 819 656 524 2,097 10,000 Bank Loans (80%) = Person Borrows 8,000 6,400 5,120 4,096 3,277 2,621 2,097 8,389 40,000 © 2003 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. 13 - 76 An Example of the Creation of Money If banks keep excess reserves for safety reasons, the money multiplier decreases. © 2003 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. 13 - 77 Calculating the Approximate Real-World Money Multiplier The approximate real-world money multiplier in the economy is: 1/(r +c) r = the percentage of deposits banks desire to hold in reserve c = the ratio of money people hold in cash to the money they hold as deposits © 2003 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. 13 - 78 Calculating the Approximate Real-World Money Multiplier Assume banks keep 10 percent in reserve and the ratio of individuals’ cash holdings to their deposits is 25 percent. © 2003 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. 13 - 79 Calculating the Approximate Real-World Money Multiplier The approximate real-world money multiplier is: 1/(0.1 +0.25) = 1/0.35 = 2.9 © 2003 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. 13 - 80 Faith as the Backing of Our Money Supply Promises to pay underlie any financial system. All that backs the modern money supply are promises by borrowers to repay their loans and government guarantees that banks’ liabilities to depositors will be met. © 2003 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. 13 - 81 Regulation of Banks and the Financial Sector The banking system’s ability to create money presents potential problems. © 2003 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. 13 - 82 Financial Panics The financial history of the world is filled with stories of financial upheavals and monetary problems. In the 1800s, banks were allowed to issue their own notes, which often became worthless. © 2003 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. 13 - 83 Anatomy of a Financial Panic Financial systems are based on trust that expectations will be fulfilled. Banks borrow short and lend long, which means that if people lose faith in banks, the banks cannot keep their promises. © 2003 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. 13 - 84 Government Policy to Prevent Panic To prevent panics, various levels of government guarantee the obligations of many financial institutions. The Canada Deposit Insurance Corporation (CDIC) was created in 1967 to guarantee limited amounts of deposits at chartered banks and trust and mortgage loan companies. © 2003 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. 13 - 85 Government Policy to Prevent Panic Financial institutions pay a small premium for each dollar of deposit to the government-organized insurance company. That company puts the premium into a fund used to bail out banks experiencing a run on deposits. © 2003 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. 13 - 86 Government Policy to Prevent Panic These guarantees have two effects: They prevent the unwarranted fear that causes financial crises. They prevent warranted fears. © 2003 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. 13 - 87 The Benefits and Problems of Guarantees The fact that deposits are guaranteed does not serve to inspire banks to make certain deposits are covered by loans in the long run. © 2003 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. 13 - 88 Costly Failures of the 1980s and 1990s Since its inception, the CDIC has been called on to provide assistance to depositors in more than 20 failed financial institutions. In the late 70s and early 80s, a number of new institutions in Alberta and British Columbia faced difficult times when oil prices fell and economy went into recession. © 2003 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. 13 - 89 Costly Failures of the 1980s and 1990s In the 1990s the CDIC settled the claims of over a million depositors, most due to the collapse of Central Guaranty Trust Company. This put the CDIC in a difficult financial position, because the rates they had been charging for insurance were not enough to cover the losses. © 2003 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. Money, Banking and the Financial Sector End of Chapter 13