Lecture 2: Lessons from Past Financial Crises

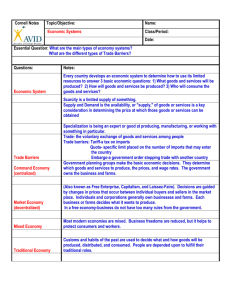

advertisement

Thorvaldur Gylfason Joint Vienna Institute Course on Macroeconomic Policies in Times of High Capital Mobility Vienna, Austria May 16–20, 2011 1. The Great Crash and its consequences 2. What is a systemic banking crisis? 3. Main origins of a crisis 4. From crisis recognition to crisis management 5. Theories of financial crises 6. Policy responses in financial crises 7. Banks and incentives 8. Twelve lessons from recent crisis The Great Depression 1929-39 produced a deep slump in output in the US and elsewhere, with dramatic consequences It also triggered reforms that reduced volatility in output, reducing the likelihood of another great crash Stabilization of output Regulation of banks and other financial institutions 0 2003 1999 1995 1991 1987 1983 1979 1975 1971 1967 1963 1959 1955 1951 1947 1943 1939 1935 1931 1927 1923 1919 1915 1911 1907 1903 1899 1895 1891 1887 1883 1879 1875 1871 Change in Canada’s per capita GDP from year to year 1871-2003 (%) 20 15 10 5 -5 -10 -15 -20 Source: Maddison (2003). Standard deviation of per capita GDP fell from 6.6% 1871-1945 to 2.3% 1947-2003 Yet per capita GDP growth remained virtually the same (2.1% vs. 2.2%) In postwar period, active stabilization was the norm plus careful federal rather than decentralized financial supervision Canada’s banks are universal, offering both commercial and investment banking services Even so, recent financial crisis passed Canada by Firewalls between commercial banking and investment banking were not in place in Canada 0 2003 1999 1995 1991 1987 1983 1979 1975 1971 1967 1963 1959 1955 1951 1947 1943 1939 1935 1931 1927 1923 1919 1915 1911 1907 1903 1899 1895 1891 1887 1883 1879 1875 1871 Change in US per capita GDP from year to year 1871-2003 (%) 20 15 10 5 -5 -10 -15 -20 -25 Source: Maddison (2003). Standard deviation of per capita GDP fell from 6.4% 1871-1945 to 2.4% 1947-2003 Yet per capita GDP growth remained virtually the same (2.3% vs. 2.1%) From the 1960s onward, active stabilization was the norm, as was federal as well as local financial supervision from 1933 onward Automatic stabilizers helped From 1870 to 1914, federal expenditures decreased from 5% of GDP to 2%, rising back to 5% by 1929 From 1945 to date, federal expenditures doubled from 10% of GDP to 20% 0 1831 1835 1839 1843 1847 1851 1855 1859 1863 1867 1871 1875 1879 1883 1887 1891 1895 1899 1903 1907 1911 1915 1919 1923 1927 1931 1935 1939 1943 1947 1951 1955 1959 1963 1967 1971 1975 1979 1983 1987 1991 1995 1999 2003 Change in UK per capita GDP from year to year 1871-2003 (%) 15 10 5 -5 -10 -15 Source: Maddison (2003). 0 1821 1826 1831 1836 1841 1846 1851 1856 1861 1866 1871 1876 1881 1886 1891 1896 1901 1906 1911 1916 1921 1926 1931 1936 1941 1946 1951 1956 1961 1966 1971 1976 1981 1986 1991 1996 2001 Change in French per capita GDP from year to year 1821-2003 (%) 50 40 30 20 10 -10 -20 Source: Maddison (2003). 10 0 1851 1855 1859 1863 1867 1871 1875 1879 1883 1887 1891 1895 1899 1903 1907 1911 1915 1919 1923 1927 1931 1935 1939 1943 1947 1951 1955 1959 1963 1967 1971 1975 1979 1983 1987 1991 1995 1999 2003 Change in German per capita GDP from year to year 1851-2003 (%) 20 Stefan Zweig (1942) Die Welt von Gestern -10 -20 -30 -40 -50 Source: Maddison (2003). 0 1821 1826 1831 1836 1841 1846 1851 1856 1861 1866 1871 1876 1881 1886 1891 1896 1901 1906 1911 1916 1921 1926 1931 1936 1941 1946 1951 1956 1961 1966 1971 1976 1981 1986 1991 1996 2001 Change in Swedish per capita GDP from year to year 1821-2003 (%) 10 5 -5 -10 -15 Source: Maddison (2003). The emergence of systemic banking crises has been associated with the liberalization of financial systems worldwide However, since the mid- to late 1990s a number of crises have been of unprecedented scale and consequences: Mexico 1994 Asian Crisis 1997-1998 Russia 1998, Ecuador 1998, Turkey 2001, Argentina and Uruguay 2002 US 2007 and its aftermath, including Iceland A banking crisis is systemic in nature if a loss of confidence in a substantial portion of the banking system is serious enough to generate significant adverse effects on the real economy The adverse effect on the real economy arises from disruptions to the payments system, to credit flows, and from the destruction of asset values Let’s look at some evidence which demonstrates the devastating nature of systemic crises Banking Problems Worldwide 1980-2002 Banking Crisis Significant Banking Problems No Significant Banking Problems/Insufficient Information 2001 150 1999 150 1997 5,000 1995 175 1993 175 1991 10,000 1989 200 1987 200 2000 1995 5,000 1990 10,000 1985 15,000 1980 15,000 1975 20,000 1970 20,000 In billions of local currency Finland Finland Indonesia Indonesia 150 150 600,000 600,000 Trend GDP Trend GDP GDP GDP 500,000 125 500,000 125 100 400,000 400,000 300,000 300,000 200,000 200,000 100,000 100,000 100 Source: IMF. 2001 1998 1995 1992 2000 1996 1992 1988 1984 50 1980 50 1989 75 1986 75 In billions of local currency Sweden Thailand Sweden Thailand 2,500 2,500 5,000 5,000 Trend GDP Trend GDP 2,250 2,250 GDP GDP 4,000 4,000 2,000 2,000 1,750 1,750 3,000 3,000 1,500 1,500 Source: IMF. 2001 1998 1995 1992 1989 1986 2001 1998 1,000 1995 1,000 1,000 1992 1,000 1989 1,250 1986 1,250 1983 2,000 1980 2,000 In billions of local currency Ecuador Ecuador 40,000 300 300 Trend GDP 35,000 GDP 275 275 30,000 250 250 225 225 200 200 10,000 175 175 5,000 150 150 25,000 20,000 Source: IMF. 2001 1999 1997 1995 1993 1991 1989 1987 2000 1995 15,000 In billions of local currency Korea Norway Korea Norway 600,000 600,000 1,250 1,250 Trend GDP Trend GDP GDP 500,000 500,000 400,000 1,125 1,125 GDP 1,000 1,000 875 875 750 750 625 625 500 500 400,000 Source: IMF. 2000 1996 1992 1988 1984 2001 1998 1995 100,000 1992 100,000 1989 200,000 1986 200,000 1980 300,000 1976 300,000 Need to distinguish between Causes and origin of a systemic crisis Trigger of the crisis Two views (or schools of thought) on origins of systemic crises Institutional failure leads to systemic crisis (classical view) Common exposure of financial sector to certain risks (endogenous cycle view) Some weak banks in the system, they stay above water until an external shock hits E.g., weak management, weak risk management systems, leading to balance sheet deficiencies, mismatches External shock can be anything (e.g., exchange rate shock, political crisis) Weak banks go under and, through contagion, pull others into problem zone Crisis become systemic Helps explain some crises, but not recent ones Source: Diamond and Dybvig (JPE, 1983) Systemic crisis follows from fact that banks have common exposures to macroeconomic risks Origin of scenario leading to endogenous cycle may differ from crisis to crisis, but … … pattern of response is similar I.e., how they get these common exposures Sources: Minsky (1982), Kindleberger (1996) Starting point: Economic conditions are considered favorably Risk evaluation is also favorable Access to credit is relaxed (subprime!) Endogenous or Profits go up self-feeding cycle Generalized state of euphoria Procyclical behavior Boom in asset prices and markets (amplification) Asset price bubble is forming Risk perceptions remain favorable But, imbalances start to emerge here and there … … and suddenly the situation goes into reverse E.g., through a change in mood The trigger can be anything E.g., change in mood, bad economic or political news, problems in neighboring countries, rumors Irrespective of origin, a crisis first emerges as a liquidity problem in one, some, or all banks Symptoms Bank goes repeatedly to interbank market Bank calls repeatedly upon lender-of-last resort and requests roll-over When the rumors spread, liquidity problems trigger deposit withdrawals (Asia) or credit lines that are being cut (Turkey) Liquidity problems are typically symptoms of underlying solvency problems Start of crisis often seems chaotic When a problem arises in one bank Is it an isolated case or will it spread? It takes time to assess situation and recognize that it is systemic Lack of preparedness on the authorities’ side Vested interests in delaying recognition, i.e., in avoiding fiscal costs as well as in accepting blame Indonesia 1997-present Chile 1981-1983 Thailand 1997-present Turkey 2000-present Korea 1997-present Ecuador 1998-2001 Mexico 1994-1995 Venezuela 1994-1995 Finland 1991-1993 Malaysia 1997-2001 Sweden 1991-1993 Gross Cost United States 1984-1991 Net Cost Norway 1987-1989 0 Sources: IFS, WEO and national authorities. 10 20 30 40 50 60 Liquidity If banks prove insolvent, and can’t repay liquidity support received earlier from central bank Deposit recapitalization Through the government insurance Government pay-outs as part of deposit insurance scheme or blanket guarantee Bank support If the government agrees to assist in recapitalizing the banks through some scheme Through restructuring of impaired assets A (government) asset management company buys impaired assets from banks in exchange for government bonds % of GDP Billions of USD Liquidity support provided by central bank, and taken over by budget 12 20 Recapitalization, including blanket guarantee 23 40 Purchase of NPLs and capital provided to asset management company 12 20 Interest cost (for the budget) 3 5 51 85 Total How long it takes politicians to recognize that they are face a crisis (+) … … and the time from the point of recognition to the time of action Quality of institutions (-) Level of corruption (+) Efficiency of judicial system (-) Restructuring approach (+/-) Strict vs. accommodating strategy (moral hazard) Types of incentives given during recapitalization Handling of impaired assets (+/-) Possible payback to government (+/-) Source: BIS (2009). Need for political leadership and coordination Managing a financial crisis Is a macro-undertaking with lots of microdecisions Involves tackling a number of politically contentious (vested interests), and often technically complex, issues Involves burden sharing and redistribution of wealth, with most parts of society affected Economic theories of financial crisis have tended to follow events Recent theories tend to reflect failure of markets to avert socially costly outcomes, with focus Different models correspond to specific country cases On problems in the markets themselves (particularly in asset markets) due to asymmetric information/agency problems, etc. On the role of economic policymakers (esp. central banks) that, in attempting to control credit creation to stabilize economy, unwittingly amplify boom/bust cycles On why markets do not always produce optimal solutions, see Freefall (2010) by Stiglitz The Origin of Financial Crisis (2008) by Cooper This Time Is Different (2009) by Rogoff and Reinhart Large deficits Current account deficits Government budget deficits Poor bank regulation Government guarantees (implicit or explicit), moral hazard Stock and composition of foreign debt Ratio of short-term liabilities to foreign reserves Mismatches Maturity mismatches (borrowing short, lending long) Currency mismatches (borrowing in foreign currency, lending in domestic currency) Increased inequality 5 0 -5 -10 -15 -20 -25 -30 -35 -40 Many crises are characterized by over-leveraging Increases vulnerability of debtors to external changes Usually, crises involve debt repayment difficulties for government, households, or corporate sector Debt servicing tends to become harder as crisis develops I.e., risk aversion, interest rate/exchange rate changes Foreign credit dries up, banks need to deleverage, value of collateral falls, trade credit becomes more difficult, etc. Does this help crisis prediction or crisis prevention? Extent of debt depends on interest rate/exchange rate What appears to be a manageable situation, proves unmanageable when variables change Debt levels change and so, too, does bank capital Net External Debt (% of GDP)* 1000 900 800 700 600 500 400 300 200 100 0 500 450 400 350 300 250 200 150 100 50 0 2004 2005 2007 2007 2008m 2008 *Excluding risk capital International Investment Position (% of GDP)* 1000 900 800 700 600 500 400 300 200 100 0 0 -20 -40 -60 -80 -100 -120 -140 -160 -180 2004 2005 2007 2007 2008 *Including risk capital Source: Union Bank of Switzerland 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 Switzerland Iceland 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 Months % of short-term debt 140 120 100 80 60 40 20 0 Increased inequality in distribution of US income and wealth during roaring 1920s Bubble conducive to higher incomes at top end of distribution, and vice versa Crisis of 2007 Subprime lending supported and made possible in part as compensation for increased inequality (Rajan) If so, inequality helped trigger crisis 45 40 35 30 25 20 15 10 5 0 Source: Internal Revenue Directorate. To restore confidence in a financial crisis, a policy program needs to be announced that is seen by creditors as comprehensive and fully financed First policy dilemma How to halt pressure on currency while bolstering domestic demand Should interest rates be temporarily raised? Should fiscal policy be tightened? Should capital controls be introduced? Second policy dilemma Should financial and firm-sector problems be tackled up front or left until later? Should banks be recapitalized with public funds? Perhaps no choice Solvency issues Forms of restructuring Should there be regulatory forbearance? Should public or private debts be restructured? Should government be involved in corporate restructuring? Pros and cons Increasing rates Helps external adjustment, reduces capital flight Deflationary when domestic demand is already in decline Places further stress on over-leveraged firms Middle class bonus Reducing rates Exerts greater pressure on exchange rate Obscures/postpones structural problems Credit supply constrained by banking problems “Mistake” Rationale for tighter fiscal policy Fiscal space in Iceland program 2008 Fiscal policy in Korea Difficulty of running a deficit Social programs in Asia Fiscal in Thailand IMF program 1997 policy in Argentina Size of haircut and extent of fiscal adjustment Preparing for post-crisis vs. getting through the crisis IMF’s conditional support for fiscal stimulus Short-run constraints on fiscal policy Time lags Credibility Type of fiscal action Longer-term issues of debt sustainability Difficulty of specifying a medium-term framework in the midst of a financial crisis Different speeds of recovery Impact on potential output Exit from fiscal stimulus Economics and politics Speculation Experience in Asian crisis of Malaysia and Hong Kong Malaysian speculation Capital flight Mahathir’s controls Hong Kong and the hedge fund conspiracy Transparency short selling and regulations against Mexico, Korea, Mexico, Thailand, Venezuela, Turkey, Venezuela, Argentina, Malaysia, Indonesia, Argentina, '93-95 '96-97 '81-83 '96-97 '87-90 '93-94 '92-94 '88-89 '86-89 '84-85 '82-83 12% of GDP 9% of GDP 18% of GDP 15% of GDP 11% of GDP 6% of GDP 10% of GDP 7% of GDP 10% of GDP 5% of GDP 4% of GDP 0 10 20 30 40 Billion dollars Source: Finance and Development, September 1999. 50 60 Growing acceptance of use of prudential regulations to limit systemic risk in banking system and, more generally, in national and international economy Countercyclical use of prudential ratios Liquidity ratios Differentiated by currency Reserve requirements Blanchard Differentiated by maturity Limitations Regulatory arbitrage Nonfinancial sector flows Recent cross-country evidence on effectiveness of capital controls Controls tend to have short-term impact, over time market participants find ways of circumventing Controls tend to change composition rather than overall volume of flows But, Ostry et al. (IMF Staff Position Note 10/04) find that “in the recent crisis the output decline of the countries that had maintained capital controls in the run-up to the crisis was lower than in other countries without capital controls” There are difficulties in empirical testing – how to measure capital control, what measures introduced at same time, what was counter-factual? Source: Global Financial Stability Report, IMF, April 2010. Financial globalization is often blamed for crises in emerging markets It has been suggested that emerging markets had dismantled capital controls too hastily, leaving themselves vulnerable More radically, some economists view unfettered capital flows as disruptive to global financial stability These economists call for capital controls and other curbs on capital flows (e.g., taxes) Others argue that increased openness to capital flows has proved essential for countries seeking to rise from lower-income to middleincome status Capital controls aim to reduce risks associated with excessive inflows or outflows Specific objectives may include Protecting a fragile banking system Avoiding quick reversals of short-term capital inflows following an adverse macroeconomic shock Reducing currency appreciation when faced with large inflows Stemming currency depreciation when faced with large outflows Inducing a shift from shorter- to longer-term inflows Administrative Outright bans, quantitative limits, approval procedures Market-based controls Dual or multiple exchange rate systems Explicit taxation of external financial transactions Indirect taxation E.g., unremunerated reserve requirement Distinction controls between Controls on inflows and controls on outflows Controls on different categories of capital inflows IMF (which has jurisdiction over current account, not capital account, restrictions) maintains detailed compilation of member countries’ capital account restrictions The information in the AREAER has been used to construct measures of financial openness based on a 1 (controlled) to 0 (liberalized) classification They show a trend toward greater financial openness during the 1990s But these measures provide only rough indications because they do not measure the intensity or effectiveness of capital controls (de jure versus de facto measures) Structural characteristics can sometimes be seen as root cause of a crisis In Korea, exceptionally high debt-equity ratios, low profitability of corporate sector, and increasing use of foreign currency bank loans to shore up finances in largest chaebol were viewed as indicative of structural problems, including lack of corporate governance, nonstandard accounting rules, directed lending, barriers to entry in various industries, failure of prudential regulation, etc. But many of these problems had been integral parts of the previously successful model of development IMF program 1997/98 contained many structural reforms to tackle these problems, some relevant, some dubious The criticism of these structural conditions was that their implementation prolonged the crisis; they were not immediately necessary. The counter-argument was that if changes had not been made at that time they would not have been introduced at all Only in the midst of a crisis could political support be mobilized to effect large institutional changes The case of Indonesia and crony capitalism Too many conditions, too political IMF programs and political stability Streamlining of structural conditionality Recent IMF programs and structural measures Linkages between structural measures and macroeconomic stability Testing banks for solvency How big is too big to fail? Closing banks in the absence of a deposit guarantee Indonesia Public ownership of private banks What conditions are needed? Purchasing “bad assets”– finding a price Proposals for regulatory reform in previous crises focused on widening coverage to prevent regulatory arbitrage and separating regulators and enhancing independence of supervision so as to reduce influence of governments and central banks The theme emerging from the global financial crisis is different in that prudential regulation was seen to pay insufficient attention not only to the risk management techniques of financial institutions but also to the build up of systemic risk Regulators need to look at a wider view of risk than from focusing on stability of financial institutions in isolation One proposal is that regulators focus rather on macro-prudential monitoring of the financial system as a whole While some calls have been made for changes that place regulators back within central banks, other recent proposals (in US House of Representatives, US Senate, UK, EU) call for the creation of councils, each comprising existing supervisory authorities and national central banks within their country (area), that would monitor the buildup of domestic financial systemic risk For the banks themselves, most authorities see the need for larger capital requirements, particularly for systemically important institutions, i.e., those with high degree of interconnectedness within the system However, consensus on the modalities of capital surcharges has not yet emerged Corporate programs debt restructuring and IMF Korea, Indonesia, more recently Latvia, Iceland Case for government intervention Three different approaches Case-by-case market-based approach Across-the-board with direct government involvement Intermediate approach with government financial incentives See Thomas Laryea: Approaches to Corporate Debt Restructuring in the Wake of Financial Crises, IMF Staff Position Note, January 2010 Government’s role in allocating the costs of a crisis Tax policies Social programs and redistribution during crisis Subsidies to financial institutions and enterprises Socializing losses and inter-generational effects Impact of government policies on future incentives Insurance and externalities of crisis mitigation IMF and allocation of costs of crisis between countries Incentive effects of “bailouts” Future crisis prediction and prevention Different causes in each new wave of crises There are limits to individual country risk analysis Cross-section econometric techniques Market Pressure Indices Mecagni et al. (2007) Index = -(FXt – FXtrend) – ln(NEERt/NEERt-1) + St – Kt Combines individual indicators FX (international reserves) NEER (nominal effective exchange rate) S (secondary market spread on sovereign bonds) K (net private capital flows as a ratio to GDP) All variables are standardized with their mean = 0 and their standard deviation = 1 The aim is to show deviations from normal levels of the components The start of a crisis is identified as the first of two consecutive quarters in which the value of the index is positive Financial Stress Indicators (IMF, 2008) rely on financial variables for 17 countries Equal-variance weighted average of seven variables 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. Banking-sector beta TED spread Inverted term spread Corporate spread Stock decline Time-varying stock volatility Time-varying real exchange rate volatility Financial stress if index is one standard deviation above its trend Typical Signal Indicators: Overvaluation of currency in real terms Financial liberalization Low output growth Fall in asset prices Weak exports High interest rates Rise in inequality See Kaminsky and Reinhart (1999) Type I and Type II Errors Both probability models and signal extraction models give too many false alarms Particularly difficult to get timing right In general, the empirical record of crisis prediction remains poor, particularly in out-of-sample tests Desirable elements to help prevent crises Sound macroeconomic policies Sound financial sector regulation and regular surveillance Sufficient international reserves Rigorous debt sustainability analysis International Monetary Fund. “What Happens During Recessions, Crunches and Busts?”, Stijn Claessens, M. Ayhan Kose and Marco E. Terrones, Working Paper WP/08/274, December 2008 International Monetary Fund. “The Role of Indicators in Guiding the Exit from Monetary and Financial Crisis Intervention Measures — Background Paper”, IMF Policy Paper, January 2010 International Monetary Fund. “Lessons and Policy Implications from the Global Financial Crisis”, Stijn Claessens et al., Working Paper WP/10/44, February 2010 Paul Volcker, Chairman of the Fed 1979-87, said 8 December 2009 at a conference organized by the Wall Street Journal: “I wish someone would give me one shred of neutral evidence that financial innovation has led to economic growth – one shred of evidence.” He added that in the U.S. the share of financial services in value added had risen from 2% to 6.5%, and then asked: “Is that a reflection of your financial innovation, or just a reflection of what you’re paid?” “The Best Way to Rob a Bank is to Own One” 1. 2. 3. 4. When a senior officer deliberately causes bad loans to be made he does not defraud himself He defrauds the bank’s creditors and shareholders, as a means of optimizing fictional accounting income It pays to seek out bad loans because only those who have no intention of repaying are willing to offer the high loan fees and interest required Grow really fast Make really bad loans at higher yields Pile up debts Put aside pitifully low loss reserves “The Best Way to Rob a Bank is to Own One” 1. 2. 3. 4. When a senior officer deliberately causes bad loans to be made he does not defraud himself He defrauds the bank’s creditors and shareholders, as a means of optimizing fictional accounting income It pays to seek out bad loans because only those who have no intention of repaying are willing to offer the high loan fees and interest required Grow really fast Make really bad loans at higher yields Pile up debts Put aside pitifully low loss reserves 1. Need legal protection against predatory lending because of asymmetric information Like laws against quack doctors, same logic Patients know less about health problems than doctors, so we have legal protection against medical malpractice Same applies to some bank customers vs. bankers, especially in connection with complex financial deals 2. Do not let rating agencies be paid by the banks Fundamental conflict of interest Also, prevent accountants from cooking the books 3. Need more effective regulation of banks and other financial institutions Work in progress, Paul Volcker in charge 4. Read the warning signals Four rules, or stories The Aliber Rule Count the cranes! The Giudotti-Greenspan Rule Do not allow gross foreign reserves held by the Central Bank to fall below the short-term foreign debts of the domestic banking system Failure to respect this rule amounts to an open invitation to speculators to attack the currency The Overvaluation Rule Sooner or later, an overvalued currency will fall The Distribution Rule • The distribution of income matters 45 40 35 30 25 20 15 10 5 0 Source: Internal Revenue Directorate. 5. Do not let banks outgrow Central Bank’s ability to stand behind them as lender – or borrower – of last resort 6. Do not allow banks to operate branches abroad rather than subsidiaries, thus exposing domestic deposit insurance schemes to foreign obligations Without having been told about it, Iceland suddenly found itself held responsible for the moneys kept in Landsbanki by 300.000 British depositors and 100.000 Dutch depositors May violate law against breach of trust 7. Central banks should not accept rapid credit growth subject to keeping inflation low As did the Fed under Alan Greenspan and the Central Bank of Iceland They must restrain other manifestations of latent inflation, especially asset bubbles and large external deficits Put differently, they must distinguish between “good” (well-based, sustainable) growth and “bad” (asset-bubble-plus-debt-financed) growth 8. Erect firewalls between banking and politics Corrupt privatization does not condemn privatization, it condemns corruption 9. When things go wrong, hold those responsible accountable by law, or at least try to uncover the truth: Do not cover up In Iceland, there have been vocal demands for an International Commission of Enquiry, a Truth and Reconciliation Committee of sorts If history is not correctly recorded if only for learning purposes, it is more likely to repeat itself Public – and outside world! – must know National Transport Safety Board investigates every civilaviation crash in United States; same in Europe 10. When banks collapse and assets are wiped out, protect the real economy by a massive monetary or fiscal stimulus Think outside the box: put old religion about monetary restraint and fiscal prudence on ice Always remember: a financial crisis, painful though it may be, typically wipes out only a small fraction of national wealth Physical capital (typically 3 or 4 times GDP) and human capital (typically 5 or 6 times physical capital) dwarf financial capital (typically less than GDP) So, financial capital typically constitutes one fifteenth or one twenty-fifth of total national wealth, or less National wealth Human capital Physical capital Financial capital 11. Shared conditionality needs to become more common As when the Nordic countries providing nearly a half of the $5 billion needed to keep Iceland afloat imposed specific conditions on top of the IMF’s conditions This may come up again elsewhere E.g., in Greece now that the EU and the IMF have been called on to support Greece together For this, clear and transparent rules tailored to such situations ought to be put in place 12. Do not jump to conclusions and do not throw out the baby with the bathwater Since the collapse of communism, a mixed market economy has been the only game in town To many, the current financial crisis has dealt a severe blow to the prestige of free markets and liberalism, with banks having to be propped up temporarily by governments, even nationalized Even so, it remains true as a general rule that banking and politics are not a good mix But private banks clearly need proper regulation because of their ability to inflict severe damage on innocent bystanders Do not reject economic, and legal, help from abroad