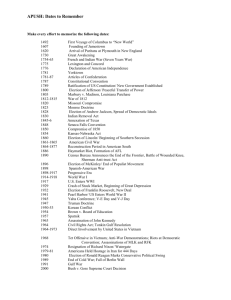

BASED ON NACHURA'S OUTLINE REVIEWER IN POLITICAL LAW

advertisement