Frogs - University of Warwick

advertisement

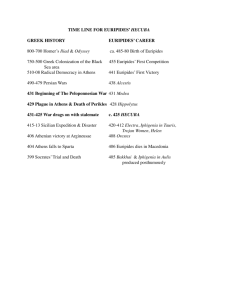

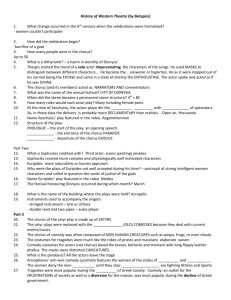

Frogs EN302: European Theatre Comedy • kômôidia, ‘revelsong’ • ritual celebration, including mockery • introduced into the City Dionysia around 486 BC • incorporated into the midwinter festival of the Lenaea around 440 BC ‘Old’ Comedy • Mocked public figures • Parodied well-known myths • Physically grotesque: • distorted masks (often caricatures) • padded bellies and buttocks • large dangling leather phalluses ‘Old’ Comedy • Formal elements of Attic comedy: • Prologos • Parados • Agon • Parabasis • Episodes • Exodos (also Kômos, i.e. revels) Aristotle (Poetics, c. 335-22 BC): • ‘Comedy is, as we have said, an imitation of characters of a lower type, - not, however, in the full sense of the word bad; for the ludicrous is merely a subdivision of the ugly. It may be defined as a defect or ugliness which is not painful or destructive. Thus, for example, the comic mask is ugly and distorted, but does not cause pain.’ (Palmer 1984: 27) Comic actors Statuettes of comic actors, late 5thc.- early 4th c. BC, New York Metropolitan Museum of Art Comic actors Statuettes of comic actors, late 5thc.- early 4th c. BC, New York Metropolitan Museum of Art Comic actors Statuettes of comic actors, late 5thc.- early 4th c. BC, New York Metropolitan Museum of Art Comic actors Statuettes of comic actors, late 5thc.- early 4th c. BC, New York Metropolitan Museum of Art Aristophanes (c. 446 BC – c. 386 BC) • The only comic dramatist of the period whose plays have survived (11 of around 30-40 plays). • Won first prize at least three times (probably more): • Acharnians (425 BC), • Knights (424 BC) • Frogs (405 BC) • Attacked the powerful Athenian politician Cleon in numerous plays: Babylonians (426), Acharnians, Knights, and Wasps (422). Aristophanes alludes to Cleon’s lawsuit against him in Frogs. • Used drama to advocate peace with Sparta in Acharnians, Peace (421) and Lysistrata (411). • Frogs was performed as the Lenaea in 405 BC, where Aristophanes was not only awarded first prize, but also rewarded with a crown and an unusual opportunity to revive the play. Meta-Comedy in Frogs The play’s first line: XANTHIAS. How about one of the old gags, sir? I can always get a laugh with those. (p. 133) XANTHIAS. Do you mean to say that I've been lugging these props around but I'm not allowed to use them to get a laugh? That's what usually happens. Phrynichus, Lycis, Ameipsias – all the popular playwrights do it. The comic porter scene. There's one in every comedy. (p. 134) [All three of the comedians referred to here won first prizes] References to the audience Flattery: CHORUS. Here sit ten thousand men of sense, A most enlightened audience (p. 159) CHORUS. As for the audience, You're quite mistaken If you think subtle points Will not be taken. Such fears are vain, I vow – They've all got textbooks now – However high your brow, They'll not be shaken. (p. 176) Mockery/abuse: The audience are associated with the unsaved souls of the Underworld. DIONYSUS. Any sign of those murderers and perjurers he told us about? XANTHIAS. Use your eyes, sir. DIONYSUS. [looking towards the audience] Oh, yes, I see them now. (p. 145) Comedy as corrective? • Henri Bergson (‘Laughter’, 1900): • ‘Always rather humiliating for the one against whom it is directed, laughter is really and truly a kind of social “ragging”. … In laughter we always find an unavowed intention to humiliate, and consequently correct our neighbour.’ (1900: 148) • ‘…it is the business of laughter to suppress any separatist tendency… Its function is to intimidate by humiliating.’ (1900: 174, 188) • Topical, targeted satire, for example of the radical democrat Cleigenes as a corrupt ‘wash-house proprietor’ during the Parabasis (p. 161). • Does the play’s literary parody work in a similar way? Or is something else at work? Comedy as battle? • See the Chorus’s parodic description of the contest on pp. 165-6: Huge are the words that he wields, great compounds with rivets and bolts in, And epithets hewn from stone. Now it's the challenger's turn to reply to this verbal bombardment: Neatly each phrase he dissects, with intelligence subtle and keen; Harmless around him the adjectives tumble, as he ducks for cover And squeaks, 'It depends what you mean.’ (p. 166) Comedy as battle? • Sigmund Freud (Jokes and their Relation to the Unconscious, 1905): • ‘It is easy to divine the characteristic of jokes on which the difference in their hearers’ reaction to them depends. In the one case the joke is an end in itself and serves no particular aim, in the other case it does serve such an aim – it becomes tendentious. […] Where a joke is not an aim in itself – that is, where it is not an innocent one – there are only two purposes that it may serve, and these two can themselves be subsumed under a single heading. It is either a hostile joke (serving the purpose of aggressiveness, satire, or defence) or an obscene joke (serving the purpose of exposure).’ (1976: 132, 140) • Certainly both sexual innuendo and hostility feature heavily in this play Agon • Athenian cultural life was characterised by a spirit of competition. • The idea of a competition for first place between two great tragedians was, of course, rooted in reality. • Euripides and Sophocles had both died very shortly before the first performance of Frogs: in 406 and 405 BC respectively. • [N.B. The Bacchae had been written when Frogs was performed in early 405 BC, but was not performed until later that year.] • Aeschylus had died many years earlier, around 455 BC (thus not really in living memory). The contest • What are the criteria by which the contest is judged? • Chorus leader in Parabasis: We chorus folk two privileges prize: To amuse you, citizens, and to advise. (p. 160) AESCHYLUS. What are the qualities you look for in a good poet? EURIPIDES. Technical ability. A poet should also teach people how to be better citizens. (p. 172) The contest • ‘…and lost his little flask of oil’ • A puzzling sequence, in which Aeschylus parodies Euripides’ formulaic verse. But is he mocking: • Euripides’ plots? • Euripides’ use of metre? • Euripides’ choice of subject matter? The contest What are Aeschylus and Euripides used to represent? Aeschylus ‘Old’ ‘Might’ (Chorus, p. 168) Cultural authority Patriotism High-blown style, compound adjectives Masculine, heroic characters* Euripides ‘New’ ‘Wit’ (Chorus, p. 168) Radical experimentation Scepticism Style closer to everyday speech ‘Women, slaves, the master, the young maiden, the old crone – they all talked. […] It was democracy in action.’ (p. 170) *N.B. this does not quite tally with what survives of Aeschylus’ work, e.g. the choruses of Choephori and Eumenides. Euripides as radical Euripides’ admirers in the Underworld appear to be ‘cut-throats, highwaymen, murderers, burglars’ (p. 164). He was associated, both in Frogs and in life, with impiety: EURIPIDES. I pray to other gods. […] Hail Ether, my sustainer! Hail, Hinge of Tongue! Hail, Mind and sentient Nostrils! Inspire me with successful arguments. (p. 168) Euripides as radical Euripides was infamous in this respect for a line in Hippolytus: ‘My tongue did swear, but my heart is not under oath’. Frogs refers twice to this line: DIONYSUS. I defy you to find a genuine poet among the whole lot of them: one who can coin a memorable line. […] One who can produce something truly original, like [...] that bit about the tongue being allowed to perjure itself when the heart is not committed. (p. 137) EURIPIDES. Now remember the gods by whom you swore to take me home! Pick me, your friend! DIONYSUS. It was my tongue that swore… but I choose Aeschylus. (p. 189) Euripides as sceptic • ‘I taught them to observe, to discern, to interpret; to use spin, to massage the facts; to suspect the worst, to take nothing at face value… What I did was to teach the audience to use its brains, introduce a bit of logic into the drama. The public have learnt from me how to think, how to run their households, to ask ‘Why is this so? What do we mean by that?’’ (p. 171) • Sophistry: new movement in education, focus on rhetoric EURIPIDES. What about Persuasion? Doesn't that carry any weight? So beautifully phrased too. DIONYSUS. No, Persuasion is hollow. It has no substance of its own. (p. 186) Aeschylus as conservative patriot AESCHYLUS. Well, my Seven Against Thebes, for example. No one could see that play without wanting to go off at once and slaughter their enemies. […] I also put on my Persians: a telling lesson on the will to win. (p. 173) EURIPIDES. Did I invent the story of Phaedra? AESCHYLUS. Of course not, but the poet should keep quiet about them, not put them onstage as an example to everyone. Schoolboys have a master to teach them, adults have poets. We have a duty to see that what we teach them is right and proper. (p. 174) The question of Alcibiades • Alcibiades was in exile during this period (and had even served as military adviser to the Spartans), but was widely seen as the natural successor to the leader Pericles. CHORUS-LEADER. We don’t want the traitor who sides with the foe, We don't want the soldier who lets the fort go; The greedy official who'd even be willing To sell his own city just to make a killing. (p. 148) EURIPIDES [after some thought] I loathe a citizen who acts so fast To harm his country and yet helps her last, Who's deft at managing his own success, But useless when the city's in a mess. (p. 187) The question of Alcibiades AESCHYLUS. It is not very wise for city states To rear a lion cub within their gates; But if they do so, they will find it pays To tolerate its own peculiar ways. (p. 187) • In reality, the salvation of Athens (which Dionysus hopes to achieve by bringing back Aeschylus) was not achieved: within two years, Athens would be comprehensively defeated. The ending • Does the play show Aeschylus to be a deserving winner? • Ambiguity in the moments leading up to Dionysus’ judgement: DIONYSUS. You know, I like them both so much, I don't know how to judge between them. I don't want to make an enemy of either. One's so wise, and the other I just love. (p. 187) DIONYSUS. Honestly, I can't decide between them, when one speaks so discerningly, the other so distinctly. (p. 187) • The audience are thus encouraged to judge for themselves before Dionysus reveals his answer. The ending • Is Aeschylus’ win expressive of Athenian nostalgia for a bygone age? • Mark Griffith: • ‘Aeschylus stands for an idea (ideal) of the tragic art (and of democracy?) in which certain things are not spoken of or shown, and the audience need not confront the uncomfortable possibilities of female desire, class inequality, or divine ineptitude (or nonexistence), settling instead for an ideal of unity and community in which such divisions have been poetically transcended or obliterated.’ (2013: 218) Comedy as rebirth? • Why does Dionysus look to playwrights to save the city? • Northrop Frye (‘The Argument of Comedy’, 1948): • ‘…the action of the comedy begins in a world represented as a normal world, moves into the green world, goes into a metamorphosis there in which the comic resolution is achieved, and returns to the normal world.’ (Palmer 1984: 80) • Christopher Booker (The Seven Basic Plots, 2004): • ‘…we see a little world in which people have passed under a shadow of confusion, uncertainty and frustration, and are shut off from one another; …the confusion gets worse until the pressure of darkness is at its most acute and everyone is in a nightmarish tangle; … finally, with the coming to light of things not previously recognised, perceptions are dramatically changed. The shadows are dispelled, the situation is miraculously transformed and the little world is brought together in a state of joyful union.’ (2004: 150) • The battle of Arginusae (406 BC) • Context of ongoing Peloponnesian War • The Athenian navy defeated the Spartan navy in 406 BC, at a cost of a quarter of their fleet • Citizenship was offered to all slaves and foreigners who fought for Athens • Many existing Athenian citizens felt threatened and affronted • The eight victorious generals were blamed for these losses and sentenced to death, at the urging of radical democrat leaders including Cleophon and Theramenes (mentioned by name in Frogs) • Many Athenians subsequently doubted the ethics of this move The battle of Arginusae (406 BC) XANTHIAS. Oh, for heaven's sake! If only I'd been in that sea battle, I'd be a free man now. (p. 134) CHARON. I don’t take slaves. Not unless they fought in the sea-battle. (p. 140) CHORUS-LEADER. […] it does not seem right, When slaves who helped us in a single fight Now vote beside our allies from Plataea And put on masters’ clothes, like Xanthias here. Not that I disagree with that decision – No, no, it shows intelligence and vision (p. 160) The battle of Arginusae (406 BC) CHORUS-LEADER. Upstarts, nonentities, foreigners, and slaves – Rascals all! Honestly, what men we choose! […] Try the good ones again: if they succeed, You will have shown that you have sense indeed; And if things don't go well, if these good men All fail, and Athens comes to grief, why, then Discerning folk will murmur (let us hope): 'She hanged herself, but with a first-rate rope!' (p. 162) Slaves • Observational routine between the two slaves: SLAVE. There's nothing I like more than badmouthing my master behind his back. XANTHIAS. I bet you mutter a few things under your breath when he's had a go at you. SLAVE. Oh, yes! I like a spot of muttering. XANTHIAS. And what about prying into his affairs, eh? SLAVE. There's nothing quite like prying. (p. 163) Slaves • Formed a high proportion of Athens’ population; proportion in the audience itself unknown • Performed all sorts of jobs: domestic, manual, administrative, educational and sexual • Frequently drafted into military and naval service (some such rewarded with citizenship) XANTHIAS. Never a word about me. (p. 137) Comic inversion DIONYSUS. Well, if you're feeling so brave and heroic, how about taking my place? Here you are, you take the club and lion-skin - a chance to show your courage - and I'll carry the luggage for you (p. 153) DIONYSUS. You can hardly expect me to watch my own man Hard at it with dancing-girls on the divan, And giving me orders, likely as not (p. 155) Comic inversion DIONYSUS. You know, Xanthias, I've come to grow very fond of you. XANTHIAS. Oh no you don't! I know your game. I'm not playing Heracles again. DIONYSUS. Dearest Xanthias! Sweet Xanthias! (p. 156) XANTHIAS. I'll tell you what I'll do: I'll let you torture this slave of mine. (p. 157) Presentation of Gods • Athenian identity of gods and heroes: PLUTO. Goodbye, then, Aeschylus. Off you go with your sound advice – and save the city for us. (p. 190) • Location of the first scene • Heracles was frequently presented in comic and semi-comic modes (see Euripides’ Alcestis) • Aristophanes’ Dionysus is afraid of pain and death, and cowardly, foolish and petty (but comic convention allows this) • There is a visible disjunction between the cowardly, sex-driven figure onstage and the Iacchus worshipped by both the Frogs and the Chorus of Initiates (pp. 141-8). • Is he a more god-like figure by the end? • Remember the uncertain status of Dionysus in The Bacchae Comedy as festivity? • Etymology: Kômos • Material body as demystification: Dionysus as subject of scatological humour. • In carnivalesque imagery, according to Mikhail Bakhtin, the human body ‘is presented not in a private, egotistic form, severed from the other spheres of life, but as something universal, representing all the people’: • ‘The people’s laughter which characterized all the forms of grotesque realism from immemorial times was linked with the bodily lower stratum. Laughter degrades and materializes. […] To degrade also means to concern oneself with the lower stratum of the body, the life of the belly and the reproductive organs; it therefore relates to acts of defecation and copulation, conception, pregnancy, and birth. Degradation digs a bodily grave for a new birth; it has not only a destructive, negative aspect, but also a regenerating one.’ (1965: 1921) Comedy as festivity? • The play not only enacts but also depicts the ritual mockery of the real-life Mysteries: CHORUS. At distinguished bystanders / We’ll jest and we’ll jeer. (p. 149) • Aristophanes’ presentation of the cult of the Mysteries is presumably not dangerously impious, but a form of veneration through mockery… References • Bakhtin, M. (1965) Rabelais and His World, trans. H. Iswolsky, Bloomington: Indiana University Press. • Bergson, H. (1900) ‘Laughter’, in Sypher, W. (1956) Comedy, New York: Doubleday Anchor, 59-190. • Booker, C. (2004), The Seven Basic Plots: Why We Tell Stories, London: Continuum. • Freud, S. (1976) Jokes and their Relation to the Unconscious, trans. J. Strachey, ed. J. Strachey & A. Richards, London: Pelican, 132-161. • Griffith, M. (2013) Aristophanes’ Frogs, Oxford: O.U.P. • Palmer, D. J [ed.] (1984) Comedy: Developments in Criticism, London: Macmillan.