Medicine, Charity and the Poor Law

advertisement

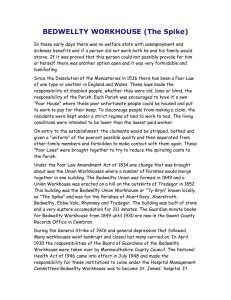

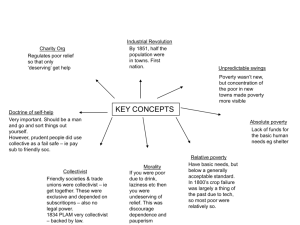

Medicine, Disease and Society in Britain, 1750 - 1950 Medicine, Charity and the Care of the Poor Lecture 4 Lecture Themes • Links between sickness and poverty • Access to medical care for the poor • Increasing population, urbanisation and industrialisation • Increasing pauperism • Was charity work always a good thing? Did it produce results? Was it effective? Lecture Outline • Poor Law Legislation – Comparison of medical provision under the Old and New Poor Law (1834) • Charitable Provision: Hospitals and Dispensaries • Who did they provide care for? • What care did charitable institutions provide? • How were Infirmaries organised and administered? • General voluntary, cottage and specialist hospitals The Old Poor Law 1601 The Elizabethan Poor Law Act 1662 The Act of Settlement Parishes or Townships unit of organisation • a compulsory poor rate • the creation of ‘Poor Law Overseers‘ to administer relief • parish/community to provide welfare relief Medical Provision • Medical men employed by contract, or paid per case, great variety of provision, including unqualified healers • Personal contact with poor important, idea of expensive but short-term solutions – flexible system • Out-relief key aspect of medical provision, workhouses usually less important Medical expenses at Birmingham workhouse, 1743-4. Expenses for medical relief of indoor paupers in the Mirfield (Yorkshire) Workhouse The Poor Law Reform Movement • Mid C18th – great population increase, harvest crises, epidemics, growth of towns and migration put a huge strain on the Poor Law system. • For ratepayers, the costs were held to be scandalous, while the poor felt the relief available to them was inadequate. • Pressure for reform resulted in the appointment of a Royal Commission in 1832. Commissioners were sent to 3,000 of the 15,000 parishes in every county in England and Wales. The Poor Law of 1834 1832-1834 The Poor Law Commission emphasised two principles: • Less eligibility: the position of the pauper must be ‘less eligible’ than that of the independent labourer. This meant that workhouse conditions should be more distasteful, unpleasant and uncomfortable, than any work or lifestyle available outside the workhouse. This principle existed to deter people from claiming poor relief. • The workhouse test: to obtain assistance, the poor person had to be desperate enough to enter the workhouse, to receive ‘in-door’ relief. No longer would paupers receive cash, food, goods or rent. The family would be split in the workhouse. 1834 Poor Law Amendment Act This established a national Commission for England and Wales. The Scottish Poor Law was not introduced till 1845. The New Poor Law • Poor Law Unions unit of organisation – large, contained several parishes, less personal contact. • Boards of Guardians were established in every union to supervise each workhouse, collect the poor rate and send reports to the central Poor Law Commission. • Poor Law medical Officers employed under contract. Work through Relieving Offices who judged on social rather than medical criteria. • Cost cutting was driving force. •Principle of ‘less eligibility’ and ‘workhouse test’ – Workhouse (indoor relief ) used rather than outdoor (medical treatment often only form of out-relief). •‘Deterrence’ replaced ‘entitlement’. Conditions varied but often dreadful. This vast new workhouse, opened on 4 August 1849, was for the united parishes for Fulham and Hammersmith. The largest workhouses not only segregated the poor according to age, sex, and health, but provided separate accommodation for each of the sexes according to ‘good’ and ‘bad’ character. Leeds Union Workhouse became part of St James’ Hospital and is now the Thackray Museum Engels, Condition of the Working Classes (1844) ‘Englishmen are shocked if anyone suggests that they neglect their duty towards the poor. Have they not subscribed to the erection of more institutions for the relief of poverty than are to be found anywhere else in the world? Yes, indeed - welfare institutions! The vampire middle classes first suck the wretched workers dry so that afterwards they can with consummate hypocrisy, throw a few miserable crumbs of charity at their feet’. 1860s pressure for reform • Medical profession, now much better organised and more powerful, campaigned for improvements. • 1866 Joseph Roberts, Medical Officer of the Strand Union Workhouse founded the Association for the Improvement of London Workhouse Infirmaries. • Public opinion also in favour of change. • Metropolitan Poor Law Amendment Act 1867 (later extended to provinces) began the process of moving infirmaries out of workhouses and medical need was to replace the ethos of less eligibility. Growth in Charitable Medical Institutions • Voluntary Hospitals: 1720 Westminster 1736 Winchester 1800 (34), 1861 (230) • Dispensaries: 1770 Aldersgate Street 1800 (33 of which16 in London) • Specialist Hospitals: 1804 Moorfields Eye 1860s there were 66 in London • Cottage Hospitals: 1859 Cranleigh 1875(148), 1895 (290) The architecture of many of the eighteenth-century British voluntary hospital reflected the wealth of its benefactors and was reminiscent of contemporary country houses of the landed gentry. Subscription • Patient admissions were strictly limited to the deserving poor who had subscribers’ recommendation. • Subscribers had the right to nominate or recommend patients for treatment. • The more they subscribed, the greater the number of patients they could nominate in any year. • Being able to cite high rates of recovery was an important aspect of gaining subscriptions. Who was eligible for care? • ‘Deserving poor’, ‘industrious or labouring poor’ ‘proper objects of charity’ • Not paupers but those who could not afford to pay for care themselves • Hoped that medical treatment would avoid pauperisation and encourage good and thrifty habits. Rules encouraged the reform of the poor Several categories of patients were excluded • Children under 7 • Pregnant women • Infectious diseases • Venereal diseases • Chronic diseases • Terminally ill • Insane Hospital Treatments • Sore legs, cough, scrofula (skin disease), lame hips, paralysis, fractured elbow, worms. • Accident cases also seen • Usually more men than women treated, with a focus on young working men Ward at the Middlesex Hospital, early 19th Century. Organisation • Subscribers - right to nominate patients • Governors - managed institution • Medical staff - honorary appointments • Matron and apothecary • Patients - free treatment This undated picture is labelled Luton cottage hospital. But Luton's mid to late 19th century cottage hospital was literally in a cottage - in High Town Road. Doncaster Dispensary, 1792-1867. These images show the small, simple premises that housed the institution in the mid-nineteenth century. Gateways to Death? • Florence Nightingale (1850s) - hospitals did harm • Thomas McKeown (late 1970s/1980s) - C19 hospitals positively did harm • John Woodward (1980s) - hospitals treated many patients successfully Why did hospitals develop? ‘Humanity, self interest, religion and the pursuit of social status made common cause to help those deemed unable to meet the cost of private medical care’. Keir Waddington The expansion in numbers of hospitals arose ‘not because of changes in medicine or perceived medical need, but because the economic and social climate changed in ways that made these institutions attractive to a range of political views’. Marguerite Dupree. Motivations • Altruistic • Economic • Upheld the social structure • Medical • Christian charity and civic virtue • Maintained the labouring classes, • Reduced poor relief • Reduced tensions between classes • Created middle-class identity • Contributed to the reform of the poor • Provided experience to doctors Roy Porter, ‘Gift relationship’ ‘An Act of conspicuous, self-congratulatory, stage-managed noblesse oblige underlay the infirmary. Poverty, malnutrition, premature ageing, occupational accidents and diseases would remain the abiding realities of life for the labouring classes, as would the coercive police functions of the poor law for ensuring a tractable labour force. The infirmary threw a cloak of charity over the bones of poverty and naked repression.’ Conclusion • Differences between Old and New Poor Law – were the poor any better off? • Why was the workhouse/hospital established? • Who did it benefit? • How successful was the hospital at treating patients?