Social Reform PowerPoint - N.Withey

advertisement

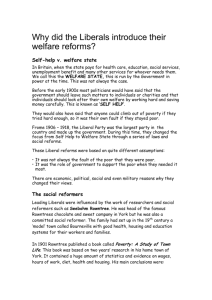

Unit 2: Topic 1: The needs of the people: Liberal welfare and social reforms, 1906-11 Introduction • This topic covers the major welfare and social reforms introduced by the Liberals in response to the needs of society at the start of the twentieth century. It looks at the main categories of people in need, at how their problems were publicised, and at why and how the Liberals responded. • Particular attention is given to the introduction of old age pensions in 1908, and to the sickness and unemployment insurance schemes introduced under the National Insurance Act of 1911. People in need • For many people, a consequence of Britain’s industrial growth during the nineteenth century had been prosperity. However, for a substantial minority it had been poverty, exploitation, squalor and disease. Governments had already accepted limited duties to help the needy, (eg. in a series of factory acts, notably in the period 183350). • During the late nineteenth century these governments had increasingly come to accept a responsibility to monitor conditions of work, to fight ill health, to give people a better and fuller life through improvements in such utilities and amenities as gas and electricity, and to give better educational opportunities. • In 1905, not long before they fell from power, the Conservatives had set up a Royal Commission to look into the final safety net for the needy - the Poor Law. Its report would come out in 1909. People in need Consequently, by the time the Liberals came to power in 1905, laissez-faire (non intervention) had already given way to collectivism (increased Government intervention) on a number of fronts. However, there was nothing remotely approaching the twentieth-century welfare state. Self-help, charity or poor law relief, either in the notorious workhouse or via outdoor relief (that is, relief in money or in kind, allowing recipients to live in their own homes), were often all that were available to the least fortunate in society. As the Liberals took office, industrial developments, the growth of towns and cities, and pressures from trades unionists and socialists were providing an extra urgency to find a solution to these well-publicised and deeprooted problems. Measuring the extent of Poverty • Serious attempts to measure the extent of poverty began in the 1880s. Case studies of poor families were produced in large numbers, revealing with increasing frankness to other sections of the population the way of life of the poor along with details of their standard of living. Two books revealed the extent of poverty. that generated discussion and debate. These publications were Life and Labour of the People in London, by Charles Booth (the first volume of which appeared in 1889 and the last in 1903), and Poverty, A Study of Town Life, by Seebohm Rowntree, which appeared in 1901. Rowntree defined living below the poverty line as lacking the means of buying the minimum of food, clothing and shelter needful of the maintenance of merely physical health. BOOTH • Booth’s book made an examination of London. He discovered that 30 per cent of the population of London fell below the poverty line. ROWNTREE • Rowntree, showed that Booth’s conclusions applied equally to provincial York, he suggested that more than 40 per cent of all the urban wage-earners in York, with their wives and children, were living below the poverty line. London was not a special case a poverty was a national problem in all cities. He wrote of families below the poverty line being unable to purchase a newspaper or postage stamps to send letters. They couldn’t save money or join a trade union because they couldn’t afford the subscriptions. Investigating Further • Investigators in other parts of the country, such as Reading, Northampton and Warrington, corroborated the findings of Booth and Rowntree. More research than ever before was being carried out on the pattern of economic equality in relation to such social indicators as birth rates and death rates, infant mortality, housing conditions and education. • Even as late as 1909, after the first legislation of the Liberal government had been enacted to tackle some of these problems of poverty, Charles Masterman, a Liberal MP and journalist, could still write that ‘poverty is the foundation of the present industrial order’ (The Condition of England, 1909). The message from these investigations was that one-third of Britain’s population was living on the edge of starvation. • More evidence was collected and published about what Rowntree had called the poverty cycle. This meant that there were phases in the lives of almost all workingclass families when income was insufficient to meet the basic cost of living. Therefore, national figures relating to primary poverty at any given moment would include only a fraction of those in primary poverty at some stage of their lives. Childhood, early middle age, when the number of family dependants was at its height, and old age were stages of privation for large numbers of people. Pressures from the Labour Party • • • • Publicity from social investigators such as Booth and Rowntree was reinforced by political pressure from an increasing number of workingclass Members of Parliament (MPs). Pressures from new working-class and socialist political groups and parties’ In 1900, the establishment of the Labour Representation Committee (LRC), effectively the birth of the Labour Party, brought together trades unionists and the new working-class parties to fight Parliamentary elections in future with commonly agreed candidates. The 29 LRC candidates elected in 1906 formed themselves into the Parliamentary Labour Party (PLP). There is an argument that the Liberal social reforms were introduced to entice voters away from the infant Labour Party. In 1906, David Lloyd George had spoken of Labour as ‘a force that will sweep away Liberalism’ unless the Liberals moved more decisively to social reforms. By-election results went badly for the Liberals in 1907&1908, leading Lloyd George to argue that: ‘It is time we did something that appealed straight to the people to stop the electoral rot.’ As his was arguably the key role in pushing his party into constructive social welfare reforms between 1908 and 1911 on a scale hitherto unmatched, it is important to give some serious consideration to this argument. Pressures from the Labour Party cont.. • • While wooing voters from Labour is a consideration you must keep in mind when looking for reasons to explain the Liberal social reform programme, it would be quite wrong to dismiss it as originating solely in political expediency to keep Labour at bay rather than being based on the principle or conviction that reform was necessary. • It is worth pointing out that social reform played little part in the campaigns of most Liberal candidates in the general election of January 1906 suggesting that, at that time, the challenge of Labour was not considered particularly significant. The main election issue had been the argument about whether the country should abandon its long-standing commitment to free trade or, as the Conservative Party was advocating in its proposals for tariff reform, move towards the introduction of protectionist measures, with special concessions for food producers in the British Empire. Liberal welfare and social reforms – how radical was reform? • The ministries of Henry CampbellBannerman (from 1905 to 1908) and Herbert Asquith (from 1908) led Britain into one of the great eras of reform in modern times. Arguably, the steps both men took to combat or alleviate poverty and social need in that time were so radical that we can credit them with laying the foundations of the twentieth-century welfare state. Liberal welfare and social reforms – who led reform? • The reform programme owed much to the more radical members of the government, notably Asquith, Lloyd George and Winston Churchill. The pace of reform quickened after Asquith became prime minister in 1908 and it was largely in the three years from 1908 to 1911 that the foundations of a welfare state were laid. • Direct taxation was increased to pay for the various measures introduced. Most famously, in 1909 Lloyd George, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, announced to Parliament that he had framed a ?War Budget? to raise money ‘to wage implacable warfare against poverty and squalidness’. Reforms can be categorised under the headings of provision of care and protection for: • • • • • children the old the unemployed and low waged workers suffering through ill health and injury at work. Lloyd George, Chancellor in 1909 Reforms for Children • The Free School Meals Act was passed in 1906 to allow local authorities to provide school meals for children in need. It had not been planned by the new government and was enacted in response to an original private member’s bill introduced by a Labour MP. Although the legislation was voluntary, by 1914, 158,000 children annually were being provided with free school meals. Parents of children being helped were not branded as paupers and, for example, fathers did not lose their rights to vote (assuming they had a vote), which is what would have happened if they been obtaining poor law relief. There was keen social debate about the Education Act, particularly about the principle that the state rather than parents should feed needy children. The Free medical inspections Act was passed in 1907. Again, this hadn,t been planned and owed more to civil servants building on the public health legislation of the Victorian age. It was also voluntary although few local authorities failed to provide medical inspections by 1914. • |The Children’s Act of 1908 was aimed to give young people better legal protection for example, by establishing separate juvenile courts. The Old • Joseph Chamberlain, among others, had been pressing for some form of old age pension for a number of years. In his book entitled The Aged Poor: A Proposal (1907), Charles Booth set out some of the basic facts about poverty among old people who, after years of hard work, had no possibility of financial relief. The Old Age Pensions Act of 1908 was, therefore, the climax of sustained agitation. There was considerable debate about the proposals for old age pensions from the time they were announced in the government’s budget of 1908. Some 1.2 million was set aside for the scheme, which was non-contributory ( in other words, recipients would not be expected to make any contributions during their working lives). Under the act, a pension was to be provided for everyone over the age of 70 whose income did not exceed £31.50 a year provided they were not already in receipt of poor law relief. The pension was issued on a sliding scale, with a maximum of five shillings (25p) for an individual payable if that person’s annual income was less than £21. The maximum amount payable to a married couple was seven shillings and sixpence (37.5p). There were a number of moral qualifications, too; the pensioner had to have been regularly employed and not been in prison during the previous ten years. This was hardly an overly generous measure, hedged with restrictions and qualifications Joseph Chamberlain The Unemployed and the Low Waged Many new facts were being collected about unemployment and its incidence. In 1908 William Beveridge, who was later to play such an important part in the making of the twentieth-century welfare state, published his work Unemployment, A Problem of Industry. This exposed the social plight of the casual labourer and showed how the trade cycle, governed by shortage and surplus, supply and demand, affected the security of large numbers of workers in particular industries. Beveridge argued that unemployment was an inevitable by-product of trade depressions in a capitalist industrial system and should therefore be treated more sympathetically. The state, he argued, had a responsibility to: • help the unemployed to find work • support the unemployed while out of work • set up job creation schemes. The Unemployed and the Low Waged cont… • Between 1909 and 1911, and against a background of about 800,000 unemployed (7.2 per cent of the total workforce), the Liberals responded to Beveridge’s arguments by introducing a number of measures to help the unemployed. • In 1909 labour exchanges, the forerunners of Job Centres, were set up to help the unemployed find work. Beveridge was now a civil servant at the Board of Trade, and he and his minister, Winston Churchill, were responsible for launching this new venture. The exchanges had a marked, if limited, success. In the year leading up to the First World War, some two million people registered and it has been estimated that, overall, about 25 per cent of those people were offered jobs. In 1911, an unemployment insurance scheme was introduced. This was undertaken under the second part (Unemployment) of the two-part National Insurance Act (part one related to health). • The rationale behind this innovation was based, in part, on surveys into the problem of unemployment in trades particularly susceptible to casual unemployment or seasonal unemployment - for example, building and shipbuilding. The Unemployed and the Low Waged cont… • Unlike old age pensions, unemployment insurance was a contributory scheme. Each insured worker paid a compulsory contribution of 2 1/2 d (1p) a week. Employers paid the same and the state contributed another 1.7d (0.5p) to the insurance fund. Benefits paid out from the fund could reach as much as seven shillings (35p) a week, payable for a maximum of 15 weeks in a year, provided claimants could prove they had been in insured work for at least six months in the previous five years. The scheme was compulsory only for workers in the trades identified and, initially, about 2.25 million workers were covered. However, many of these were skilled workers, which means they couldn’t really claim to be in the category of the truly needy. In the last year before the First World War, some 23 per cent of those covered made a claim. Workers suffering through ill health and injury at work cont.. • Concerns about the health of the nation had been growing, as you have seen. About 6-7 million people probably already had some form of insurance against illness, often through friendly societies and private insurance schemes. However, this did not include many really poor people and the decision was taken to introduce a compulsory insurance scheme against illness for virtually all low-paid workers. Part one of the 1911 National Insurance Act (Health) provided this. As with unemployment insurance, this was a contributory scheme, with workers paying 4d (1.5p) a week, employers 3d (1p) and the state, through taxation, 2d (1p), thus giving rise to Lloyd George’s slogan of ‘9d for 4d’. This was much more comprehensive than unemployment insurance in its coverage. All workers between the ages of 16 and 70 who were earning up to £160 a year were compulsorily included. By 1913, these workers numbered over 13 million. • The benefit for a sick worker was 10 shillings (50p) a week for a man and 7s 6d (37.5p) for a woman. In addition, the insured worker was entitled to free treatment from a doctor and to approved medicines. Women were entitled to 30 shillings (&1.50) maternity benefit. Lloyd George was the minister with most responsibility for the scheme, which was modelled on the German system introduced in the 1880s by the German Chancellor, Otto von Bismarck. Workers suffering through ill health and injury at work cont.. • However, the scheme in Britain had considerable opposition, which came from a broad cross-section of people and organisations. Doctors were reluctant to become effectively state employees. Friendly societies and insurance companies resented competition that might put them out of business. Employers saw their contributions as a burden. Workers themselves, particularly those on the lowest pay, were unhappy at having to pay weekly contributions, whatever the insured benefit. Opposition from doctors and friendly societies was eventually overcome, with the latter sharing administration of the scheme with insurance companies and trades unions. Workers suffering through ill health and injury at work cont.. • The National Insurance Act, particularly the health insurance element, was arguably the most important social reform of the period, equivalent to the Parliament Act (to be looked at in detail in the next topic) in the Constitutional sphere. It was a radical reform in its own right and also pointed the way to future legislation. Achievements of the social reforms • It is possible to summarise the social reforms introduced by the Liberal ministries in this period as follows.1906 Trades Disputes Act; school medical services set up.1907 School Medical Service was set up.1908 Childrens Act; eight-hour day for miners; Old Age Pensions Act. 1909 Labour Exchanges set up; Trade Boards Act. 1911 National Insurance Act. Although this is an impressive list, it would be wrong to assume that potential beneficiaries were universally satisfied with the Liberal administrations. In fact, they were attacked from all sides, and the years 1910 to 1914 were disturbed and even violent. Conclusion: foundations of a welfare state? • Measures to improve the diets and health of children, the introduction of old age pensions, the establishment of labour exchanges and the establishment of trade boards to fix wage rates in ‘sweated industries’ were, without doubt, innovative. Possibly most important, both in its radical innovation and implications for future developments, was the National Insurance Act, introducing health insurance and limited unemployment insurance, thus starting a process central to the twentiethcentury welfare state. I would argue that you are quite in order in describing these Liberal social reforms as representing the origins of a welfare state. Of course, there were considerable shortcomings when measured against, for example, the Beveridge NHS blueprint of 1942 . Radical attention to provision of better housing and education, for example, are two glaring omissions from the pre-war legislation. • One final consideration should be made here: the Liberal Party’s reform programme arguably ran out of steam after 1911. This could be attributed, in part, to the problems it faced in the immediate pre-war years, which included the Constitutional Crisis with the House of Lords and the Problem of Home Rule for Ulster. t i o n o f l Now that you have finished this topic you should feel confident that a what have been termed ‘the you understand the main features of b needs of the people’ early in the twentieth century. You should be o able to describe how these needs were publicised by such people as Seebohm Rowntree and Charlesu Booth. You will be able to explain how this increasing publicityr and other factors, such as pressure from the ballot box and from e the infant Labour Party, helped to push the Liberals into a xcomprehensive programme of social reform between 1906 and 1911.The topic looked at c important reforms such as the introduction of old age pensions, the h innovation of labour exchanges, measures to improve the health and a fitness of children, and the introduction of insurance against ill health n and, in a more limited way, unemployment. You will be aware of the main detail of these measures, andg of their impact and shortcomings. You will now be familiar with the concept of a e welfare state as defined later in thes twentieth century and should be able to measure the achievements, of the Liberals against this concept. m e a Summery • Further reading • Constantine, S, Lloyd George, Routledge Lancaster Pamphlets, 1992 • Evans, E J, The Birth of Modern Britain, 1780?1914 (Chapters 30 and 31), Addison Wesley Longman Advanced History series, 1997 • Hay, J R, The Origins of the Liberal Welfare Reforms, 1906?14, Macmillan Studies in Economic and Social History, 1975 • O?Day, A (ed.), The Edwardian Age: Conflict and Stability, 1900?14, London, Macmillan Problems in Focus, 1979 • Pugh, M, Lloyd George, Longman Profiles in Power, 1988 • Watts, D, Whigs, Liberals and Radicals, 1815?1914 (Chapter 6), Hodder & Stoughton Access to History series, 1995