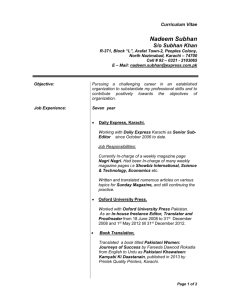

The Express Tribune13, May 11 th , 2012.

advertisement