I. What is Population Policy?

advertisement

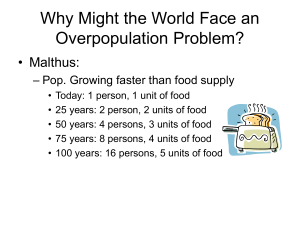

Population Policy: Whose Population? What Policy? Dr. SHAE Wan-chaw APSS, HKPolyU 25 April 2009 I. II. III. IV. V. What is Population Policy? World Trends Why Need a Pop Policy? Critique of Pop Policy Sense & Nonsense in Pop Policy VI. A People-based Pop Policy? I. • 1. 2. 3. 4. What is Population Policy? No accepted definition (UN 1973:632). It can be: Explicit (stated intention), implicit (unstated aim) or unintended. Direct (encouraging birth control) or indirect (compulsory education). Punitive/coercive or facilitative/voluntary. Domestic or international (giving/not giving aid to other countries). • Narrow definition: ‘all deliberate govt actions (such as laws, regulations, & administrative programs) intended to influence pop growth, size, distribution, & composition.’ (Lucas 2003:1) • A broad definition may include unintended influences: ‘governmental actions that are designed to alter pop events or that actually do alter them’ (Berelson 1971:173). But this is debatable. • May also include population-responsive policies (the ways that govts respond to pop changes). • A pop policy normally includes: 1. Size: a numerical goal &/or growth rate. 2. Composition & distribution of various demographic variables: age, sex, race, education level, location etc. 3. Relationship of (1) & (2) to economic, social, political & other collective goals. 4. Assessment & deployment of various policies/means to the achievement of (1), (2) & (3), eg: natural increase policy, immigration policy, education policy, employment policy etc. II. World Trends • In 1927 world pop = 2 billion. 1974 ↑ to 4 b; & in 2000 it ↑ to 6 b (2009 at 6.8 b). The UN projected that it will reach 9.1 b by 2050. The projected ↑(2.3 b) will come from developing countries, which pop is expected to↑ from 5.6 b in 2009 to 7.9 b in 2050. • India – the 1st 3rd world country to endorse an active pop policy in 1952. • By 2001, 92% of all countries supported family planning programs & contraceptives, either directly (75%) or indirectly (17%), through NGOs. Govt. Views on Level of Fertility (UN 2003:2): No. of Countries (%) Year Too low Satisfactory Too high Total 55 (37) 85 (44) 150 (100) 193 (100) World 1976 2001 16 (11) 34 (18) 79 (53) 74 (38) More developed countries 1976 2001 7 (21) 24 (50) 27 (79) 23 (48) 0 (0) 1 (2) 34 (100) 48 (100) Less developed countries 1976 2001 9 (8) 10 (7) 52 (45) 51 (35) 55 (47) 84 (58) 116 (100) 145 (100) Least developed countries 1976 2001 3 (7) 0 (0) 26 (62) 11 (22) 13 (31) 38 (78) 42 (100) 49 (100) Govt. Policies on Level of Fertility (UN 2003:4): No. of Countries (%) Year Raise Maintain Lower No intervention Total World 1976 2001 13 (9) 26 (13) 19 (13) 19 (10) 40 (27) 86 (45) 78 (52) 62 (32) 150 (100) 193 (100) More developed countries 1976 2001 7 (12) 15 (31) 7 (21) 4 (10) 0 (0) 1 (2) 20 (59) 28 (56) 34 (100) 48 (100) Less developed countries 1976 2001 6 (5) 11 (8) 12 (10) 14 (10) 40 (34) 85 (59) 58 (50) 35 (24) 116 (100) 145 (100) Least developed countries 1976 2001 1 (2) 0 (0) 2 (5) 4 (8) 6 (14) 34 (69) 33 (79) 11 (22) 42 (100) 49 (100) • Many developing countries have an explicit pop policy; whereas most developed ones don’t. • World pop growth ↓ since 1980s. The % of countries that viewed fertility as too high leveled off after 1996 at about 45%. • Countries that view fertility as too high are more likely to intervene than those that view fertility as too low. • In general, policies that attempted to ↑ fertility tend to be even more ineffective than those that attempt to ↓ fertility. III. Why Need a Pop Policy? • To ↑ human welfare: ‘pop & development are interrelated: pop variables influence development & are also influenced by them’ (World Pop Conference 1975:157, para 14c). • It is commonly believed that: – There is a pop problem, esp. in the 3rd world. – Pop ↑ economic ↓ poverty, hunger, environmental devastation political unrest threatening the West. • According to UN, an ‘aging pop’ = one with 10% of its pop that is 60+ yrs old. In 1999, there were 580 m people aged 60+ globally. By 2009, it has reached 739 m (or1/9 of the world’s population). It is projected that it will be tripled to 2 b by 2050. Even the ‘aged pop’ is itself aging: in 2006, 13% of them (94 m) are 80+, & it is estimated that it would reach 20% (394m) by 2050. • It is widely believed that pop aging greater demand for care & ↑ health costs. IV. Critique of Pop Policy • There is a tendency to regard pop policy, as based on demography, is or should be ‘scientific’. • Pop experts often evoke the image of an apocalypse brought on by adverse pop trends. Salvation justifies any draconian programs requiring sacrifice & submission. • But pop policies have often been based on myths & ideologies than on science & evidence. • But the study of human pop ≠ a natural science. The rate of pop growth & resources depletion cannot be predicted with accuracy over any extended periods of time. Egs: - Malthus (1789) was wrong. Food production can ↑ faster than pop. World pop is at least 6x what it was in 1800, yet there is still more than enough food to support them. From 1961-1994 global production of food doubled. - J. Simon & P. Ehrlich’s famous 10 yr bet in 1980 on the price of raw materials. • Even the term ‘overpopulation’ cannot be defined unambiguously: - Rate of natural increase – US between 1790 & 1800 = 3%/yr, whereas that of the 49 least developed countries in 2009 is 2.3%/yr. - Birthrate – US in the 1790s was 55 per 1000, higher than 127 national birthrate estimates of the World Bank (1993). - Pop density – France > Indonesia, Japan > India, & Singapore > Bangladesh. Monaco = the most overpopulated state. • Dependence ratio – in 1980 Israel > Sri Lanka; & in 1990 the least overpopulated societies in the world were HK & Singapore. • Biologists use the term ‘carrying capacity’ to denote the maximum no. of organisms a given environment can support. This notion cannot easily be applied to humans as our capacity to alter our ways of life means that it is impossible to predict when our ability to provide for additional people will end, if ever. • Nor is the notion of an ‘optimum pop’ value& problem-free: - The notion ≠ an end in itself. It should not be isolated from other social priorities. Most discussions focus on a narrow economic criteria of value to the neglect of other values. But economic development ≠ the good life. - It assumes that the attainment of individual & social goals are unambiguously affected by the size & characteristics of the pop. But the relation between pop & particular social conditions are not easy to ascertain. • The pop experts tend to blame the victims, ie, that those who suffer from poverty are the ones who have caused the problem. • Historically, pop ↑ correlates with economic prosperity, pop ↓ with stagnation. The last 2 centuries has witnessed a tremendous growth both in world pop & economic growth. • In 1971 Bangladesh won independence from Pakistan. Both had around 66 m people growing at 3% a yr. Both were poor, rural & Muslim. Bangladesh started emphasising family planning in 1976. 30 yrs later, it had a pop of 120 m whereas Pakistan had 140 m. But Pakistan’s GDP was 2x that of Bangladesh. • Greater pop may ↑ demand for goods & services stimulate technological & agricultural innovation ↑efficiency & supply. • But in a capitalist economy, food production is not determined by need, but by demand. • The true cause of world hunger ≠ overpop, insufficient food, or famine, but poverty & inequality. • To assume that poverty can be eliminated by preventing the birth of poor people is to commit an elementary fallacy. • All attempts to control or reduce pop often mask racists, sexist or classist policies aimed at controlling ‘the other’. The fear of a ‘pop bomb’ has more to do with which babies are being born than how many are being born. • The prevention of 1 American birth = birth of 50 Indians in terms of energy use (US has only 5% of world pop, but emitted 30% CO2); yet the US worry about the growth of the Indian pop (Hofsen 1980) . • Any pop policy inevitably touches upon the touchy questions of : - The rights of the living vs the unborn. - Individual freedom vs collective good. - Duties to society & society’s responsibilities. - Drawing the line between ‘us’ & ‘them’. - Tensions between the sanctity of the family, destiny of one’s nation/race, & God’s will. - Value of life & prospects of mankind. ‘As for “pop policy”, the sanest response is not to have one. The only humane approach is to let each family, in every country, choose its own fertility rate according to its own desires & concerns for the future…. The alternative is tyranny & torment.’ (Lawson 2008) V. Sense & Nonsense in Pop Policy • There is no question that uncontrolled pop growth environmental crises. But does the West really want to ↓ fertility rate? Breastfeeding is the most effective & natural birth control devise. However, breast-feeding is disappearing in the West because of concerns about body image. It has also markedly ↓ in the periphery because of advertising & the sales of powdered infant formula. • By 1980s, many countries’ budget for family planning > all other health-related services combined. Is this sensible? - In 1980, govt expenditure per contraceptive user was US$68 in Ghana & $69 in Nepal; whereas total govt expenditure on all health programs were $20 per family in Ghana & $8 in Nepal (Eberstadt 1994). • There’s also no evidence to suggest that family planning programs have a direct causal impact on fertility rate: - In most countries, fertility ↓ was well underway before the launching of any family planning program (India being the exception). - In 1989, 63% of Turkey’s married women of reproductive age used contraception, with a fertility rate of 3.4 births/women. Japan’s figures were 56% & 1.5 births/women. • But if there is much debate surrounding the notion of an optimum pop size, there is less disputes as to the characteristics of an optimum pop, esp. over the long term: - A low level of mortality. - A stable age & sex distribution. - A near 0 growth rate. - A ↓ rate of consumption & pollution. • The problem lies in balancing these objectives with other imperatives. • More & more countries are facing with a set of contradictory imperatives: - Fiscal pressures to ↑ the no./% of working pop either by ↑ fertility or immigration. - Economic need for low-skilled labor &/or high-skilled workers. - Social need of treating (potential) immigrants fairly & of integrating them. - Political risk of a rising xenophobia & antiimmigrant populism. VII. A People-based Pop Policy? • Central to a people-based pop policy is to put people’s needs at the centre, to respect their rights, to ↑ their freedom & security so that they can make choices rationally. • It must also contain: 1. A public philosophy of citizenship – what rights & benefits do we wish to confer on them, & why? 2. An articulation of relationship between pop size, composition & growth rate to other social & collective goals. 3. A comprehensive & coherent system of social policies that correspond to the above principles based on a comparative analysis of the pros & cons of different policy options. 4. A justification of whom should we admit & whom should be counted as citizens, & why some are rejected: ‘Quality migrants’ & capital investment entrants vs the principle of family reunion (mainlanders born of HK parents); foreign domestic ‘helpers’ vs expatriate workers etc. • HK did not have an pop policy until 2003. ‘香港人口政策的主要目的,……是為了致力提 高香港人口的總體素質,以達到發展香港成為 知識型經濟體系和世界級城市的目標。為此, 我們要有效處理人口老化問題, 建立積極、 健康老年的新觀念, 推動新來港人士融入社 會, 更重要的是, 確保我們的經濟能夠長遠 持續發展。我們認為, 達到這些目的, 就可 以穩步改善香港市民的生活水平。’ (人口政 策專責小組報告書,2003:vii) • As such, it ≠ a document on pop policy but an economic policy, & a narrow one at that. • - - In the ‘newspeak’ of the HK govt, the Report twisted the term ‘sustainability’ to suit its ends: Economic sustainability = ways to ↑ our workforce’s productivity & enhance economic vibrancy. Fiscal sustainability = minimizing govt commitment & responsibility. Social sustainability & integration = limit new arrivals’ eligibility to public services (the so-called ‘7-yr’ residence requirement). • Economic development certainly has a role to play; but it needs to be ‘de-centred’ so that people are not treated as means for ‘the economy’, but vice versa.