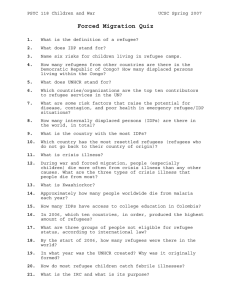

Yvonne's project- finall - Institute Of Diplomacy and

advertisement