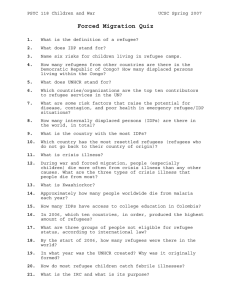

School of Global Affairs and Public Policy

advertisement