Energy and Weight Gain

advertisement

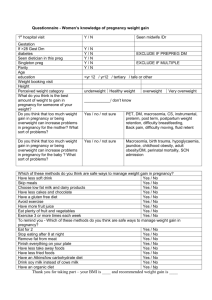

Energy and Weight Gain in Pregnancy 2012 Energy Requirements in Pregnancy • Increased energy costs in pregnancy: – increased maternal metabolic rate – fetal tissues – increase in maternal tissues DRI for Energy in Pregnancy 2002 Estimated Energy Requirement • Average dietary energy intake that is predicted to maintain energy balance in a healthy adult of a defined age, gender, weight, height, level of physical activity consistent with good health. • In children, pregnant and lactating women the EER is taken to include the needs associated with deposition of tissues or secretion of milk BEE: Basal Energy Expenditure • BEE = energy consumed while at rest and fasting • In pregnancy BEE increases due to metabolic contribution of uterus and fetus and increased work of heart and lungs. • Variable for individuals Growth of Maternal and Fetal Tissues • Calculations Based on: – Hytten – IOM weight gain recommendations T1 and T2 ~ 180 kcal per day Longitudinal Data from DLW Database • Median TEE (total energy expenditure) change from non-pregnant was 8 kcal/gestational week. • TEE changes little in first trimester. Variations in Energy Requirements • Body size - especially lbm • Activity: – most women decrease activity in last months of pregnancy if they can – increased energy cost of moving heavier body • BMR – rises in well nourished women (27%) – rises less or not at all in women who are not well nourished • -Diet Induced Thermogenesis? Evidence of energy sparing in Gambian women during pregnancy: a longitudinal study using whole-body calorimetry (AJCN, 1993) • N=58, initially recruited, ages 18-40 – 25 became pregnant – 21 participated in study protocols – 9 completed BMR and 24 hour energy expenditure – 12 completed BMR • Adjusted for seasonality, weight loss expected during wet season Poppitt et al., cont. • Mean maternal prepregnancy weight was 52 kg • Mean prepregnancy BMI was 21.2 + 2 • Mean birthweight was 3.0 + 0.1 • Mean gestational length was 39.4 • Mean weight gain was 6.8 kg • Mean fat gain was 2.0 kg at 36 weeks Poppitt et al., cont. • BMR fell in early pregnancy • Values per kg lbm remained below baseline for duration of pregnancy • Individual variation was high Poppitt et al., cont. • Energy sparing mechanisms may act via a suppression of metabolism in women on habitually low intakes. • This maintains positive balance in the mother and protects the fetus from growth retardation Prentice and Goldberg. Energy Adaptations in human pregnancy: limits and long-term consequences. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;71(supple):1226S-32S. Longitudinal assessment of energy balance in well-nourished, pregnant women (Koop-Hoolihan et al, AJCN, 1999) • N=16, SF area – 10 became pregnant • BMI range was 19-26 • Mean weight gain at 36 weeks was 11.6 + 4 kg • Mean birth weight was 3.6 kg Koop-Hoolihan, cont • Protocol: 5 times before pregnancy, 3 times during, once 4-6 weeks postpartum – RMR (resting metabolic rate/metabolic cart) – DIT (diet induced thermogenesis/metabolic cart) – TEE (total energy expenditure/doubly labeled water) – AEE (activity energy expenditure/difference between TEE and RMR) – EI (energy intake/3 day food records) – Body composition - densitometry, tbw, bmc with absorptiometry Koop-Hoolihan, cont • Women with the largest cumulative increase in RMR deposited the least fat mass (this was the only prepregnant factor that predicted fat mass gain) • In all indices there was large individual variation • Average total energy cost of pregnancy was similar to work of Hytten and Leitch (1971) • Food intake records indicated 9% increase in kcals with pregnancy, but highly variable Weight Gain in Pregnancy • Components & patterns • IOM recommendations – 1990 – 2009 Components of Weight Gain Patterns of Maternal Fat Accretion Maternal Weight Gain Number Included Year in Analysis < Ideal > Ideal % % 2009 917,032 21.2 48.2 2007 920,893 21.4 48.6 2005 661,128 22.2 48.9 2003 594,311 21.7 49.6 2001 555,537 22.4 48.6 1999 505,065 24.8 46.5 1997 410,959 30.9 40.8 1995 363,959 27.6 42.6 1993 209,074 28.6 40.3 1991 110,404 29.3 41.0 1990 118,301 30.6 40.6 1989 104,119 32.1 36.9 1988 17,681 33.0 37.4 National Pregnancy Nutrition Surveillance http://www.cdc.gov/pe dnss/pnss_tables/htm l/pnss_national_table 16.htm Percent of Women Gaining <7.3 kg 37-39 weeks 40 weeks Non-Hispanic Black 15.5 14.0 Hispanic 12.4 11.2 Non-Hispanic White 8.8 8.0 All US 10.4 9.3 Hicky, CA. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;71(supple):1364S-70S. Characteristics of Women Associated with Inadequate Weight Gain • • • • • • • Lower education levels Unmarried Aged > 30 years Smoking Multiple parity Unintended pregnancy Psychosocial characteristics such as attitude toward weight gain, social support, depression, stress, anxiety, and self-efficacy. Hicky, CA. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;71(supple):1364S-70S. 1990 IOM Recommendations Institute of Medicine. Nutrition during pregnancy, weight gain and nutrient supplements. Report of the Subcommittee on Nutritional Status and Weight Gain during Pregnancy, Subcommittee on Dietary Intake and Nutrient Supplements during Pregnancy, Committee on Nutritional Status during Pregnancy and Lactation, Food and Nutrition Board. Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 1990 Cogswell M, Serdula M, Hungerford D, Yip R. Gestational weight gain among average-weight and overweight women—what is excessive? Am J Obstet Gynecol 1995;172:705–12 1990: Recommended total weight gain in pregnant women by prepregnancy BMI (in kg/m2) Weight-for-height category Recommended total gain (kg) Low (BMI <19.8) 12.5–18 Normal (BMI 19.8–26.0) 11.5–16 High (BMI >26.0–29.0)2 7–11.5 Adolescents and black women should strive for gains at the upper end of the recommended range. Short women (<157 cm) should strive for gains at the lower end of the range. The recommended target weight gain for obese women (BMI >29.0) is 6.0. Incidence of adverse outcomes for 6690 pregnancies in San Francisco Parker J, Abrams B. Prenatal weight gain advice: an examination of the recent prenatal weight gain recommendations of the Institute of Medicine. Obstet Gynecol 1992;79:664–9 Percentage of US women with normal prepregnancy weights who retained >9 kg 10–24 mo postpartum relative to prepregnancy weight (Parker J, Abrams B. Differences in postpartum weight retention between black and white mothers. Obstet Gynecol 1993;81:768–74) Percentage of US Women Who Gained >40 pounds during pregnancy (MMWR, February 2008) (source = birth certificates; singleton delivery only) Prepregnancy Obesity* Washington State,1992-2005 12 11.4 10 Percent 8 6 5.3 4 1.3 2 0.3 0 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 Obesity *Obesity 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 Morbid Obesity is defined as prepregnancy weight > 200 lbs Morbid obesity is defined as prepregnancy weight > 275 lbs Obesity by Parity and Race/Ethnicity Percent Obese (BMI> 30) Washington State, 2003-2005 45 40 35 30 25 20 15 10 5 0 39 35 29 28 24 24 19 16 13 9 Hispanic White African American Primiparous American Indian Multiparous Asian/PI Weight Gain During Pregnancy: Reexamining the Guidelines (IOM, 2009) • • • • • • • • New Guidelines Conceptual Framework Composition and Components of Weight Gain Determinants of Weight Gain Maternal Consequences of Weight Gain Child Consequences of Weight Gain Determining Optimal Weight Gain Achieving Recommendations 2009 Guidelines for Specific Populations Women of Short Stature “unable to identify evidence sufficient to continue to support a modification of GWG guidelines” Pregnant Adolescents “unable to identify evidence sufficient to continue to support a modification of GWG guidelines” Racial or Ethnic Groups “Recommendations should be generally applicable to the various racial or ethnic subgroups” Women with Multiple Fetuses Provisional Guidelines for Twins (at term): Obesity Classes II and III Insufficient evidence to develop more specific recommendations. –Underweight: insufficient evidence –Normal Weight: 17-25 kg –Overweight : 14-23 kg –Obese: 11-19 kg Determinants of Gestational Weight Gain Determinants: Social & Policy Findings Health Services Evidence for influence is weak; advice missing, inconsistent, erroneous Community “neighborhood environments can influence GWG by providing access to healthy foods and opportunities for PA” Family Married women more likely to gain within guidelines; association between partner violence and insufficient GWG; family support associated with good GWG SES Interactive and confounding effects; food insecurity in obese women associated with high GWG Determinants: Genetics • Maternal: insufficient evidence • Fetal: GWG associated with birthweight; preliminary conclusions about fetal genotype and birthweight: (a) there is a fetal genotype effect on weight at birth (about 30 percent of the adjusted variance) (b) both parents’ genes influence birth weight with a stronger effect for maternal genes (c) specific allelic variants have been associated with weight at birth (d) mutations in GCK and HNF1β are associated with low birth weight (e) mutations in HNF4α are associated with high birth weight (f) a few quantitative trait loci on chromosomes 6, 10, and 11 have been uncovered from genome-wide linkage scans Determinants: Maternal Factors Pregravid BMI Depression In general GWG decreases as BMI increases; but large variation Mild n/v no adverse effect; HG lower GWG AN: variable BN: greater GWG Both low and high GWG Stress Low GWG Hyperemesis Gravidarum Disordered Eating Determinants: Maternal Behaviors Diet Relationship between energy intake and GWG; insufficient evidence for diet composition and GWG Physical Inverse relationship between PA and Activity GWG Tobacco “Limited” evidence for inverse association with GWG; smoking has independent effect on birth weight. “There remains a lack of information to relate dietary intake or physical activity to GWG even though they are primary determinants of weigh gain in nonpregnant individuals.” Consequences of GWG for Mother • Strong association between high GWG &: – increased risk of cesarean delivery – postpartum weight retention (3 mos to 3 yr) • Modest association: – failure to initiate breastfeeding • Inconclusive evidence: – pregnancy complications like glucose intolerance and gestational hypertensive disorders – long term health consequences Consequences of GWG for Child • Studies consistently show linear relationship between GWG and birthweight for gestational age. • Some, but limited evidence for associations between GWG and: – – – – – Still birth Preterm birth (at both low and high GWG) Childhood asthma and low GWG High GWG and some cancers and ADHD High GWG and childhood obesity Recent Studies on Impact of GWG on Offspring Obesity Zilko et al. Am J Obset Gynecol, 2010 In NLSY: GWG associated with child overweight Mamun et al. Circulation, 2009 In Australian cohort : Greater GWG associated with greater offspring BMI in early adulthood Von Kries et al. Int J Pediatr Obes, 2010 Large German cross-sectional study: higher than average GWG accounts for moderate increase in offspring overweight at ages 3-17 Beyerlein et al. PLoS One. 2012; 7(3): e33205 Combined data from 3 large German cohorts: In adjusted models, positive associations of total and excessive GWG with mean BMI SDS and overweight were observed only in children of non- overweight mothers Determining Optimal Weight Gain • “Evidence is remarkably clear that prepregnant BMI is an independent predictor of many adverse outcomes of pregnancy.” • Limited data to link GWG to health outcomes of mothers and children after the neonatal period. Approaches to Achieving Recommendations Comparison of Recommended Weight Gain & Actual Outcomes IOM States that full implementation of guidelines would mean: • Preconceptual services offered to all overweight & obese women to help them reach a healthy weight before conceiving • Offering services, such as counseling on diet and PA during pregnancy to all pregnant women. • Offering services to all postpartum women 5 Action Recommendations 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. DHHS conduct routine surveillance of GWG and postpartum weight retention All states adopt revised version of birth certificate that includes maternal pp weight, height, weight at delivery, gestational age at last measured weight (and strive for 100% completion of fields). Fed/state/local agencies and health care providers inform women of importance of conceiving at a normal BMI Agencies/organizations adopt new guidelines and publicize to members and women Providers of prenatal care should offer counseling on dietary intake and PA that is tailored to life circumstances.