engaging-buddhism-full-021114

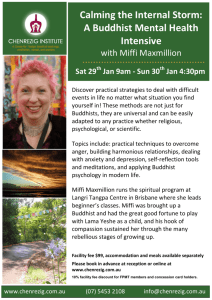

advertisement